We’re consolidating storage spaces between New York and Washington, and it’s given me a chance to reorganize a bit. I found a couple of boxes my 1994 self apparently just threw stuff into, sealed up, and shipped off, almost like Warhol-style time capsules.

At least, that’s the positive spin on them. I’m sure Hoarders has a different take.

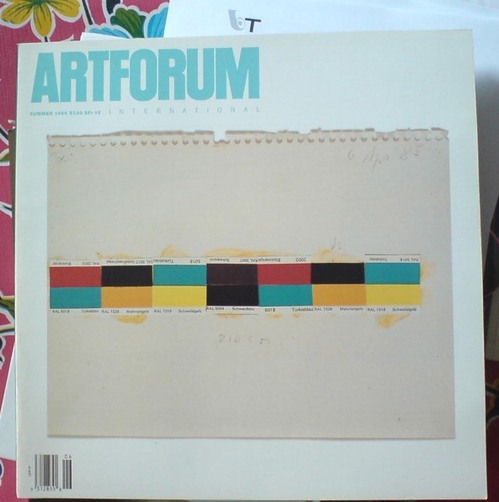

Anyway, one of the things I found was a stack of old Artforum magazines, including this one, from Summer 1994, which was something of a Donald Judd tribute issue. The cover image of a Judd study for a 1985 wall work collaged from paint chips jumped right out of the box at me.

The next thing I noticed when I picked it up was how thing and light it was: just 120 pages, plus a 32-page Bookforum inset. Adorable.

And then, flipping through it, I saw this:

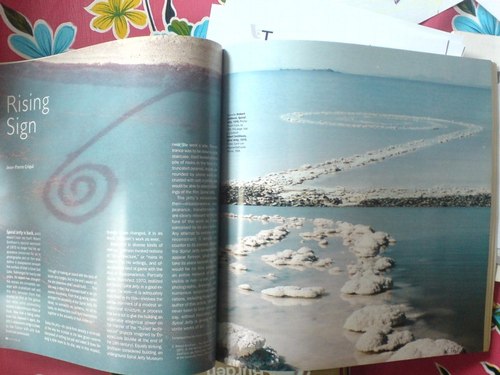

A two-page photospread, dropped into the issue in the Artforum equivalent of breaking news, which announced to the art world the re-emergence of Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty. Summer 1994, people, just like I said it did.

The 1993 aerial photo on the left is by Atsushi Fujie; it’s hard now to remember the time–even though it was most of the Jetty‘s first two decades of existence–when the only way to really see it was from the air. [Whoops, Fujie’s photo is dated here from the 1970s.]

In any case, the two contemporary photos on the right are by Carol van Wagoner of the Salt Lake Tribune, the paper which first published news of the Jetty‘s appearance in the Spring of 1994, before the snowmelt, when Great Salt Lake was at its low point.

The brief text by Parisian art historian Jean-Pierre Criqui, which opens “Spiral Jetty is back, and it doesn’t look like itself,” is a nice time capsule, suitable to mark the transition in the Jetty‘s history. The moment when the archetypal work of Land Art stopped being just a sign of itself–a concept, a state of mind, really–and reasserted its massive physical presence, and its inextricable link to its site:

The jetty’s vicissitudes, then–disappearance, reappearance, transformation–are clearly relevant to the nature of the work as it was conceived by its (co-) author. Any attempt to restore or to reconstruct it would run counter to its concept. Should the Spiral Jetty someday disappear forever, what would take its place beneath its title would be no less powerful: an entire network of signs, visible or not–a text, a film, photographs, drawings, and numerous subjective elaborations, including those of the author of this article, who has never been to Utah yet would say, without hesitation, that Spiral Jetty is among his favorite works of art.

As one who drove out to the Jetty for the first time that Summer, I can say without hesitation that it’s among my favorite works of art, too.