God bless the Internet and all who surf upon her. A couple of weeks ago, I wrote about what I thought was an esoteric topic, even for greg.org: the fantastical lost machines from “Three Lessons of Architecture,” Daniel Libeskind’s exhibition at the 1986 Venice Architecture Biennale.

And yet, within hours of posting about them, I got an email from one of the guys who had been Libeskind’s grad student at Cranbrook and who had built and installed the machines. Hal Laessig is now artist/architect/developer in Newark, and he was gracious enough to share his stories from the “Three Lessons” project, and from Libeskind-era Cranbrook. They range from insightful to hilarious to outrageous, and I’m working on putting our interview together right now.

In the mean time, here’s a clarification about the references for the machine Laessig oversaw, the Writing Machine, which I had incorrectly described as being inspired by Raymond Roussel’s Reading Machine.

As it’s described here, at the very bottom of this ancient article on hypertext, the Reading Machine Roussel exhibited in 1937 was basically a book on a Rolodex. Color-coded tabs helped the reader navigate through multiple layers of cross-references and footnotes. Interesting, but nothing at all to do with the form of Libeskind’s version, which took its inspiration from somewhere else entirely.

Here’s Laessig on the origins of the Writing Machine:

I don’t think anyone knows this; it comes from Gulliver’s Travels. one of the lands that Gulliver goes to, they’re giving him a tour, and all the crops are in a shambles, why, because everyone’s at the university. And there was one professor who was having his students write an encyclopedia with a machine like ours.

It’s true, I couldn’t find any discussion of Swift, Gulliver, or the Grand Academy of Lagado, the floating island city Laessig’s referring to, in association with Libeskind. But now that he mentions it, let’s look at Libeskind’s own “Three Lessons” text again:

Since the Writing Machine (which is black and throws a gleam dedicated to Voltaire) processes both momory and reading material, it takes what is projected into an exact account. Not only the City itself (Palmanova) but all places written into the book of Culture are here collected and disposed.

Through an enlightened vision the random mosaic of knowledge is gathered together into seven times seven faces, each mirrored in a quadripartite realm. The totality of Architecture is shattered by the foursome reciprocity of earth, sky, mortals and gods and lies open to a contemporary stocktaking.

The four sides of the “Orphic” calculator or probability computer prognosticate the written destiny of Architecture whose oblivion is closely associated with Victor Hugo’s prophecy.

The four-sided cubes work in the following Swiftian manner:

Side 1: the City as a Star of Redemption is refracted and congeals into a “boogie-woogie” constellation.

Side 2: is a metallic reflection which shatters and disrupts the spatial-mathematical order of the 49×4 sides.

Side 3: consists of a geometric sign which points to a graphic omen or architectural horoscope.

Side 4: enumerates the forty-nine saints who accompany the detached pilgrim in order to care for this unerasable vulnerability.

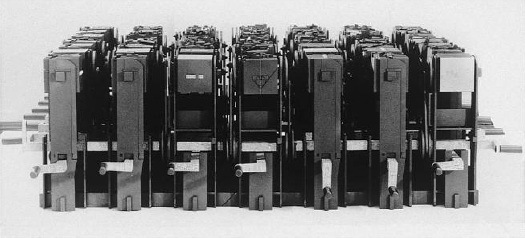

Thus the oppositions and complementary reciprocities which glide through the whole constitute a “destablilised technology” which would break up the mechanism instantly if the computerised controls (twenty-eight handles) weren’t there to keep it stable.

The Writing Machine is the first totally unstable text. As opposed to “stable” architectural texts which best fly in a straight line of myth and resist the pilot’s effort to climb, bank or dive, this “unstable” prototype is extremely agile – having no natural flight path.

It jumps around the text’s sky and is guided by an “active control system” which can perhaps never again disclose its starting position.

The Writing Machine is a contribution to Roussel scholarship. It links Africa and the Impressions of Italy through those miraculous figures whose presence is both inevitable and contingent. Angelica, with a grid, burnt on a grid: St Donatella; Mossem, killed by burning Iambic text onto forehead: St Theodore of Constantinople. By rotating the “foursome”, the arrangements appear ready for interpretation. These seemingly random relations are generated by an extremely sophisticated system which consists of 2,662 parts, most of them mobile. All are involved in an unpredictable rationalisation of place, name, person. Once in motion, the stockpiling and accounting of places, cities, types of buildings, gods, signs, saints, imaginary beings, forgotten realities, will present almost insurmountable difficulties for the operator, yet these are difficulties which can be eliminated through the revolutionary discipline of this turn towards a Buddhism of Action.

Whoa, what? There’s a lot rushing by there, including, if a namecheck for Swift.

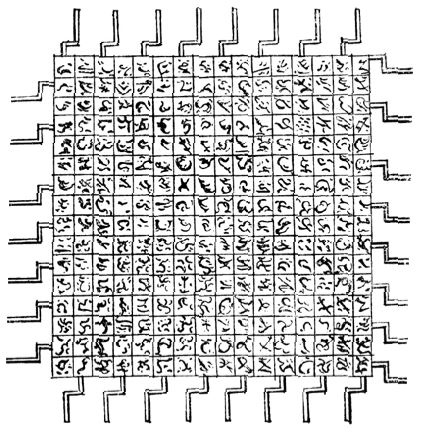

And the short answer is, yes: the fantasy machine Libeskind wanted to realize basically matches Jonathan Swift’s 1726 illustration of the automatic book-writing machine of the Grand Academy of Lagado.

The longer answer, of what it means, and what implications such a literary reference might have for Libeskind himself, as an architect/inventor, but also as an academic, are kind of awesome to contemplate.

For a quick Gulliver’s Travels refresher, the scene is from “Travels to Laputa,” where Gulliver visits the wing of the Grand Academy devoted to “speculative learning”:

The first professor I saw, was in a very large room, with forty pupils about him. After salutation, observing me to look earnestly upon a frame, which took up the greatest part of both the length and breadth of the room, he said, “Perhaps I might wonder to see him employed in a project for improving speculative knowledge, by practical and mechanical operations. But the world would soon be sensible of its usefulness; and he flattered himself, that a more noble, exalted thought never sprang in any other man’s head. Every one knew how laborious the usual method is of attaining to arts and sciences; whereas, by his contrivance, the most ignorant person, at a reasonable charge, and with a little bodily labour, might write books in philosophy, poetry, politics, laws, mathematics, and theology, without the least assistance from genius or study.” He then led me to the frame, about the sides, whereof all his pupils stood in ranks. It was twenty feet square, placed in the middle of the room. The superfices was composed of several bits of wood, about the bigness of a die, but some larger than others. They were all linked together by slender wires. These bits of wood were covered, on every square, with paper pasted on them; and on these papers were written all the words of their language, in their several moods, tenses, and declensions; but without any order. The professor then desired me “to observe; for he was going to set his engine at work.” The pupils, at his command, took each of them hold of an iron handle, whereof there were forty fixed round the edges of the frame; and giving them a sudden turn, the whole disposition of the words was entirely changed. He then commanded six-and-thirty of the lads, to read the several lines softly, as they appeared upon the frame; and where they found three or four words together that might make part of a sentence, they dictated to the four remaining boys, who were scribes. This work was repeated three or four times, and at every turn, the engine was so contrived, that the words shifted into new places, as the square bits of wood moved upside down.

Six hours a day the young students were employed in this labour; and the professor showed me several volumes in large folio, already collected, of broken sentences, which he intended to piece together, and out of those rich materials, to give the world a complete body of all arts and sciences; which, however, might be still improved, and much expedited, if the public would raise a fund for making and employing five hundred such frames in Lagado, and oblige the managers to contribute in common their several collections.

He assured me “that this invention had employed all his thoughts from his youth; that he had emptied the whole vocabulary into his frame, and made the strictest computation of the general proportion there is in books between the numbers of particles, nouns, and verbs, and other parts of speech.”

I made my humblest acknowledgment to this illustrious person, for his great communicativeness; and promised, “if ever I had the good fortune to return to my native country, that I would do him justice, as the sole inventor of this wonderful machine;” the form and contrivance of which I desired leave to delineate on paper, as in the figure here annexed. I told him, “although it were the custom of our learned in Europe to steal inventions from each other, who had thereby at least this advantage, that it became a controversy which was the right owner; yet I would take such caution, that he should have the honour entire, without a rival.”

But I still don’t know if that makes Libeskind Gulliver–or the professor?