My list of incredible objects and machines from the past that need to be refabricated as art objects continues to grow.

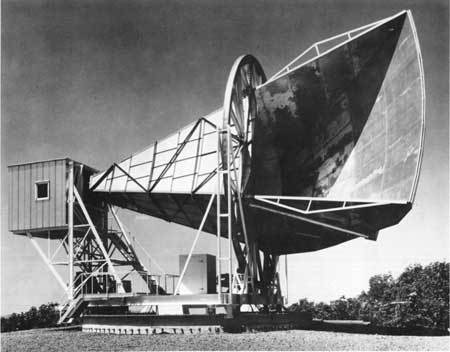

Actually, I guess the acoustic mirrors, built in the 1920s and early 30s as part of a sound ranging air defense network along the British coast, still exist, most spectacularly at Dungeness, above. So there’s really no need to rebuild them, only to preserve then. And admire them for their undeniable Serrawesomeness and Kapooriosity.

With the acoustic locators, however, the real question is where to start? Because, holy smokes, Dr. Seuss was basically a combat photographer.

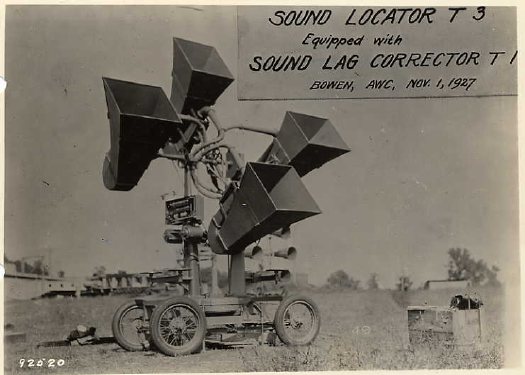

Do I go with the first one I saw, a US Signal Corps Exponential Sound Locator T-3 from 1927? Which looks an awful lot like the one Frank House patented in 1929, which was assigned to Sperry Gyroscope, the US’ leading manufacturer of anti-aircraft sound locators? Yet which was developed beginning in 1924 at Fort Monroe, VA? And which, even when its breakthrough “ear” designs appeared in the popular press in 1931, was still compared to “antiquated phonograph horns”?

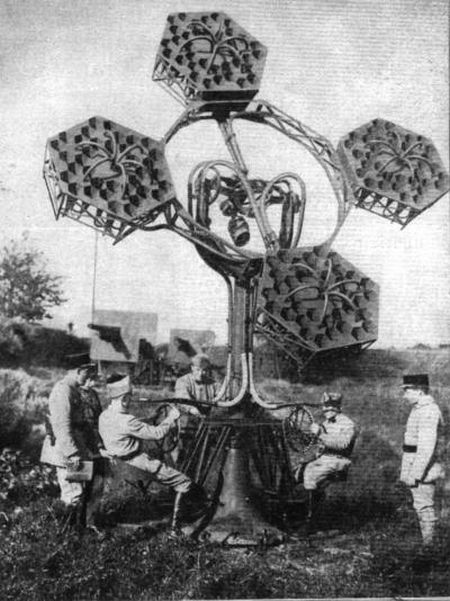

Or maybe go for decorative superlatives, such as the Hector Guimardian rarity of the télésitemètre designed by French Nobelist Jean-Baptiste Perrin? [via]

Or perhaps begin with a bit of the absurd, thanks to the Czech Mickey Mouse thing going on here? [via]

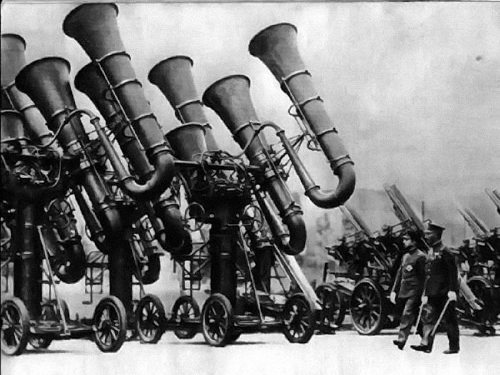

Frankly, the Japanese War Tuba is a little too Seussian Steampunk for even me to take it seriously, no offense to the emperor there. [via]

Surfing up information on these things, I’m well aware that I’m late to the sound locator game. But I didn’t think I was so far behind the Maker Faire/Burning Man crowd. Hmm. And hmmm.

Oh what the hell, maybe just throw this one on Governors Island and be done with it? The stethoscope to the stars.

But then there’s this highly portable German model–the awesome wheels and lowslung platform are typical among acoustic locators–which, wow. Stick your head in.

It’s like a real world precursor to other man-media interface devices, such as Walter Pichler’s Portable Living Room and Joep van Lieshout’s various fiberglass helmets, including the Orgone Helmet and the Sensory Deprivation Helmet [below].

Of course, it’s also a pretty short trip to a beer hat, so you gotta be careful.

Also of course, as a friend predicted when I started my giddy sound locator rant, it IS all about the satelloons. Specifically, the 50-foot horn-shaped radio antenna which Bell Labs used in Holmdel, New Jersey to track the epically faint radio signals reflected off of Echo IA’s mylar surface.

And which was later crucial to the inadvertent discovery of microwave background radiation, the first evidence of the Big Bang.

Earlier this morning, I tweeted half-seriously about the Bechers not working their way into The Original Copy, MoMA’s show about photography of sculpture. For all their conceptual sophistication, and their typological aestheticization to the industrial forms and structures they photographed, I don’t believe the Bechers saw their work in terms of, say, a readymade. Their art is their photos, not their subjects.

With their built-in obsolescence and anachronism, none of these objects could function as they originally did. Or were intended to do. And they don’t, really, remain as artifacts [except, as in the sound mirrors’ case, when they do]. So the only context in which they could plausibly exist–or credibly, since it’s plausible that they could be recreated by an enthusiast, a WWI re-enactor, or a nerded out…who is that guy in that refabricated sound locator, anyway?–is as an art object. And that’s the whole point, because they are these fantastic objects that surpass the presence and sophistication and beauty and…aura of so much intentional art, that it almost feels wrong not to appropriate or recontextualize or readymake them in somehow.

LATER THAT DAY UPDATE: Never mind. Going into my boxes, I see that, in fact, the title of the Bechers’ first book is Anonyme Skulpturen. Should’ve gotten the English edition after all. Stay tuned.

Yeah, well, in this 2000 interview with the Bechers, they talk about the beginnings of their work, which was considered “inartistic” by the art world of the day, the early 1960s. Bernd Becher: “To say, ‘This winding tower is an object, and it is just as interesting on its own terms’–that was not possible.” And then he talked about the urgency of photographing buildings they “didn’t like” which were slated for demolition, and explained not like them in terms of them not having “an aura.” So really, really, never mind.

Skip to content

the making of, by greg allen