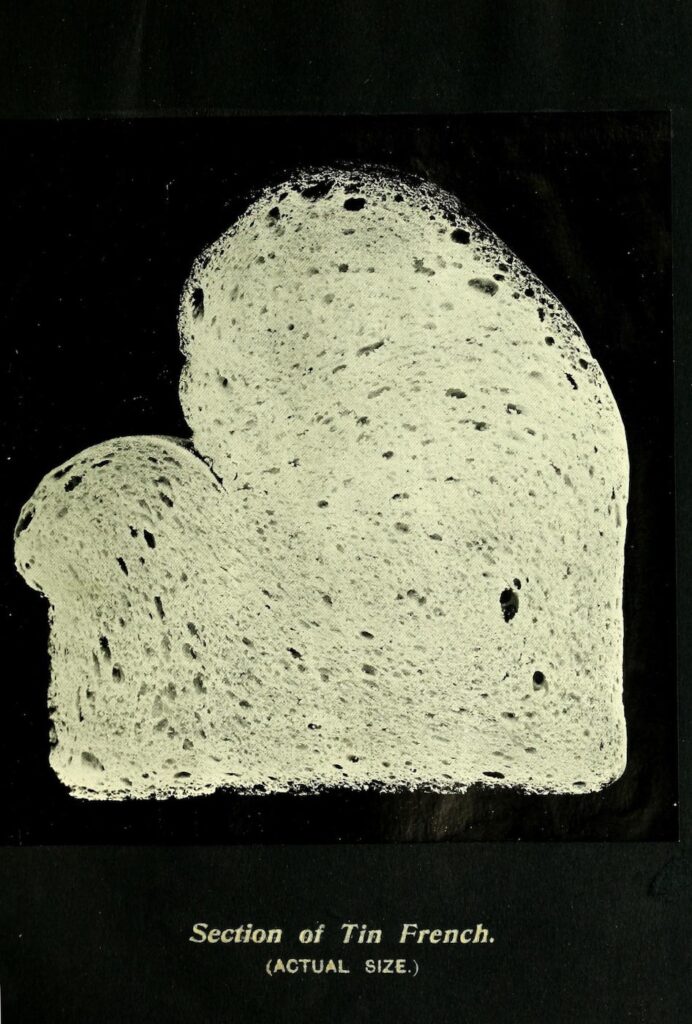

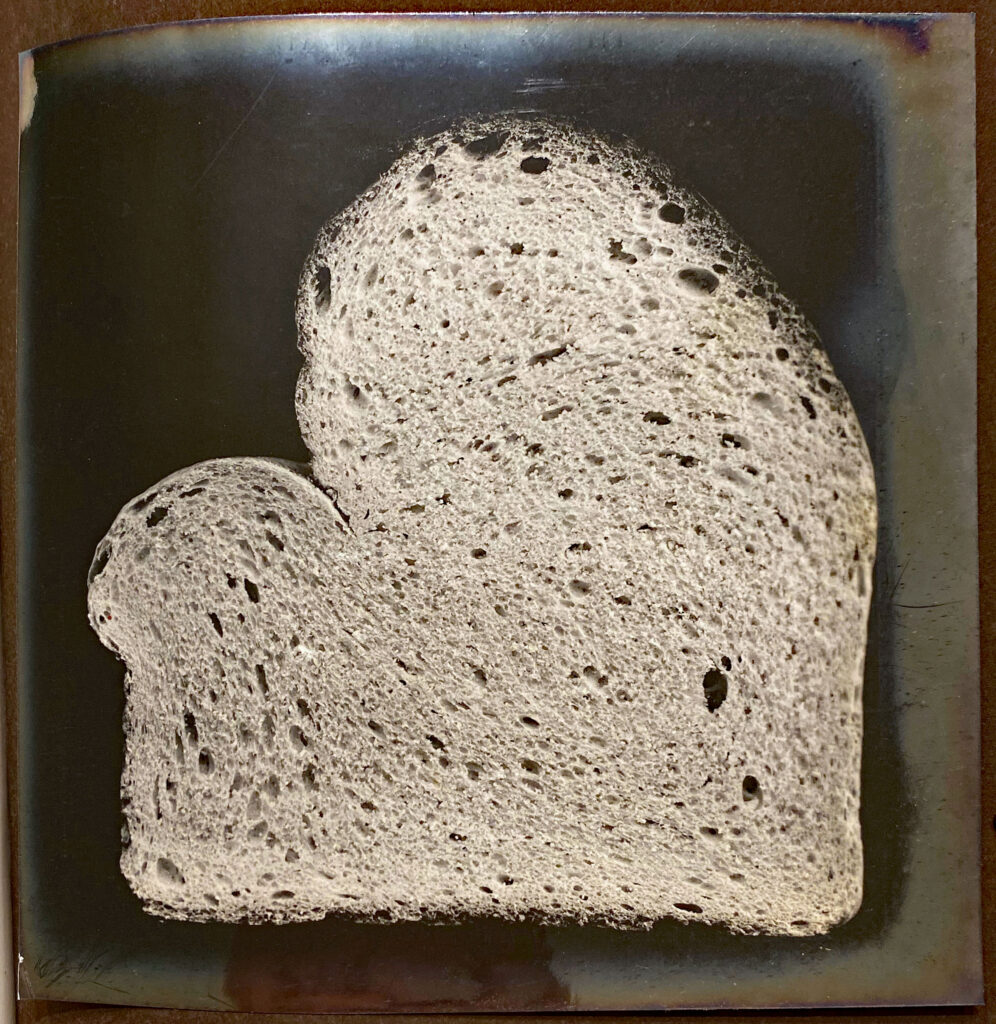

Owen Simmons’ scientific guide for commercial bakers, The Book of Bread, was published in an elaborately produced edition de luxe in 1902, and in a trade edition in 1903. The de luxe edition includes original silver bromide prints of full-size photos of various types of bread pasted in, while the trade edition uses photogravure.

Martin Parr considers it to be the first artist’s photobook, and I can’t think of a reason to disagree.

Prof. Shannon Mattern [@shannonmattern.bsky.social] brought this back to my attention this morning, after Public Domain Review posted about it in January, referencing a 2020 thread by a rare book dealer I don’t mention on a social media site I don’t link to. But that dealer’s thread did include images of the silver bromide prints, which are extraordinary, whereas the PDR scan is of the beautiful-but-more-conventional trade version.

The photographer remains unidentified.