Well this certainly wasn’t in his MoMA retrospective.

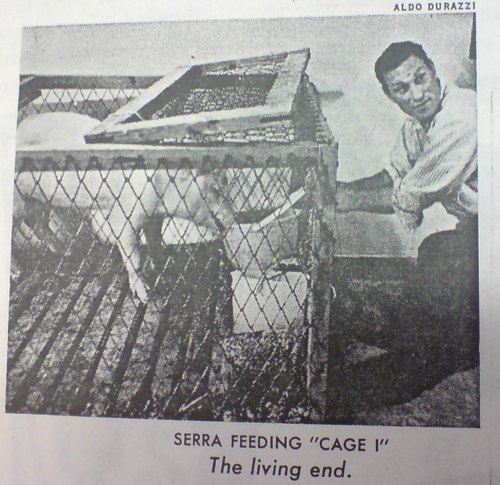

There are rubber and neon pieces dated from 1966-7, of course, and because they look prescient now, Benjamin Buchloh’s catalogue essay discusses early Richard Serra sculptures like Doors and Trough Pieces as “the official beginning of his oeuvre.” But Buchloh dismisses Richard Serra’s first solo show in May 1966 in Italy, where the young artist was traveling on a Fulbright, as nothing but “his rather literal responses to Rauschenberg’s combines.” Fortunately, the show got written up–with a picture, even–in Time Magazine:

Another realist of sorts also opened last week to grunts of approval in Rome’s Gallerie [sic] La Salita. He is Richard Serra, 27, whose credentials include a Master of Fine Arts degree from Yale and a Fulbright fellowship; he is currently deep in his zoo period. On exhibit were crude cages in which disport two turtles, two quail, a rabbit, a hen, two guinea pigs and a 97-lb sow. The big pig oinks away as part of a work called Live Pig Cage I. “I’m not saying the pig is art or is not art, says the artist, “but she makes a form.”

Other goodies on view include a stuffed ocelot, a stuffed owl and a stuffed boar (serra’s wife is an amateur taxidermist), bidets crammed with conch shells beaten-up boxing gloves, and broom bristles. Of his crass menageries, Serra says, “People didn’t know whether Robert Rauschenberg’s goat with a tire around it was art. Now they know. If an artist goes on making goats, though, he’s hung up.” Serra tries to stay loose and designs his works to last. Says he proudly, “I take great care to glue every feather down.”

Wow, so much going on there.

According to the only other [until now] Google mention of Live Pig Cage I, Merzbau.it’s history of Galleria La Salita [dead link updated to internet archive, 1/2022], Serra’s show was called “Animal Habitats: Live and Stuffed.” There’s another installation shot, and mention of a controversy over the unlicensed display of livestock, which the gallery owner Tomaso Gian Liverani ascribed to disgruntled competitors.

La Salita was not some art student co-op gallery, but one of the earliest champions of contemporary art in Rome. The gallery had exhibited Alberto Burri, Group Zero, Yves Klein, Gruppo T, and Christo. Liverani said that the livestock charges stemming from Serra’s show were dropped when the famous art critic Giulio Carlo Argan [who would later become the Mayor of Rome] and Palma Bucarelli, the director of the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, appeared as witnesses for the defense.

Maybe it’s convenient for Buchloh and other art historians to exclude Serra’s La Salita show from his oeuvre. It’s certainly easy because none of the work apparently survives, nor do reproductions, and the Museum Ludwig owns both Doors and Trough Pieces, as well as other very early work.

But Serra himself doesn’t exclude or disown it. In a 2006 Brooklyn Rail interview, he modestly explains to Phong Bui how, no, no, even if it might look that way, he probably did not start Arte Povera:

I dropped painting and started working with stuffed and live animals, including chickens, rabbits, and a live pig, zoological cage experiments, which led to my first one-man show in Rome at the Galleria La Salita. At that time, Arte Povera hadn’t really coalesced as a movement–I’m not saying I was responsible for it, but it was in the air. I think a year and a half later, Kounellis was showing live horses in a gallery, and the movement took off.

Serra went on to say the buzz from the Rome show made it to Venice, where he met his first US dealer, Dick Bellamy. And yet, however it has ended up that Serra’s first sculptures from his first exhibition are marginalized from his “oeuvre,” they sure sound central to someone else’s: his wife’s.

“Serra’s wife,” as Time called her, was not just “an amateur taxidermist”: she was an artist herself, a classmate of Serra’s at Yale, the late Nancy Graves. Here’s how her oeuvre got its start:

Nancy Graves’s personal aesthetic emerged in the later 1960s in the form of realistic life-size sculptures of camels. These works were rooted in her childhood memories of the animals preserved by taxidermists in the Natural History section of the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, Massachusetts and in the idioms of Abstract Expressionism taught at the Yale University School of Art where she was a student in the early 1960s. The interplay between the replication of nature and the formal values of abstract art was to inform her work throughout her life.

Now look at those pictures of the La Salita show again, where, as Merzbau put it, “Nature forcefully entered a work of art, with all its consequences…Something new was born.”

Mhmm.

When she showed her taxidermy-inspired Camels sculptures there in 1969, Graves was the first woman to have a solo show at the Whitney.

But she had made her first pair of camel sculptures in 1966, while traveling in Italy. They were destroyed.

First Rauschenberg & Johns, now Serra & Graves. Can I pick the artist couples who collaborate on their foundational work and then disappear it after separating in bitter acrimony or what?

Exhibitions | Please Don’t Feed The Sculpture (Time, June 10, 1966) [time.com]

La Salita, storia di una galleria [merzbau.it, google translation]