Speaking of Cady Noland,

I’m kind of fascinated by the recently decided set of lawsuits surrounding the withdrawal of Noland’s 1990 work, Cowboys Milking, from a Sotheby’s contemporary day sale in November 2011. Noland had disowned the work under the Visual Arts Rights Act.

When the first suits were filed by the artwork’s consignor, dealer Marc Jancou, against both Sotheby’s and the artist herself, it was not quite clear what the problem had been, though Jancou was clear in his public sentiment that he’d been hurt, to the tune of $6 million, and distraught for 20 million more dollars. It came out in a flurry of countersuits that Noland considered the work damaged, but that was in dispute, too.

But as is often the case, a dive into the filings and documents proves both informative and entertaining. [As a NY state, not federal, court case, all the documents are available for free online. Just search the NY State Unified Courts e-filing System as a guest for Index no. 650316/2012. Don’t think of the endless stream of unlabeled, repeat documents as a slog, but as a legal literary fugue.]

Basically, in April 2011 Jancou [who, btw, I know, and have bought work from in the past] bought back Cowboys Milking from a collector he’d sold it to earlier. Then he turned around and consigned it to Sotheby’s for their Fall sale. It was featured very prominently in the catalogue, and its estimate was $250-350,000. [Jancou’s invoice was submitted as evidence; he paid just over $100,000 for it. He even got a $1,000 knocked off, apparently to cover some conservation work the piece needed. Which turns out to be the central issue.]

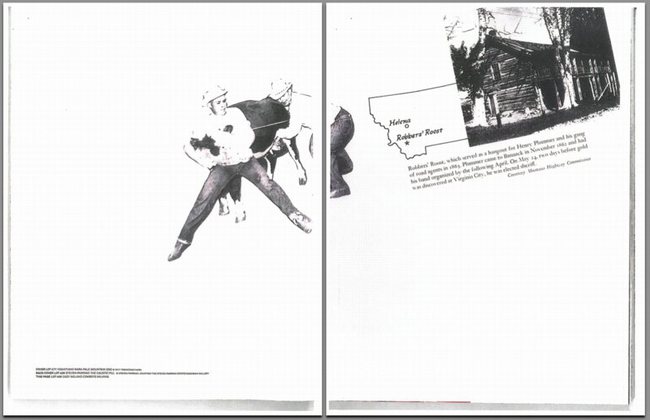

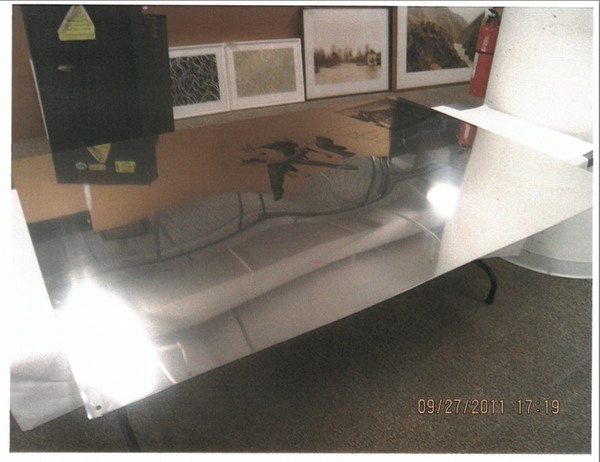

Cowboys Milking is a unique silkscreen on a very thin, highly polished sheet of aluminum 4-ft high and 6-ft wide. Holes are drilled into each corner for hanging. The scale of the image and the material make reproductions of it difficult, disorienting, or misleading. [Sotheby’s 2-page spread, above, summarily crops the image to hide a nail hole.] This intake documentation image by Sotheby’s gives the best sense of what it actually is:

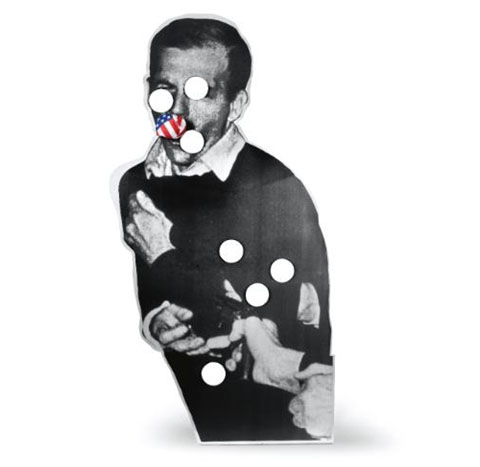

When the works went on public view [there were two other Nolands, including Oozewald and Bloody Mess, both 1989, in the November evening sale] the artist went to Sotheby’s to inspect them, and via her attorney, promptly instructed the auction house to withdraw Cowboys Milking, because it “differed materially” from its original state. Federal and NY state law both grant an artist the right to disown an altered, damaged or mutilated work, and to prevent her name from being associated with it, and that’s just what happened, right before the sale.

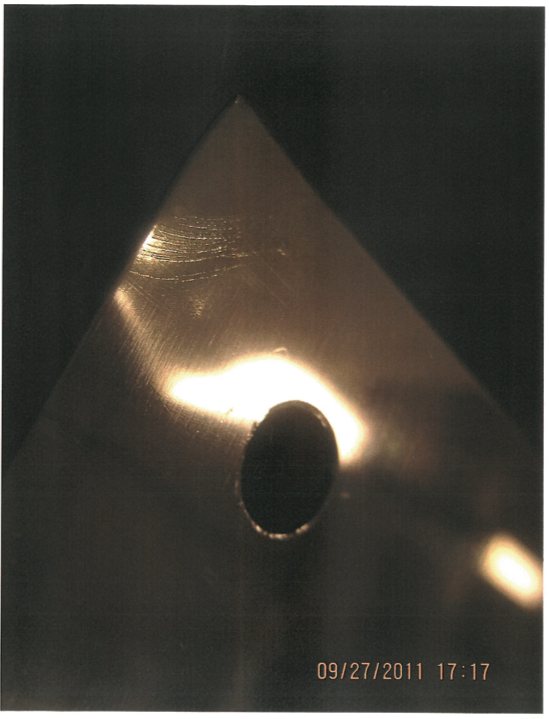

Sotheby’s condition report declared the work to be “in very good condition overall,” with “light evidence of wear” in the corners and “a crimp in the upper right corner and another to the lower left corner.” They didn’t yet know that these were the result of conservation efforts by the Noland expert Jancou had engaged, who had found the 1/16-in. thick mirrored aluminum to be an unforgiving material. When she saw them, Noland deemed the repairs unacceptable. And ultimately, that was that. As the final arbiter of her work, and the work that’s traded under her name, if Noland rejected it, it really didn’t matter that Jancou or Sotheby’s or even the conservator thought that the wear on the edges was fine, or normal. It was a dealbreaker.

Detail from Sotheby’s intake inspection, a crimp, apparently.

When Jancou found out, he was pissed, though in those early days, the dispute linked the work’s condition to its “authenticity.” In an extraordinary email to his Sotheby’s rep, he wrote,

this is not serious!

why does an auction house ask the advise [sic] of an artist that has no gallery representation and has a biased and radical approach to the art market?

Which prompted internal Sotheby’s email discussion:

Got it. I would say that when the artist, through her lawyer, has questioned the authenticity of works and has threatened to go public with her grievances that we have to take it seriously Would he prefer if we are forced to withdraw it due to potential authenticity issues? Or reading about it in artforum that its [sic] damaged to the point she no longer considers it her work?

By the time he filed his suit, and after Oozewald had sold for a world record $6.6 million and his work hadn’t, Jancou called out the auction house and the artist for inconsistent treatment. Cowboys Milking got pulled for just a couple of insignificant dings, he argued, while Oozewald was cleared to sell, even though it was missing its base. But, which, no.

Oozewald, 1989, ed. of 4, image sotheby’s via artnet

For the other two works for sale, Noland insisted the auctioneers certify that every item in Bloody Mess was accounted for and scattered in its precise spot; and that they include a notice that Oozewald had a mismatched base, and that the artist would provide the buyer with a properly fabricated replacement. These conditions met, the artist permitted these works to be sold using her name. This is not biased or radical market behavior.

Though you’ve gotta admit, it does seem kind of harsh. Was it really necessary to completely disown the work? Noland’s responses to both Sotheby’s and to Jancou’s lawsuit reveal there was more to the story. Turns out the previous owner of Cowboys Milking had already tried to sell it–through Christie’s–and Noland had already inspected it, and deemed it too different and damaged, and had insisted on its withdrawal. Jancou’s purchase came just days after this unpublicized rejection by the artist. Sotheby’s basically accused Jancou of covering up this rejection when he brought the work for sale, a charge the dealer strenuously denied.

[I have no direct knowledge myself, but it’d seem to me that if he really had not been told about the Christie’s rejection, Jancou would have a very solid claim against the work’s owner, and the ronin curator who put the deal together. Yet he’s apparently let these guys off the hook. It makes one wonder. But anyway.]

From Noland’s perspective, it’s all the same. The work she already officially disassociated herself from pops right back up, whack-a-mole-style, a few months later, with evidence of an unsatisfying restoration.

In exerting her prerogative under the Visual Artists Rights Act, Noland’s lawyers sought to prevent anyone, but, seemingly, especially Jancou the work’s current owner, from associating the artist’s name with it in any way, especially in his efforts to sell it. Paradoxically, the legal response also puts any question of the work’s “authenticity” to rest, because in order to assert VARA rights, Noland needed to first authoritatively claim sole authorship of the work.

I’m really going on too long now, but besides the textual and soap operatic elements of the lawsuits themselves, I am now fascinated by the implications of Noland’s affirmative negation of Cowboys Milking, both for the real world/art world it inhabits, and for the object which, for two-plus decades, had been an artwork.

Did anyone who bought, sold, handled, or saw Cowboys Milking over the years expect that its status was dependent on perfectly preserving and protecting its corners and surface? Such care is certainly possible, and art works typically get it in relation to their rarity and fragility, but most of all, to their value. It costs much more and takes much more effort to care for a fragile work, especially of this scale. This luxury commodity decorating your home, which had been cool and edgy, now becomes a burden, if not a menace, threatening to erase your entire investment in it unless you change your life around it. It becomes an instrument of control, infiltrating some of America’s finest homes, and operated remotely by the artist herself.

People talk about Cady Noland’s abandonment of the art world and art making, but this Sotheby’s case shows exactly the opposite: she only has rejected Jancou’s expectations of “gallery representation” and production- & sales-driven discourse, in order to operate entirely on her own terms. She remains highly involved in the presentation of her work, and as the objects she made travel around the world, she engages with them anew, creating new meaning and context.

With the Cowboys Milking decision, every Noland artwork has been imbued with the ominous potential of its own demise. Where they once dreamed of cashing in on their 90s prescience, every owner of a Noland is now reflecting on that time they bumped it with a vacuum, or wishing they’d sprung for the good crate after all. Am I the only one who could totally imagine such an encounter being in total harmony with the bleak degradation and dystopian decline that Noland’s work was ostensibly, originally “about”? By introducing this precarity through the sacrifice of Cowboys Milking, Noland has updated her artworks’ operating system for 2011.

But what of this particular 4×6′ aluminum sheet? What’s to become of it? If an artwork is whatever an artist says it is, then Noland has created the opposite. This is an object an artist has definitively declared is not art. That seems kind of amazing. By testifying to her creation of it, and then disassociating herself from it completely, Noland and Cowboys Milking are now inseparable. Through this rejection, Noland seems to have succeeded in making the holy grail of 1960s/70s artist idealism: a work that cannot be consumed and commodified by the evil market.

Or did she? Is dissociation really the end? Discussing her use of different metals with Michele Cone, Noland once said, “The coolness might infer dissociation, but the mirror effect in some places is to draw you back in after the dissociation.”

Oozewald and Publyck recreated for Cady Noland Approximately

In 2006, Triple Candie staged a controversial retrospective of unauthorized copies of Noland sculptures based on published images and descriptions. None was for sale. But with the disposition of this lawsuit, the exact opposite now seems possible: couldn’t Cowboys Milking remain in the market the way Old Masters do, without attribution? As the work of, say, School Of SoHo, or The Cowboys Milking Master [Mistress]. No one would ever need to claim Noland was connected to the work–thanks to the lawsuit, everyone would already know.

Or maybe Jancou could just keep it, live with it, enjoy it in the comfort of his own home, a beautiful, shiny reminder of the importance of buying art for love, not as an investment. And when guests ask who made it, he can smile and demur, “If you don’t know, I can’t tell you.”