Speaking of texts written in entirely unlikely places…

I really have no idea what to make of the kicker in Daniel Barnes’ Artslant review of the Brittania St installation of Damien Hirst: The Complete Spot Paintings:

As to be expected with Hirst, there is yet more spectacle. A member of Gagosian staff tells me that the key paintings which correlate specific colours with letters of the alphabet are the start of a game: if you look at each painting carefully, a sequence of colours will reveal a hidden word, and if you get the word first you win a spot painting.

I mean, first, second, and third: W, T and F? [Or in Morse Code, ⚈ – – – ⚈⚈-⚈?]

image via tate modern, © Damien Hirst. All rights reserved, DACS 2009

A secret word embedded in each painting? Is there one word repeated or 1,200 or 1,500 separate words? Is there one key for all of them, or one for each of them? Is there one free painting for each of them? If you crack the Hirst Code, do you become overnight the artist’s single largest collector, the Mugrabis of Hirst? If so, doesn’t Viktor Pinchuk already have a team of ex-KGB cryptographers working on this problem?

Entirely aside from the “win a painting” sweepstakes element–the Secret Hirst’s Other Spot Challenge–what are the conceptual contours of a Hirst Code? Are the words encoded in The Complete Spot Paintings random, or a list, or do they constitute a single, secret text? Is it an essay, a manifesto? An epic poem or sacred text? Is it the first page of a great novel,, or did Hirst randomly encode a page from his pharmaceuticals catalogue–or from a Tesco mailing, or his cable bill, whatever he had lying around the studio? Or does it just say ARSE 1,500 times?

With a secondhand, anonymous gallerina anecdote relayed by a “critic/philosopher” whose forthcoming book, The Art of Spectacle, “offers an analysis of the work of Damien Hirst at the level of aesthetics, meaning and ideology in order to defend him as the greatest of contemporary artists,” we’re either one factcheck away from a cross-eyed prank, or one murderous albino monk away from a worldwide conspiratorial phenomenon that could turn Tate Modern into a Wonka-fied Louvre this spring.

I guess it’s to Hirst’s credit that I wouldn’t put either scenario past him. Hirst revealing that his 25-year-long series of conceptualist abstract painting is actually a pedantic word jumble as it is as easy to imagine as Hirst alluding to a secret message in the spots when there is none. Or at least none that he put in. Yet. How long would it take a series the artist describes as endless and infinite to produce meaning? If a million monkeys typing a million years can come up with Shakespeare, surely Hirst’s assistants can manage to produce a color-coded word or two by now, just a few million dots in?

How different, really, is the Hirst Code’s supposed promise, that ” if you look at each painting carefully, a sequence of colours will reveal a hidden word,” from the esoteric intellectual constructs of academic art criticism and theory? While PhDs argue over the epistemological implications of Baudrillardian spectacle, and Marxists decry the triumph of neoliberal luxury capitalism, a mum from Brixton sitting down with her colored pencils each Sunday slowly pieces together A-R-S-E-N-A-L D-I-A-Z-E-P-A-M B-O-L-L-O-C-K-S. Do these potential interpretations have to be mutually exclusive?

Explicitly encoded meaning and symbolism is nothing new to art, and throughout his career, Hirst has beaten the allegorical references to death, at least, to death.

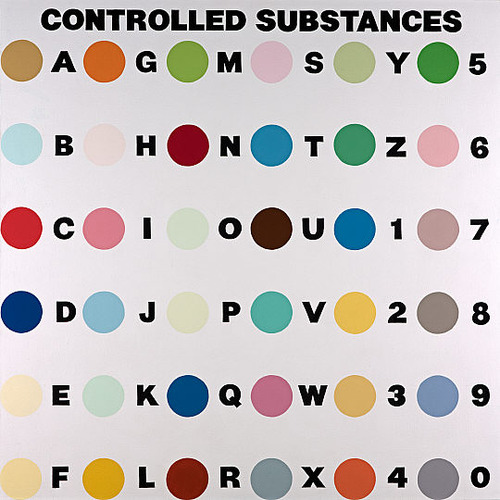

Even without Barnes’ claim, and even if Hirst himself hadn’t created a “key” painting in 1994 [Controlled Substances, top, given to Tate and the National Galleries of Scotland by Anthony d’Offay], the spot paintings practically compel a viewer’s visual search for meaning. As Jenn Bostic described it, that seeming potential for meaning exists among the spots, and across the system of production itself:

Being a graphic designer, I was most interested in the paintings with the greatest density of dots, placed on a grid. I found myself looking at them like text pages in a book — but in a new language of Pantone dingbats. That perhaps somehow hidden within the colors, there is a legend you can break. Evidently the colors are non-repeating, which I believe and am impressed by (anyone who has ever dealt with custom color mixing knows that 25,000 individual colors is a recipe for pain and heartbreak). Harder to believe is the notion that the colors are also placed at random. But when I stepped back and allowed the dots to become a halftone, the overall effect was an even, all-over field. I saw what typographers call ‘rivers’ and ‘canyons’. These are the fractures that run through carelessly set justified typography (that, unsurprisingly, look like rivers and canyons). But, these ‘rivers’ were surprisingly minor. And I didn’t see any dark or light clusters; No islands or holes — the sort of true randomness I’d expect. Instead what I saw were paintings that reflected a great deal of careful design.

Apparently careful design, but also not behaving like a text.

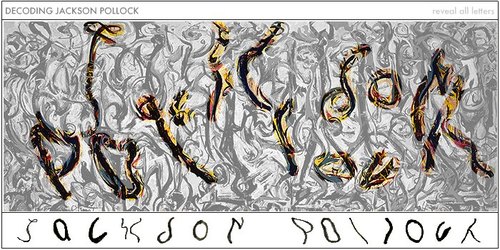

Mural (1943) analyzed by Henry Adams in “Decoding Jackson Pollock,” Smithsonian, 2009

A Hirst Code–or the search or assertion of one, even–would be one more incarnation of a defining dynamic of modernism: abstraction’s perennial battle with representation for hearts and minds–and eyeballs. From over a century now, folks have been trying to tie abstraction back to whatever “reality” it was abstracted from.

Sometimes it’s overt, like van Doesburg’s cows and Mondrian’s landscapes. It can be imagined, like seeing Brancusi heads in photos of reflections on a Canadian lake. It’s seeing–or at least holding in your mind–a desert lanscape in a Clyfford Still. And it’s arguing that actually Pollock’s canvases are contain the residue of the images he painted in the air. Or that one of his breakthrough all-over murals is actually an abstract obscuring of the artist’s own name [above].

Richter’s color charts are readymade abstractions, documentary depictions or mimicries of manufacturers’ sample cards. Even seemingly “pure” abstraction, like Ellsworth Kelly’s color and form, turn out to be based on, referenced to, observed natural phenomena: the curve of a leaf, the shadow out a Parisian bus window.

Is it a joke, and if so, who is it on, if Hirst’s diffidently meaningless, subjectless, intentionless spots turn out to be gorgeously produced steganography? Does it matter terribly if there is a message–“the” message–embedded in the paintings and we don’t decode it? Is our interest or enjoyment of a Dutch still life dependent on knowing the Protestant symbology for each fruit and lobster in it? Does it change our understanding of Johns’ Map when we know that his visible collage scraps include a history of orgies?

That last example has direct bearing on the possibility of a Hirst Code. As recently as 2007, the most august art historians said Johns’ collages were made of unknowable detritus from his studio floor. But I found the exact page of Johns’ orgies book in seconds using Google. In the 60s, Leo Steinberg joked about the thousands of dissertations that would be written by generations of scholars painstakingly identifying and interpreting the source imagery in Robert Rauschenberg’s collages. Those impenetrable secrets can be matched up in seconds now with a computer script.

Assuming it’s there, whatever code Hirst devised for his spot paintings almost certainly predates the Web and networked computing. Controlled Substances was 1994. SETI@Home, one of the first groundbreaking distributed data analysis systems, where screensavers searched the static of the universe for an extraterrestrial radio signal, launched in 1999. If no one’s cracked the Hirst Code yet, it’s only because no one’s tried.

So what would it take to decipher the Hirst Code, besides an algorithm and some computing capacity? Did you need to complete the Spot Challenge, and if you completed it without looking for the Code, did you miss the much bigger prize? You’d need a robust dictionary of words generic, proper, and branded, which you can winnow down to a more manageable size by eliminating anything that repeats a letter. And to automatically match the key’s spot colors to the rest would require a clean, complete, calibrated dataset, one which accommodates the miniscule differences among the [tens of] thousands of unique hues. Because those lookalikes could really mess you up.

And this is why I am even more skeptical of the Hirst Code than when I first heard of it. Because such a dataset exists, or soon will. And so whatever else it might be, the Hirst Code is an extraordinary gimmick The Complete Spot Paintings: 1986-2011to sell his new book.

Pre-order The Complete Spot Paintings: 1986-2011 via amazon, $176 [amazon]