Today is the 100th anniversary of Ellsworth Kelly’s birth. There is a lot of Kelly content you can consume to commemorate. The Ellsworth Kelly Foundation has an EK100 list of public events [most of which are past] and current exhibitions.

The Glenstone retrospective is, of course, amazing, but also closed today. Unless there a whisper network of private visits on days the museum is closed? I would certainly hope so.

If you can go back in time, definitely see the Kelly retrospective at the Guggenheim in 1996, one of the most phenomenal art experiences of my life and, along with the Dan Flavin installation and Hilma af Klint, one of the the greatest shows ever installed in that museum. The Guggenheim has resurfaced a nice 2004 Q&A with Kelly for EK100.

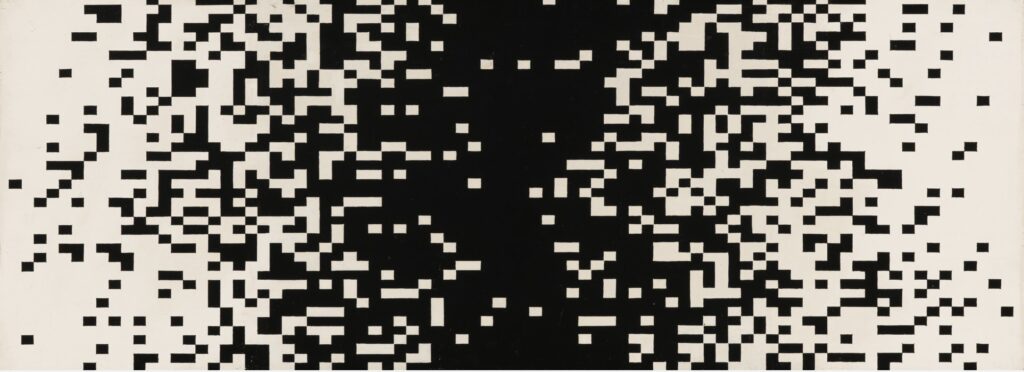

John Coplans’ 1969 Artforum cover essay is one of the first serious attempts to understand Kelly’s work on his own terms, and to recognize the foundational importance of his early work in France to his project.

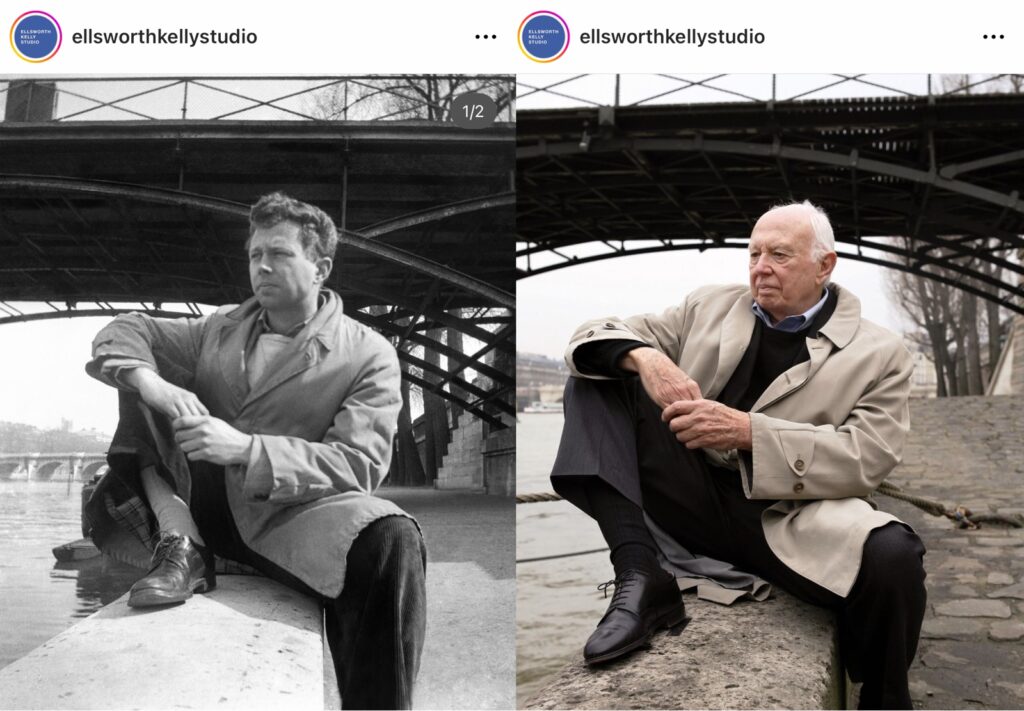

Edgar Howard and Tom Piper’s 2007 documentary, Ellsworth Kelly: Fragments screened a couple of weeks ago in Chatham, NY. Watching the trailer I recognized Kelly’s trip retracing his steps through Paris from the photos the studio posted on Instagram the other day:

I also learned that he lived above our ice cream store? We rather ridiculously had Berthillon shipped to our wedding party in NYC. Anyway, Ellsworth Kelly: Fragments is on Vimeo in full.

This all resonates with something Yve Alain Bois wrote in 1996 about Kelly’s own practice—still little understood or fully appreciated—of looping back, revisiting, and circling:

Kelly’s oeuvre is very diverse, even though his mode of thinking allows for periodic returns, canceling any attempt at pinpointing a linear evolution. Better here to state his patience: very early on, he had understood the field of Modernism as an enterprise of motivation (it is against the arbitrariness and subjectivity of “invention”-as-expression that he had coined his various strategies); at the very beginning of his career, he had surveyed this field, seen both its limits and, within those, its vast expanse of fallow territory. Because he was alone then in envisioning all at once the many possibilities it could yield, he had accepted his historical task as that of tilling this land, digging out many unexpected treasures along the way.

Now, in a culmination of remembrances of his life and work—and his practice combining the two—I wonder about his relationship to time. To the way he found something from his own past to make work from in a certain present. How long did it take? When was it ready? How did he know? What did it need? What if the indexing of works to their archival, historical sources wasn’t an accounting tedium, but a way to understand and experience the work—and the life—more fully?

“Everywhere I looked, everything I saw became something to be made,” Kelly said, “and it had to be exactly as it was, with nothing added.” How long it would take, and when it would be made, he did not say.

Kelly never sat by the same Seine twice, but he did build bridges across time, between the things he saw, and the things he made, and those bridges are only beginning to be mapped.

EK100 Centennial [ellsworthkelly.org]