On Tuesday, September 9, 2014, The Metropolitan Museum of Art enacted what historian Daniel J. Boorstin called a pseudo-event. It was intended to draw public attention to David Koch, a right-wing extremist whose inherited fossil fuel fortune funds a vast network of politicians, judges, lobbyists, and ideologues that has pursued power in its own service for decades.

A small fraction of his wealth, $65 million, was used to redo the plaza in front of the Met, where Koch was a trustee. The main feature is a pair of large, square, fountains of black granite, with circles of choreographed water jets. The fountains are ringed by a rough cut black granite seating ledge that bears the inscription, David H. Koch Plaza, in gilt letters.

In 2017 I made a work of an endless, collaborative performance of negation, where the Met’s millions of visitors and passersby, New Yorkers and outsiders alike, continuously sit in a way that blocks this aggrandizing, carved text from view. That piece is called Untitled (Koch Block), and it is still in process. Please join it whenever you’re nearby.

But there is another work, a predecessor, unearthed only recently, through a search for something else, I already forget what. On the 9th of September, the Metropolitan Museum invited the Kochs—David and his wife, Julia, whose first socialite outing in New York was co-chairing the Met Gala in 1997, a year after their marriage—to flip the switch on the fountain for the media assembled, and in the presence of local politicians and functionaries, museum leaders, neighborhood schoolchildren, and a youth chorus dressed in white and wearing red gloves, who sang a dissonant arrangement of “New York, New York.”

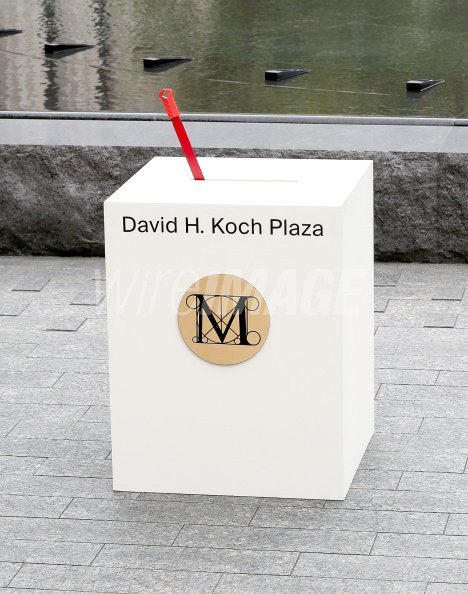

Here is the switch.

This is not a switch, but a sculpture in the shape of a switch. A giant, podium-sized, photo-legible, symbolic lever of power. Designed to embody a before and after state, a past, and a future. The museum, the greatest repository of human history, created this Here are the Kochs with then-director of the museum, Thomas Campbell. Mrs. Koch has pockets, designer unidentified, dress as-yet unaccessioned by the Costume Institute.

There are 57 more photos from the 9th by Paul Zimmerman, documenting the politicians; the students from The Nightingale-Bamford School, the private girls’ school up the street from the museum; the fountains; and the work, henceforth known as Untitled (Koch Block I), because it was first.

Here is the switch-flipped photo of David Koch—looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating, his eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread, while everyone else is turned to the fountain—which ran in his New York Times obituary in 2019.

The switch is flipped. The fountain irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This fountain is what we call progress.

The fountain, what we call progress, remains, but the work’s fate is unknown. A pile of debris, perhaps?1 The museum that created it does not document it; it is known publicly only through the mediated imagery of the pseudo-event. A pseudo-object created by the museum—the greatest treasure house of human history, built on public and indigenous land, ceded and unceded, respectively—to present to the public a pseudo-history of how the museum works: a beneficent local man and his lovely wife offered to help beautify the neighborhood by planting some trees, adding a water feature, and a place to sit.

David Koch is gone. His name remains on facades and plazas and fountains. The one single catastrophe of his inextricable political and business ventures, fossil fuels and fascism, keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. And his wife is the richest woman in the world. To this Untitled (Koch Block I) stands as a monument, wherever it is.

According to the Metropolitan’s press department, “David H. Koch said: ‘The new plaza is something that will not only beautify the Metropolitan Museum, but also Fifth Avenue and the entire neighborhood, by creating a welcoming, warm, and vibrant open space that the public can enjoy. Although the Met is best known for its magnificent art collections, inspiring architecture, and interior grand spaces, the OLIN-designed plaza will also make the exterior of the Met a masterpiece.'”

1 A masterpiece which rests on a pedestal? Thinking of how this object was handled, and where it might be now, I think of how it was made, and who made it. It was a pedestal with a metal handle inserted in a hole cut in the top. So maybe it was not destroyed in a Benjaminian pile of debris. It was repainted and reused. It could be in the museum, holding an artifact for display at David Koch’s crotch level. Right. now.

Metropolitan Museum’s New David H. Koch Plaza Opens to the Public September 10 [metmuseum.org/press]

David H. Koch Plaza at The Metropolitan Museum of Art unveiling, Paul Zimmerman/contributor [wireimage]

David Koch, Billionaire who fueled the right-wing movement, dies at 79 [nytimes]

Previously, related: Untitled (Koch Block), 2014 —