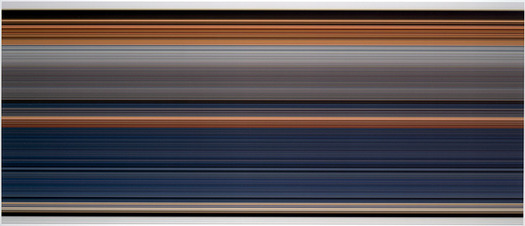

Gerhard Richter: Peinture 2010-2011, installation view, Marian Goodman Paris, image via

Yes, well.

While everyone is transfixed with Gerhard Richter’s c. 2009 on-camera squeegee technique, the artist himself has moved on to a schmear of the digital kind.

Gerhard Richter: Paintings 2010-2011 is on right now at Marian Goodman Paris, and most of the work on view barely seems to meet the promise of the show’s title. There is a large glass plate structure at the center of the gallery, and there are some small poured-paint-on-glass works. And then there’s the Strip series, unique digital prints mounted under Perspex.

To make Strip, Richter digitally mirrored/extruded vertical slices of an abstract painting–here, the description for the project’s artist book, Gerhard Richter: Patterns. Divided – Mirrored – Repeated explains it better:

The artist’s book documents Gerhard Richter’s experiment of taking an image of his original Abstract Painting [CR: 724-4] and dividing it vertically into strips: first 2, then 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024, 2048, up to 4096 strips. This process (twelve stages of division) results in 8190 strips, each of which is the height of the original image. With each stage of division the strips become progressively thinner (a strip of the 12th division is 0.08 mm). Endless more divisions are possible, but they would soon only become visible by enlargement. Each strip is then mirrored and repeated, which results in patterns. The number of repetitions increases with each stage of division in order to make patterns of consistent size.

Abstract Painting, CR:724-4, 1990, via gerhard-richter.com

The 520 page [!], EUR450 book documents 221 of these repeated patterns. Marian Goodman’s showing six. At first I expected the Strip works to be the same dimensions as 724-4 (92x126cm), but no, not at all; the Strips are much bigger, 160x300cm.

Buchloh is, as always, agog at the import and implications. An excerpt from a book-length essay as quoted in the gallery’s press release:

The status of painting in these new works is figured as exceptionally fragile, yet it is powerfully formulated in its assimilation to its technological challenges, as though painting was once again on the wane under the impact of technological innovations. Yet in its application of almost Duchampian strategies of fusing technology and extremely refined critical pictorial reflection, Richter’s astonishing new works open a new horizon of questions. These might concern the present functions of any pictorial project that does not want to operate in regression to painting’s past, but that wants to confront the destruction of painterly experiences with the very practice of painting as radical opposition to technology’s totalizing claims, and as manifest act of mourning the losses painting is served under the aegis of digital culture.

Mm-hmm. Richter has been working with photos of paintings and photos of overpainted photos for some time, so on the one hand, there is internal context for the artist’s pixel-width extrusions.

But the horizon of questions Richter’s new works open is only new if you’ve never left the studio. And how could painting, after all Richter’s work over all these years, still have it so rough? If we agree–and we have, cf., Liz Deschenes, Walead Beshty, Cory Arcangel, Tom Friedman (even), Andreas Gursky–that the aegis of painting has long since expanded in the digital culture, then can’t we welcome Richter to the party without pretending he threw it?

Tom Friedman, Untitled, 1998, image via metmuseum.org

Gerhard Richter: Peinture 2010-2011, through Nov. 3 [mariangoodman]

Same thing, documented work by work on the artist’s site [gerhard-richter]