Untitled (for Parkett), 1994 image via phillips de pury

I’ve been wondering how Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ billboard edition, Untitled (for Parkett) was playing out in the real world. How many of the 84+15+? copies still existed? How many had been installed? Installed and destroyed? Have any been installed and preserved after its permanent site traded hands? Or are most/all of them like mine, still sitting in the box, rolled up, and “incomplete,” waiting? Waiting for what? The perfect wall in the house you’ll never leave? The market to rise too high to ignore?

Untitled (for Parkett), 1994 image via christie’s

What I already knew: seven examples of Untitled (for Parkett) have come up for auction, the first in 2000, and at least three of them didn’t sell, including one example that was missing its certificate. The sales prices, $4,000, $10,000, £6,600, are pretty low in the Felixian scheme of things. More importantly, though, they’re low in relation to real estate, even to high-end wallcovering; if someone were to install the billboard, and then sold the space where it resided, the market value alone–or in combination with the reassurance that eh, whatever, there are a hundred more–is not enough to aid its preservation.

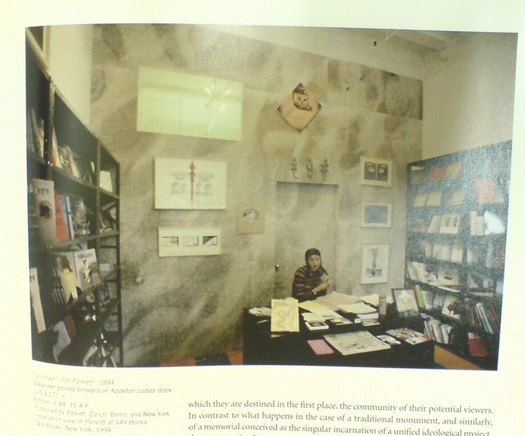

Installation shot, 149 Books, 1994, image via julie ault’s felix gonzalez-torres

Untitled (for Parkett), then is almost doomed by its own nature to exist in a state of fungible incompleteness, or worthless realization, or inevitable destruction. Any billboards that do get installed permanently somewhere will only exist until the paper fades, or the loft is sold, or the kitchen gets remodeled. And then it’ll be gone.

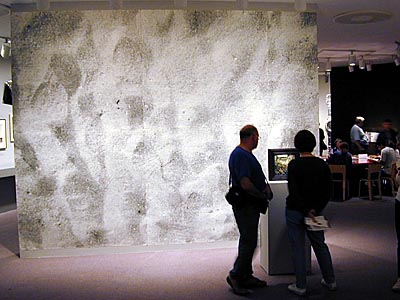

installation view, London, 2001, all images from here on via parkett

I contacted both the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation and Parkett. Allison Hemler, the Foundation’s Director of Archives and Communications did some investigating, and found very little information indeed. There are almost no records of the status of the 84+15 editions, with the exception of #19, which was permanently installedat the Art Gallery of South Australia in Adelaide. [Interestingly, it’s not listed in the collection database, though another Felix piece is. It’s apparently been included in three exhibitions between 1998 and 2009. I’ve emailed the Gallery for any information or images, but haven’t heard back. UPDATE: And a spokesperson told me the work was not in the 2009 show, and is not installed, but is “in the Gallery’s works on paper archive.” So. So I guess there are no known permanent installations of the work right now, despite those being, of course, the only kind.]

installation view, MoMA, 2001

The “several exhibition copies” mentioned in the catalogue raisonne turns out to be just four. Triumph Productions, the Manhattan outdoor advertising printer which created the original 8-panel silk screen is still going strong, but neither the Foundation nor the Estate before it has ever reprinted Untitled (for Parkett) for exhibition, and there are currently no practices in place for doing so.

installation view, dublin, 2002

So unlike many, even most, of Gonzalez-Torres’ other works, which are endlessly reproducible and renewable, Untitled (for Parkett) has a finite and dwindling existence. Unless it is installed and preserved in those sites. Which is possible. A billboard preservation network could emerge. These mostly private spaces could become the sites of public pilgrimage. Assuming they were ever private to begin with. From a 1991 interview with Bob Nickas:

Someone’s agenda has been enacted to define “public” and “private.” We’re really talking about private property because there is no private space anymore. Our intimate desires, fantasies, and dreams are ruled and intercepted by the public sphere.

installation view, venice, 2003

Though it has apparently never been written about specifically, Untitled (for Parkett) is mostly seen in reproduction, and in exhibitions. The Foundation’s exhibition history lists 14 shows, including eight exhibitions where it’s not clear if the billboard was shown, or just illustrated: three were at commercial galleries, one was organized by the Sammlung Goetz, and two were at museums. In addition to the three shows in Adelaide which included a single print, the billboard was installed in six exhibitions. I’d add a seventh, the 1997 Whitney Biennial; I remember it installed in the lobby, with the curtain of light strings, Untitled (America), hanging in front of it.

installation view, 2010, singapore

But three of the six shows, including the debut exhibition in 1994, one at MoMA in 2001, and another in 2010 at Singapore’s Tyler Print Institute, are Parkett collection shows. Parkett’s ever-growing collection of artist editions is basically on constant world tour. It’s traveled to at least seven additional venues. Their installation images are interlaced throughout this post in reverse chronological order. They show that billboard at every venue. And why not? Besides the Jeff Koons balloon toy, it’s one of their most ambitious, awesome editions.

Here’s the complete [I think] list: 149 Books, New York (1994); Louisiana Museum, Denmark (1996); MAK Center, Los Angeles (1997); London (2001); MoMA, NY (2001); Dublin (2002); Venice (2003); Kanazawa, Japan (2009); Singapore (2010); Seoul (2011). Ten installations, almost every one with different dimensions and site specific quirks, which should make reinstalling a single exhibition print impossible [as well as unauthorized].

So is Parkett churning through actual numbered editions? The A.P.’s? An undeclared stack of exhibition copies? They haven’t gotten back to me, so I don’t know. But that’s 15 installations total.

Felix did discuss the edition, , or an early conception of it, anyway, with Joseph Kosuth in 1993:

JK: This goes from the earlier idea of the collector as someone who buys knickknacks to the idea of the collector as patron. It’s a certain kind of leap that has more tod o with intellectual engagement and less to do with reducing art to nice little things in the apartment.

FGT: You know, someone once asked me to make an edition of prints. But I thought, why make an edition, why make a print? The world doesn’t need any more prints by artists. So I said no. But then I thought about it, and I said, well, why don’t we push the limits and do a billboard? The conditions are such that you can only show it in public. You have to show it in public.

Obviously, he decided to push the limit in a different direction. When Kosuth lauded his embrace and tweak of a “traditional form” and context, Gonzalez-Torres responded:

Well, my first reaction was a very predictable Leftist reaction which more and more I am questioning and finding very static and self-defeating. At this point I do not want to be outside the structure of power, I do not want to be the opposition, the alternative. Alternative to what? To power? No. I want to have power. It’s effective in terms of change. I want to be like a virus that belongs to the institution. All the ideological apparatuses are, in other words, replicating themselves, because that’s the way the culture works. So if I function as a virus, an imposter, an infiltrator, I will always replicate myself together with those institutions. And I think that maybe I’m embracing those institutions which before I would have rejected. Money and capitalism are powers that are here to stay, at least for the moment. It’s within those structures that change can and will take place. My embrace is a strategy related to my initial rejection.

I can’t tell if the market-based capitalist system is failing to realize Untitled (for Parkett), or succeeding in preserving it, in bulk, unrealized and incomplete, for the future–or both. But it is certain that Felix has successfully infiltrated Parkett, which is busy replicating his work together with their institution.