The Estate of Minerva Teichert is suing The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints twice, in two federal courts, for ownership and control of dozens of religious and pioneer-themed paintings by the artist, which have been on display in chapels, temples, church museums, and historic sites, for decades. Though she found some success in the 1930s and ’40s, Teichert, who studied with Robert Henri, did not gain a significant reputation until after her death in 1976. She is now considered one of the most important artists in Mormon culture, and certainly the most prominent woman. [It feels like irreconcilable folly, bringing terms like Mormon culture and prominent woman together, but here we are. I am fine, though, saying Teichert was the best Mormon painter in the Church’s history.]

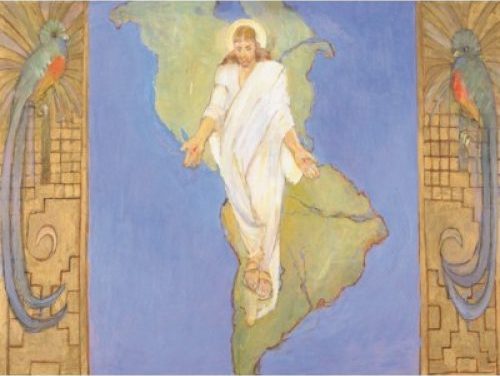

The first lawsuit, filed in Wyoming in 2021 and set to go to jury trial later this year, demands the return of four paintings which hung in the chapel in Cokesville, Wyoming, where the artist lived and worshiped most of her life. One painting [above?] was moved to the newly built Star Valley Temple in 2014, and the other three were removed in the Spring of 2020, at the beginning of the pandemic, when church meetings were suspended and buildings were left unattended for months. The paintings were all replaced with full-scale giclée copies.

The second lawsuit, filed on January 30, in California, also pursues ownership claims of these four Cokesville paintings, plus dozens more. In this case the Estate claims that an oral agreement was entered in 1955 with the local Cokesville bishop by which Teichert loaned her paintings for display in the chapel, and that they would be returned to the family if they were ever deinstalled or moved.

The basis for ownership of the rest of the paintings is not clear, except that the Estate registered copyrights for 31 paintings—including, oddly, only three of the four Cokesville paintings—in 2021. The estate itself was constituted as a legal entity in 2018 with Tim Teichert, a grandson of the artist, as its representative. Minerva Teichert died in 1976, and her husband Herman died in 1982, both intestate.

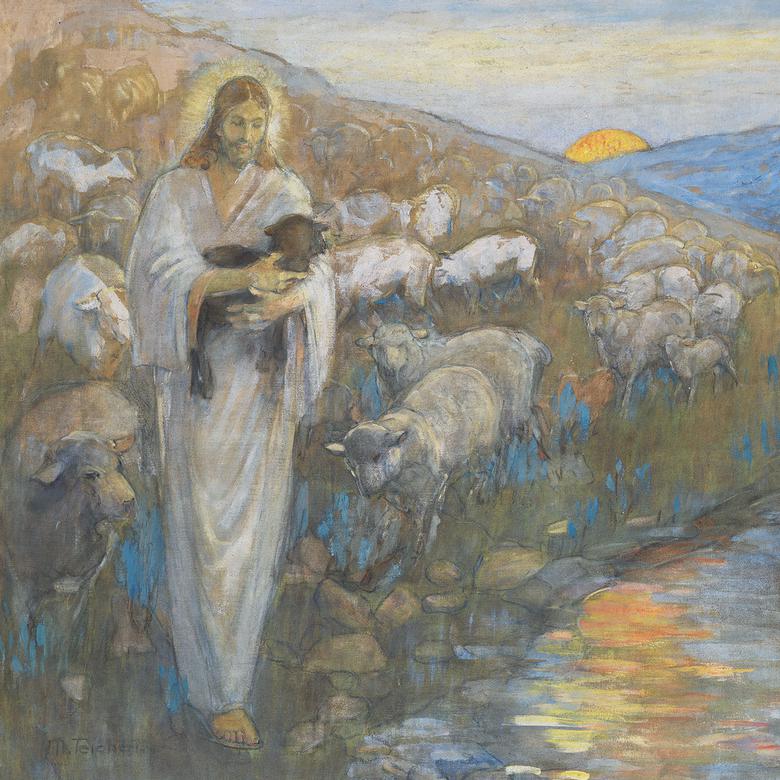

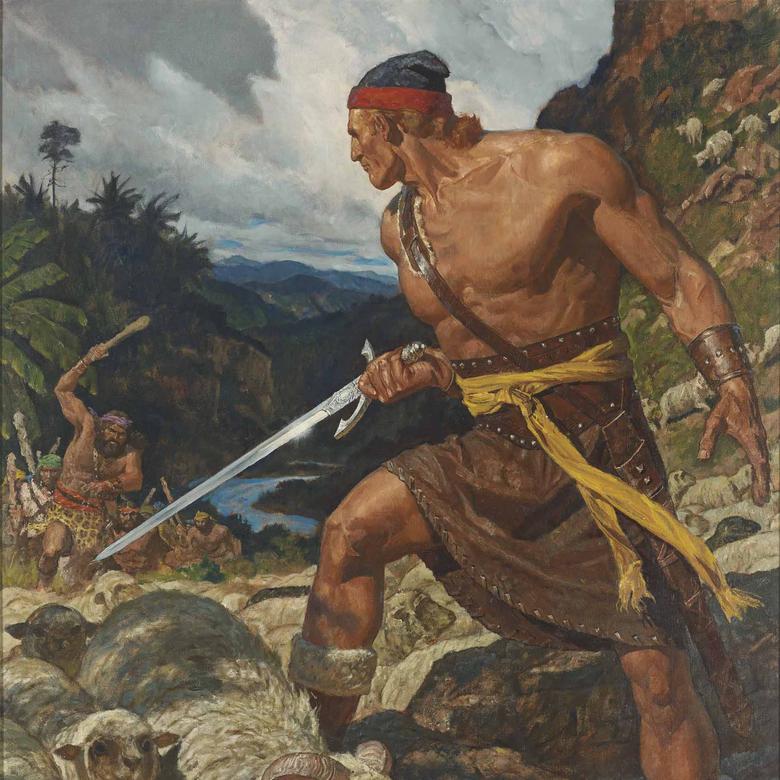

The 2023 lawsuit also targets the LDS Church-owned Brigham Young University, its museum of art, and the Church-owned bookstore and publishing concern, all of which are accused of copyright infringement for selling print reproductions of this particular subset of the Teichert paintings the Church has had in its possession for decades. The Brigham Young University Museum of Art holds at least 92 paintings and 67 works on paper by Teichert, including 11 large paintings donated in 2012,and at least 43 paintings made between 1949-51 for an illustrated version of The Book of Mormon.

[Though she had just completed an entire mural cycle in the renovated Manti Temple, the Church rejected the paintings. At the same moment, the Church’s children’s magazine commissioned Cecil B. DeMille’s concept artist, Arnold Friberg to make a series of muscly paintings, which were later added to The Book of Mormon. Some years later, Teichert ended up trading her works to BYU in exchange for tuition for her descendants and some Cokeville neighbors.] Another of Teichert’s grandchildren, Marian Eastwood Wardle, is curator at the BYU Museum and a leading figure in reviving the artist’s posthumous reputation.

Teichert sold, donated and gave away hundreds of paintings. After her Salt Lake City dealer’s death, and with her work out of official Church fashion, Teichert painted gifts, including depictions of funeral flowers for grieving neighbors. In the decades since her death, the reputation and financial value of her paintings has increased substantially. The Church has been a/the major force in showing, promoting, and using Teichert’s work, and has certainly acted as if they owned the paintings in their possession. But they’re not the only ones. Prints of Teichert’s paintings are offered for sale widely in Mormon marketplaces IRL and online.

The use of specious 2021 copyrights to claw back both licensing rights and revenues, but also physical ownership of paintings themselves, for works made 70, 80, even 100 years ago, seems like an uphill climb at best. If they were all declared public domain tomorrow, it still feels unsatisfactory for the Church to exert outsize control over Teichert’s legacy, with no recourse for her descendants. That said, the timing and scope of these lawsuits end up feeling like a money grab. In 2012, there was talk of turning Teichert’s Cokeville ranch—inhabited at the time by a grandson, though it’s not clear which one—into a museum. Maybe somewhere along the way, the discussion could move from the swamp of intellectual property to the firmer ground of real estate, and the Teichert’s could have their reward.