Yet, in a way, abstract art tries to be an object which we can equate with the private feelings of the artist, the canvas being the arena on which these private feelings are acted out. Warhol presents objects which, in a sense, we can equate with public, communal feelings…In a way [Warhol’s works] might be said to objectify experience, turn feelings into things so we can deal with them.

Gene Swenson, unpublished draft, 1964 via sichel/oup

It’s awesome to hear about the experiences of people other than me who are now living with Facsimile Objects. I’m glad to know it’s not just me who finds them interesting.

Lately I’ve been thinking about them as objects, trying to explore the implications of the term and format I adopted semi-ironically from Gerhard Richter, who used it to explain the unsigned stacks of giclée on aluminum reproductions of paintings he began authorizing for museums as fundraising editions. [As their numbers and critical acceptance have grown, Richter has since classified them under the less obscure and/or more market-friendly term “prints.”]

Warhol was not on my mind, then, but like learning a new word and suddenly hearing it everywhere, I am now hypersensitized to any mention of objects or objecthood. And to asking, “But what does it MEAN [about MEEE]?”

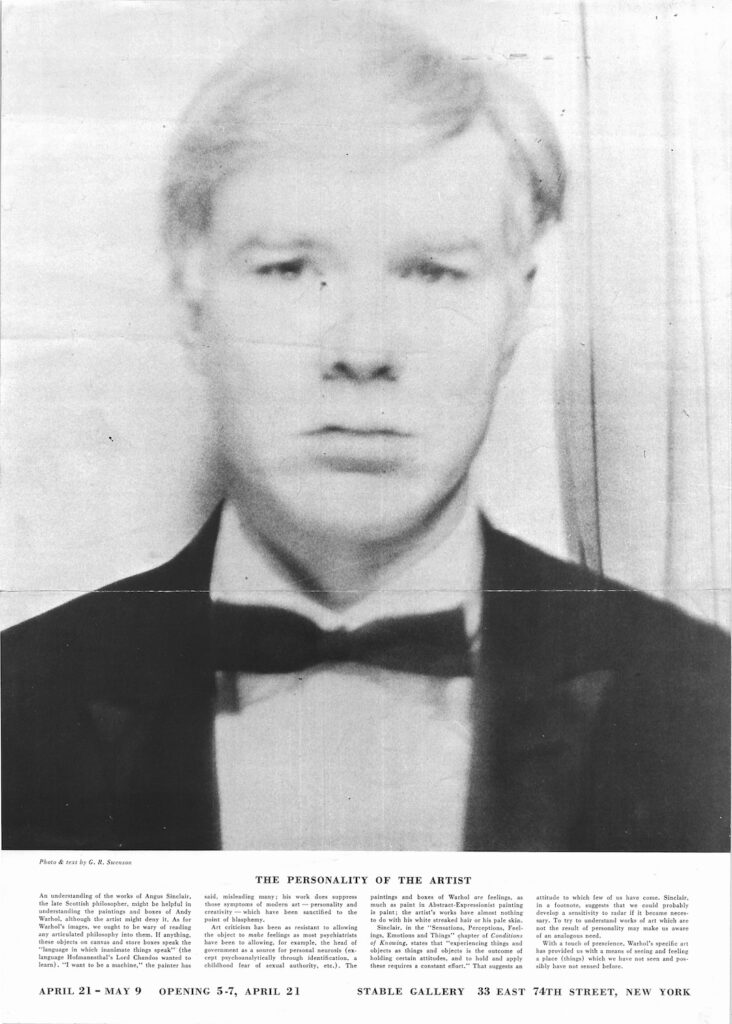

Thus the pullquote up top, which comes from an unpublished of critic Gene Swenson’s flyer for Andy Warhol’s second show at Stable Gallery, the Brillo Box show, from April–May 1964. It is illustrated in Jennifer Sichel’s utterly fascinating 2018 paper, “Do you think Pop Art’s Queer?” Sichel reveals that Swenson’s 1963 interview of Warhol for the ARTNews series, “What is POP Art?” which became a foundation of decades of critical understanding of Warhol and Pop, was heavily edited to remove any mention of homosexuality. And that, in fact, Warhol and Swenson talked extensively, even primarily, about Pop’s relationship to homosexuality as a counter to the machonormativity of Abstract Expressionism. Here is Swenson’s short, published text in full.

The Personality of the Artist

An understanding of hte works of Angus Sinclair, the late Scottish philosopher, might be helpful in understanding the paintings and boxes of Andy Warhol, although the artist might deny it. As for Warhol’s images, we ought to be wary of reading any articulated philosophy into them. If anything, these objects on canvas and store boxes “speak the language in which inanimate things speak” (the language Hofmannsthal’s Lord Chandos wanted to learn). “I want to be a machine, the painter has said, misleading many; his work does suppress those symptoms of modern art–personality and creativity–which have been sanctified to the point of blasphemy.

Art criticism has been as resistant to allowing the object to make feelings as most psychiatrists have been to allowing, for example, the head of government as a source for personal neurosis (except psychoanalytically through identification, childhood fear of sexual authority, etc.). The paintings and boxes of Warhol are feelings, as much as paint in Abstract-Expressionist painting is paint; the artist’s works have almost nothing to do with his white streaked hair or his pale skin.

Sinclair, in the “Sensations, Perceptions, Feelings, Emotions and Things” chapter of Conditions of Knowing, states that “experiencing things and objects as things and objects is the outcome of holding certain attitudes, and to hold and apply these requires a constant effort.” That suggests an attitude to which few of us have come. Sinclair, in a footnote, suggests that we could probably develop a sensitivity to radar if it becomes necessary. To try to understand works of art which are not the result of personality may make us aware of an analogous need.

With a touch of presience, Warhol’s specific art has provided us with a means of seeing and feeling a place (things) which we have not seen and possibly not sensed before.