What you need is a system. To keep you going, to avoid artist’s block, to keep the pipeline filled.

I think Lewitt’s cubes were less a system than an idiom. Flavin’s fluorescent tubes, too.

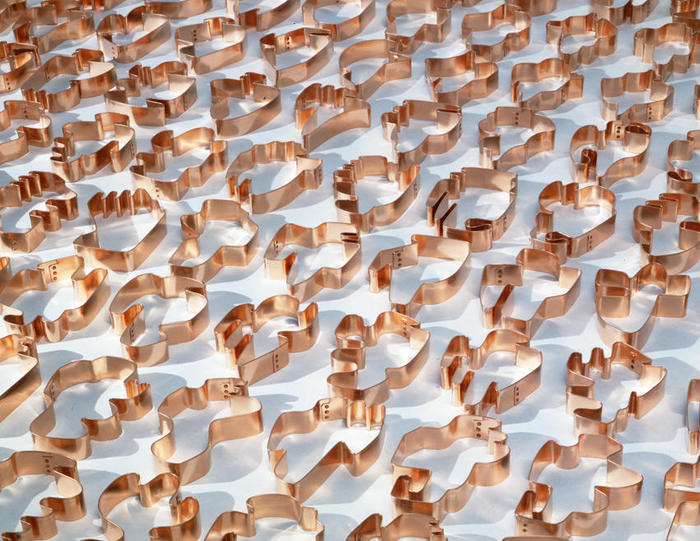

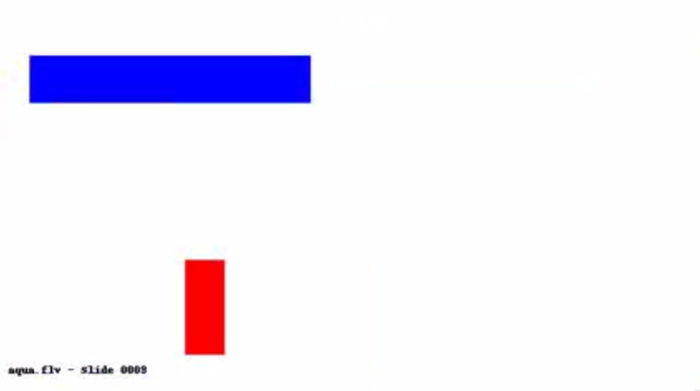

Shapes from Maine, 2009, image: petzel.com

Allan McCollum’s got a few systems going. Systems are his medium. Define some parameters, calculate the total set, start producing, and don’t stop till you–or your market–drops. The Shapes Project, started in 2005, has 31 billion possible permutations, enough for everyone ever to be born on earth to have one. Personally, I’m largely unmoved by McCollum’s results, but I respect their jawdropping systemic integrity.

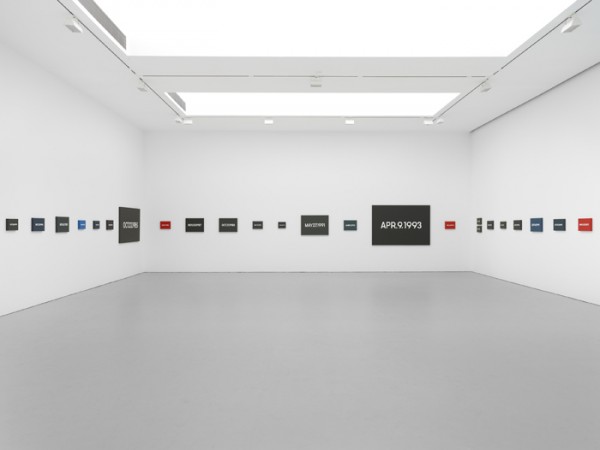

But On Kawara’s Today Series, now that’s a system I can get behind. It’s a bonus when your system is conceptually tight, also when it can carry you out of this world.

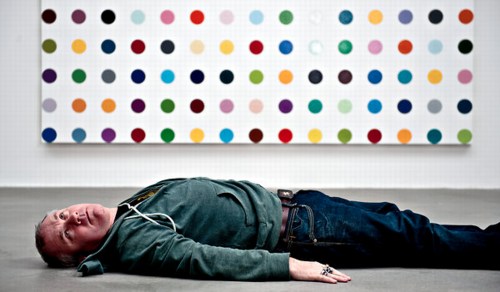

As that Kawara link above mentions, Hirst’s spots are also a system, which operates autonomously and, he’s even hinted, which could continue posthumously. [Kawara’s date paintings and Hirst’s spots were up in NYC at the same time in 2012, and Karen Rosenberg said one series was about time, and the other was about money. I love that.]

Anyway, you want to make sure you don’t get trapped by your system. Flavin had a helluva time with that, especially towards the end. So keep enough irons in the fire, throw a system or two into the merchandise mix. Like Richter’s new Strip paintings; he’ll be able to pull those off the printer till the very last. And he could leave the print queue open in his will, even. [I wish him all the continued health and happiness and look forward to seeing his show at the Beyeler.]

One would want a system to be ambitious, to stake a large claim, but to be doable, sustainable, saleable over the course of its realization. When Bruce High Quality Foundation announced their project to recreate all 17,000 objects in the Metropolitan Museum’s antiquities collection in Play-Doh, it seemed daunting. I guess you could say they’ll probably have product available as long as they’re able to keep selling.

Danh Vo, We The People, 2014 installation at Brooklyn Bridge Park, Public Art Fund, image: James Ewing

Danh Vo’s We The People project to recreate the Statue of Liberty as 250 separate panels, meanwhile, has a finite end, even though the ridiculously awesome scale of the project seems impossible. On a purely physical object level, this has to be one of my favorite art undertakings ever, a confluence of abstraction & representation, metaphor & literalism, presence & absence. As soon as I get to Vo’s pieces on view in City Hall Park and Brooklyn, I’ll try to write more about it.

From Kawara [solo] to Hirst [factory] to McCollum [vector files] and Richter [digital] we can see a diminishment of the artist’s hand in inverse proportion with the expansion in scope, approaching capitalist nirvana, an industrial-scale infinity.

This is all nice and terribly important, but it’s also prelude to what might be the most ambitious readymade art generation system ever, which I’m totally calling dibs on: Webdriver Torso.

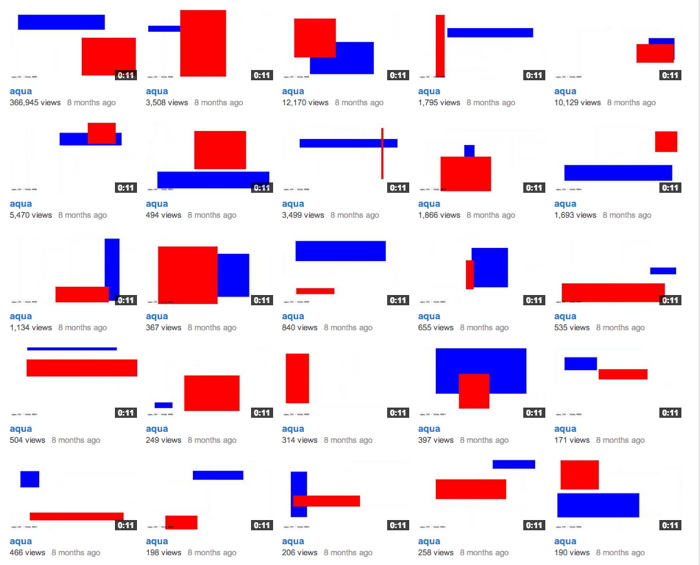

Webdriver Torso is the largest of at least four related YouTube accounts which have been uploading randomly generated videos [the pace is currently two videos ever 8-12 minutes] since mid-2013. Webdriver Torso has nearly 80,000 videos now; on all four accounts there are more than 130,000 videos total. Webdriver Torso’s channel now has more than 38,000 subscribers. Where a few weeks ago, almost all the videos had zero views, or maybe one, now videos of seemingly nothing immediately get several dozen views. [The other channels still have mostly zero views.]

Since being discovered and publicized a few months ago, various websites have speculated on the purpose and origin of Webdriver Torso, calling it an alien communications tool, or a crypto-spy numbers station, or a test channel for some video software developer. The most persuasive explanation I’ve seen so far is Italian blogger Paolo B.’s theory that the Webdriver channels are connected with a YouTube uploader development initiative for 3D videos or multiple videos, run out of Google’s Zurich office.

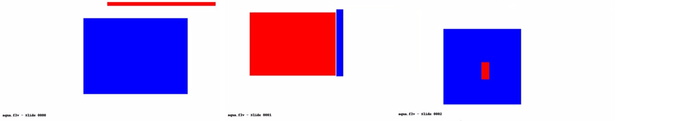

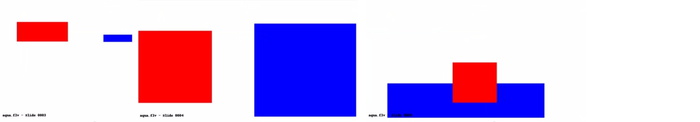

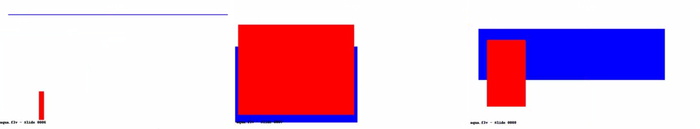

Each video is eleven seconds long and contains ten slides, each with a composition of blue and red quadrilaterals. That’s 1.3 million possible compositions, with more being added at an average rate of one every six seconds. And they all look more or less like a Malevich, or Lazslo Moholy-Nagy’s Telephone Paintings.

So obviously turn them into paintings. It seems impractical to sort through all the videos, looking for some “best” composition. Better to stay true to Webdriver Torso’s random nature, and grab a few. Or even grab one and use it [all], make nine paintings at a crack. Or maybe use the slides in the most recently uploaded file from the moment you make a sale, or the moment you place the order with Chinese Paint Mill. Then it becomes an indelible, but meaningless, marker, an index of its own creation. Like On Kawara’s date paintings, they can be made in various sizes. Maybe you get a giant hard edge monster to anchor an important wall. Or maybe you get a smaller, complete set and grid them up, a la Olafur.

A web storefront that offers paintings in only the compositions from the last few minutes of uploads wouldn’t just reward quick purchase decisions: it would demand it. Out with this fair-wandering nonsense of, “Oh put it on hold for me, I’ll let you know.” and in with Buy It Now. Of course, what’ll happen is that someone will sit there and hit refresh all day, in eternal hope that the next batch of nine will have the Webdriver Torso Mona Lisa in it. [Just a second, gotta check Twitter.]

Ooh, tmpK89znn, which just went up, has some really nice ones in it:

Let’s see how those turn out.

A timeline of Webdriver Torso [botpoet via @soulellis]

the truth about Webdriver Torso [ventunosu21]

Skip to content

the making of, by greg allen