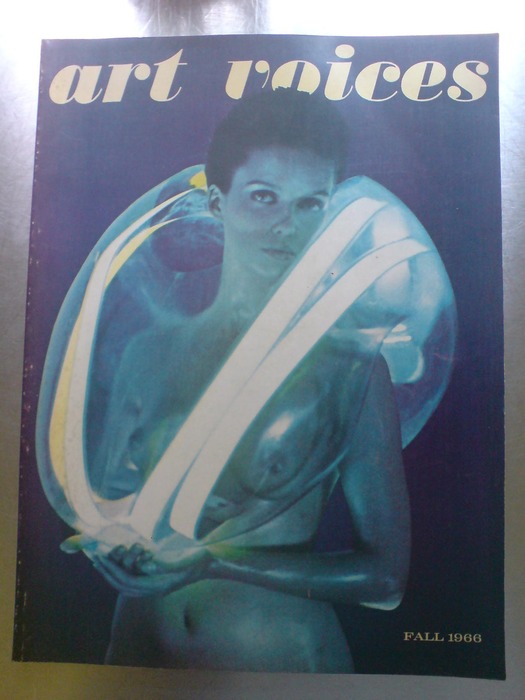

Well look what I unearthed while reorganizing my books in storage. The Fall 1966 issue of Art Voices, a short-lived magazine that, I swear, I bought for the articles.

Seriously. It’s the issue where Robert Smithson & Mel Bochner published “The Domain Of The Great Bear,” their photo-essay/article-as-art expedition through the Hayden Planetarium. I mean, sure, you could read it in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, but don’t you want to see it printed slightly bigger?

Anyway, in the short features section up front, right before Lawrence Alloway’s essay on early space age films, is this awesome story by pioneering downtown journalist Walter Bowart about a secret, artist-run tattoo parlor called Apocalyptic Tattoo. It’s not turning up online anywhere, so I’m putting the whole, short, thing after the jump:

Apocalyptic Tattoo

The Skin-Art as Art (A Long and Noble History)

Walter Bowart

Tattooing is banned in New York State because, the judge said, “the decoration, so called of the human body by tattoo designs is in our culture a barbaric survival, often associated with a morbid or abnormal personality.”

Should the painter Francis Bacon turn his hand to the skin-art this statement might hold true, but it seems to be just another utterance of the mediocrity-rule of our courts.

Tattooing has a long and noble history. It originated before recorded history and probably was one of man’s first efforts at distinguishing himself from the rest of the animal kingdom. Examples of tattooing have been discovered in excavations dating back to 12,000 B.C., though they were done by means of cutting, branding and scarring in ornamental shapes.

Tattoos by puncture (gold needle and shark tooth) was first practiced in Egypt. Mummies dating from the years 4000 B.C.-2000 B.C. contain tattooed skins. During the Third and Fourth Dynasties, Egypt was in communication with Crete, Persia, Greece and Arabia, and was most likely instrumental in spreading tattooing as far as China.

Later tattooing caught on in Japan. The Japanese transformed the Chinese ritual into a purely ornamental form of a very high degree. The style and technique of the Japanese tattooists (horis) cannot be matched anywhere else in the world then or now. The Japanese tattoos are of an almost three-dimensional appearance, have delicate coloring and are done one puncture at a time with bamboo needles.

It was the Polynesians who were responsible for spreading the tattoo art to our modern culture, though tattooing was practiced in the Americas among the Mayans, Aztecs, Peruvians and Incas, while the Danes, Saxons and Norsemen brought sophisticated tattooing to Britain.

The modern Western tradition of tattooing started when Captain Cook brought tattooed “savages” back to England from his Polynesian voyages and put them on exhibition. At the same time, Cook’s sailors were coming back from the mysterious new world sporting original work by the Polynesian artists. A fad developed and really got rolling when King Edward VII was tattooed in Jerusalem in 1862.

In 1914, Samuel O’Reilly invented the Electric Vibratory machine, which allowed the first relatively painless three-needle tattoo. This machine was later improved and equipped to handle up to eleven needles by Professor George Burchett, the British “King of Tattooists.” This machine, which is still used, consists of a small brass box with precision electrical movement, mounted on a metal tube which contains a bar to which eleven vibrating needles are soldered. The outfit is rigged to a transformer and rheostat and is controlled by a foot pedal. The needles are dipped into organic dyes which the machine deposits under the skin at a rate of three thousand punctures per minute only 1/32nd of an inch deep. Because of the extreme rapidity of the machine’s operation, its handling requires an expert artist to control the delicate line.

Like anything that has been banned, tattooing is undergoing an illicit revival. A couple of Lower East Side painters, who prefer to remain anonymous, have transferred some of their mandalic designs to acetate, and from there to skin in twenty colors.

tattoo photo by Walter Bradel via Art Voices

A modern-day witches’ covenant in Houston, Texas requires that all the members have tattooed identification designs, such as ankhs and hex signs, describing their powers and rank among the witches. Astrology buffs are getting their zodiac signs done in four colors. And one Lower East Side painter has an anatomical drawing of a heart tattooed over the area where the real one is hidden.

In Manhattan an avant-garde tattoo studio is set up in a cold-water flat. It has no sign or phone, and the only way to get tattooed is to know a friend of the artist. It’s called “Apocalyptic Tattoo and is run by two young artists as an artistic endeavor rather than for any commercial motive.

Though these modern skin artists are primarily concerned with new designs, they are historians of the tattoo. Their studio is lined with photographs of traditional designs from Africa, Micronesia and different periods of the Western tradition. Are Nouveau designs are abundant at the Apocalyptic studio as well as religious mandalic signs.

The process is simple. The tattoo first designed on paper is transferred to an acetate stencil 1/2,000th of an inch thick. The area to be tattooed is shaved, swabbed with alcohol, and vaseline is applied. Medical charcoal powdered through the stencil sticks to the vaseline on the form of the design, and the outline is followed by the liner needle making the rapid, shallow punctures. Next the colors are put in with a shading needle, and the total area is rinsed with alcohol and bandaged.

The tattoo may take from ten minutes to an hour, depending on the intricacy of the design. But an hour’s sitting is enough for all but the toughest patron. Though the process is not painful, soreness does develop, limiting the length of a session.

Strict health measures must be followed. All equipment is medically sterilized, and precausions are taken against infection and hepatitis–the two real enemies of bad tattooing.

The artists at Apocalyptic Tattoo say” Unlike most American tattoo artists, we would like to work in chiaroscuro and with hard needles such as are used in Japan, where tattooing has reached its height. We’d like to find our way to a common symbolism of body adornment, and bring tattooing to occupy its rightful place as an art form.

“Tattooing is practiced with an eye to an effect and ears tuned to a message which Judges cannot hear. Skin art is practically painless and takes little time to accomplish, thanks to O’Reilly’s electric tool.

“Simple sterilizing procedures insure against infection in a wound which barely breaks the skin. The licensing of tattoists would easily disqualify those who were ignorant of hygienic method. Although they won’t admit it, tattooing is being kept illegal because the Board of Health would rather not hire a couple more inspectors to cover tattooing in the city. To date Apocalyptic Tattoo has yet to be confronted by a perverse or morbid request.”

Art Voices, Fall 1966, pp. 19-20.

I guess that was a bit longer than I thought. Unfortunately, Mr. Bowart passed away in 2007, but perhaps someone else knows the identities of the artists of Apocalyptic Tattoo.