NGL, it was not until I saw this painting of one last week at the Met that I started wondering about photographs of Manet’s Olympia.

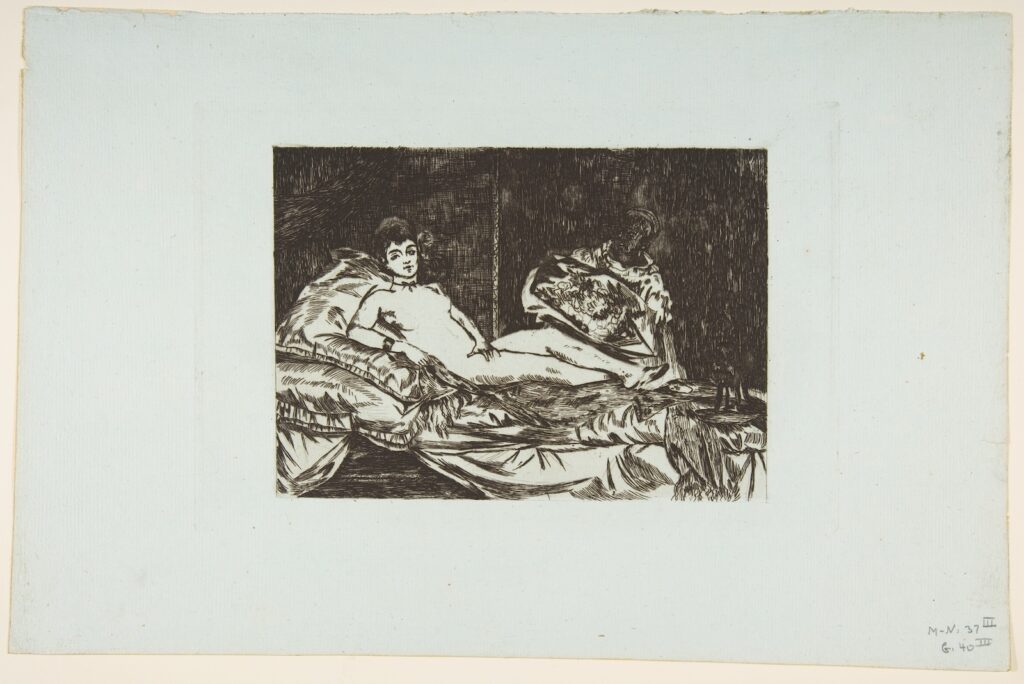

Manet never struck me as that interested in photography, but I think that assumption is wrong. Prints, primarily etchings and lithographs, were still the primary medium for reproducing and propagating paintings when Olympia was painted in 1865. Manet made two etchings of Olympia in 1867. The more tightly cropped version, known as the “small plate,” was published in the pamphlet Zola wrote defending Manet’s controversial painting. [It’s the light blue book on the desk up top, behind the quill pen. Also below:]

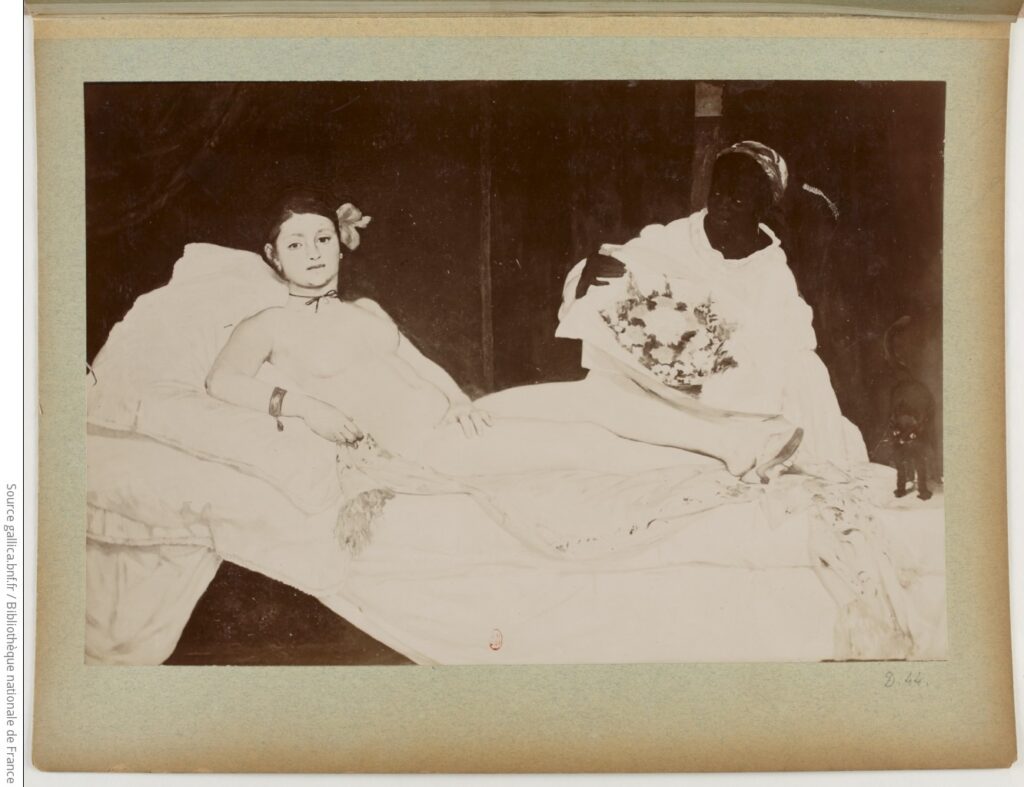

But photography was beginning to be used to document paintings, and analysis by art historians Anne Higonnet and Kathryn Kremnitzer makes a persuasive case that Manet was quite interested in the modern reproduction and circulation of images. And that Manet used photographs of his paintings in various ways to make, translate, and reproduce his work.

But there turn out to be achingly few extant copies of the photographs Manet made. Three albums of photographs in the Bibliotheque National de France, one at the Musée francais de Photographie, and two albums at the Morgan Library contain the known photos Manet commissioned from Anatole Louis Godet, beginning some time in the 1860s, plus some Godet took of the posthumous 1884 exhibition of Manet’s work. [The Morgan also holds a loosie, a single Godet print of Manet’s 1861 painting, Boy with a Sword, donated by Mahonri Young, so it’s at least possible there are more out there.] Three other albums at The Morgan, plus one at BnF, hold photos made by Fernand Lochard in 1883 for Manet’s family after his death.

In “Manet and Photography: Looking at Olympia,” a paper published in Spring 2023 in History of Photography, Dr. Kathryn Kremnitzer takes a close look at the interrelationships between Manet’s reproductions of Olympia in print, drawing, watercolor, and photography. Kremnitzer traces the possible use of photography as a reference for Manet to move between mediums. She also notes how Manet deals with the limitations of black & white etching and photography to convey the subtleties of Olympia‘s dark tones, including details of the background and, most crucially, the features of Laure, the Black model who posed as the maid.

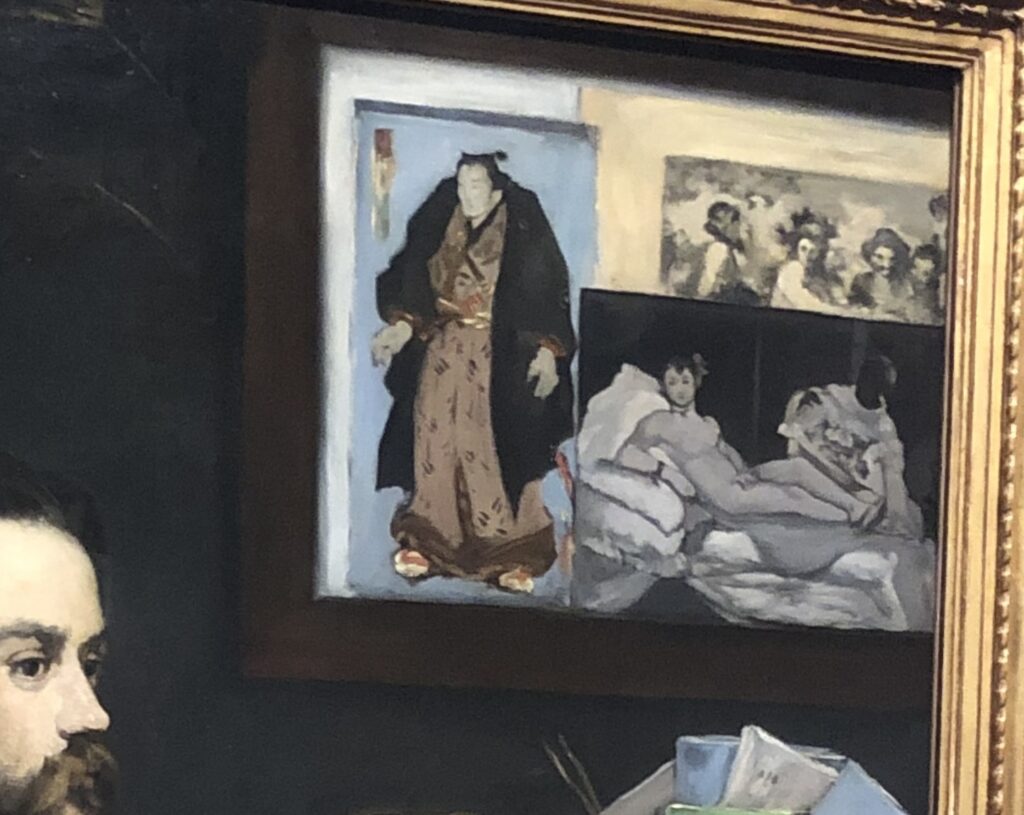

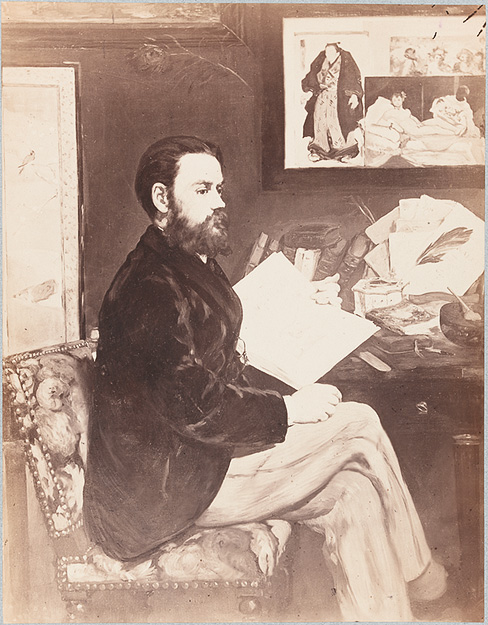

In “Manet and the Multiple,” published in Grey Room (Summer 2012), Anne Higonnet argues for Godet’s photo of Olympia as one of a constellation of specific references to image reproduction Manet assembled in his portrait of Zola. The painting of the photo sits in an overlapping group of reproductions: a contemporary (c. 1860) Japanese woodblock print, and a late 18th century print by Goya of a c. 1620s painting by Velazquez. In addition to Zola’s own pamplet on the desk (with Manet’s etching inside), Manet shows Zola reading Gazette de beaux arts, a popular periodical which began publishing reproductions of Old Master paintings in 1859.

Katharina Schmidt noted in 1999 that the spread of the Gazette Zola is holding is an 1867 essay on Goya’s Velázquez prints. Higonnet in turn traces the Gazette‘s editorial view, laid out across many issues, that Goya’s Velázquez etchings “were more important than his paintings,” but also had a “spiced flavor” that improved on Velázquez’ originals.

Woodblock prints began circulating among artists and collectors in Paris in the mid-1860s. Higonnet cites the similarities among Sumo-e prints by artists of the Utagawa School collected by Manet and his contemporaries as raising “vexed questions about originality.” In trying to even find information about Kuniaki II, I began to wonder if these similarities actually reinforce Higonnet’s point about Manet’s interest in image reproduction. Because Sumo-e print publishers would regularly reuse woodblocks to make new portraits of wrestlers, swapping out the head, or sometimes just the name in the caption, and sometimes the artist’s name. It’s hard to imagine Manet parsing the details of wrestler names in kanji, but easy to imagine him interested in the formula as much as the form.

And what of the Portrait and its subject? Godet photographed it, of course. And in 1900, Émile Zola photographed it, too, in his own home. By that point, this image of the revolutionary art critic surrounded by the props of a man of letters that Manet had provided, became the subject of its own vortex of circulating images.

From its debut in the Salon of 1868, Manet’s portrait served as the first public visual representation of Zola, and it stuck; As Maya Balakirsky Katz wrote in 2006, Zola didn’t write art criticism for a decade after its debut, and he didn’t contribute to the subscription for the Louvre’s acquisition of Olympia. And as Zola continued his ascent into France’s elite, Manet’s portrait served as the basis for a lifetime of caricatures in the popular press where he got his start. Zola apparently collected them in a scrapbook of his haters, which was guarded by his family.

[note: Thanks to Kathryn Kremnitzer for her insightful research, and for her recommendation of Anne Higonnet’s paper on Portrait of Emile Zola.]