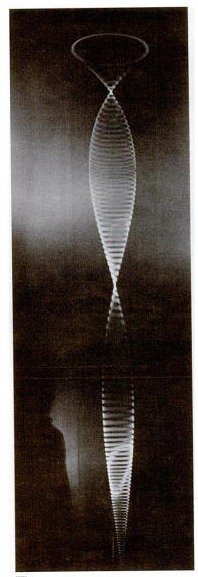

I came across a mention of Len Lye’s spectacular-looking kinetic sculpture a couple of weeks ago, while reading 1965 coverage of the Buffalo Festival of the Arts. Sandwiched in between a photo of Robert Morris and Yvonne Rainer in a nude dancing embrace and a headless mannequin dangling on the set of a Eugene Ionesco play was an installation shot of Lye’s Zebra at the Albright-Knox: “It consists of a nine-foot rope of fiber glass which, when set in swirling motion by a motor, bends into constantly changing shapes.”

Lye’s kinetic works had been getting some traction in New York–the Govett Brewster Gallery in his home country of New Zealand begins its sculpture section with Harmonic (1959), another spinning work similar to Zebra, which was shown at MoMA in 1961. But according to his biographer Roger Horrocks, the Buffalo exhibition and the concurrent solo show at Howard Wise Gallery in Manhattan were really his first chances to show multiple pieces at once.

Thanks to some steady evangelizing, some scholarship, technological advances that help realize–or keep running–his work, Lye has become something of a posthumous hero in New Zealand. There was a retrospective in Melbourne and New Plymouth NZ last year that included refabrications of several sculptures.

But Lye’s most frictionless path to history and fame is probably not his sculptures, but his films. He was probably the earliest practitioner of direct animation, drawing and scratching carefully synchronized abstractions and imagery onto celluloid as early as 1935, when Stan Brakhage was two years old.

Lye made A Colour Box as a pre-feature advertisement for the British General Postal Office. Other of his early animations were commercials, too. I’m so glad he did them, because they are awesome, but seriously, they seem like some of the most ineffective ads imaginable.

But as art and filmmaking, holy smokes. Just try, as you are mesmerized by all the separations and compositing and abstraction and color in Rainbow Dance, to remember that Lye made this in 1936:

He also made commercials using stop-action animation and puppetry, such as the rather incredible 1935 short for Shell, The Birth of the Robot, whose tiny kinetic figures and machines look like the missing link between Alexander Calder’s Circus and Ray and Charles Eames’s Solar Do-Nothing Machine:

It didn’t occur to me until just now, watching Trade Tattoo, a 1938 GPO short in which Lye incorporates both direct animation and coloring and found footage, but the saturated, post-production colors and the collage of abstraction and photo/film realism suddenly reminds me of Gilbert & George’s distinctive visual style.

I don’t know what WWII did to the GPO Film Unit’s output, but both Gilbert and George were born during the war, in the early 40s, and only George grew up in the UK. [Gilbert was born in Italy and moved to London to study.] Perhaps there was a Lye/GPO legacy lingering around St. Martins in the 60s. Or maybe it was all lava lamps and LSD. Who knows?

All of these YouTube clips, by the way, are from user BartConway, who turns out to be an OG filmsnob of the highest order, and thank heaven for it. He seems to be getting them from the BFI’s extraordinary-looking PAL DVD collection of works by the GPO Film Unit.

Skip to content

the making of, by greg allen