Now, I see it’s been out there for at least 40 years–and it’s right there in a book on my shelf from just a few years ago–but I did not know that Laszlo Moholy-Nagy did not actually phone in his Telephone Paintings. Or that someone says he didn’t.

The account I’ve always heard is the artist’s own, written in 1944:

In 1922 I ordered by telephone from a sign factory five paintings in porcelain enamel. I had the factory’s color chart before me and I sketched my paintings on graph paper. At the other end of the telephone, the factory supervisor had the same kind of paper divided in to squares. He took down the dictated shapes in the correct position. (It was like playing chess by correspondence.)

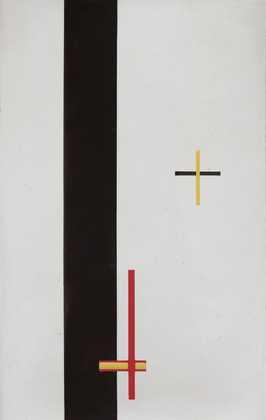

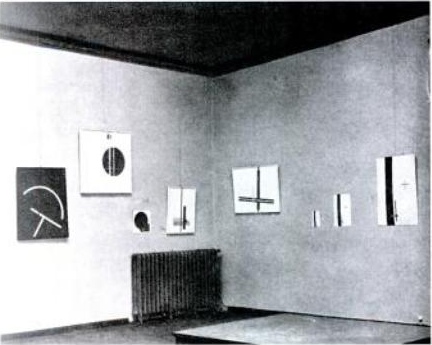

MoMA has two of these five paintings, Construction in Enamel 2 and 3. They were given to the museum by Philip Johnson in 1971. The paintings are identical except for the dimensions; EM 2 is 48x30cm, and EM 3 is a quarter the size, 24x15cm. EM 1 is, in turn 4x bigger, 96x45cm. They were exhibited together in 1924 at the Sturm Gallery in Berlin, while Moholy was at the Bauhaus. I don’t think there was an EM 4 or an EM 5, though. Or maybe I’ll have to add them to my missing paintings list.

But Johnson gave the two paintings to the Modern in memory of his friend, architecture critic Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, who was the artist’s second wife. It was his first wife, Lucia Moholy, who was with him when he made the enamel paintings, who cast doubt on the phone story. In a 1972 book, Margin Notes: Documentary Absurdities, Lucia tried to counter the embrace of the Telephone Pictures by the Minimalist, Conceptualist, and Systems Art movements by insisting that he didn’t actually call anyone; he went down to the sign shop and placed an order. Which was so easy, she said he said, “I even could have done it by telephone.” Could have.

Which seems like it’d matter. Was the geometric composition of the painting really just so simple that, 20 years, one rise of Nazism, one divorce, one remarriage and one escape to the US to set up a new Bauhaus later, Moholy decided to embellish the mediated, distancing, telephonic aspects of the work? And who’d fact check such a thing, right? Oh, right.

Or maybe it doesn’t really matter. That’s what Brigid Doherty argues in the catalogue for MoMA’s 2009 Bauhaus exhibition. Doherty cites a 1924 statement about the Sturm Gallery show:

One can have works of this sort manufactured on demand on the basis of the Ostwald color charts and a scaled grid. One can therefore even order them by telephone.

Can. What’s important about these enamels is that Moholy could have used a phone, not whether he actually did; that the information needed to execute them was not visual. They represented a switch from–as Moholy wrote about in 1920, in an essay titled “Production Reproduction”–reproduction of a given image to instruction- and data-based production.

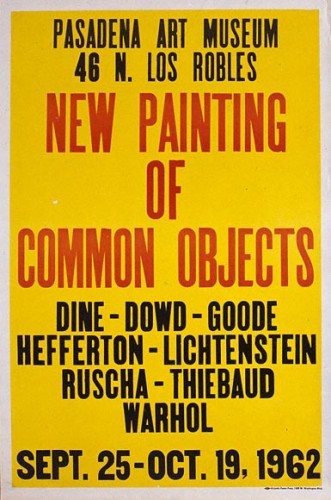

Which, I guess my point is, I had no idea about any of this. At least I’m not alone. If Lucia’s corrective didn’t surface until 1972, and no one could question the august Bauhaus leader/refugee’s own account, if only because the artist died in 1946, a year before his “I called” story was published, everyone took it as face value. And now I wonder just how true the other phone-it-in stories are out there: like Walter Hopps’ anecdote of Ruscha ordering the New Painting of Common Objects poster over the phone. And Judd’s whole Bernstein Bros. creation myth, [which Michelle Kuo called “largely false”].