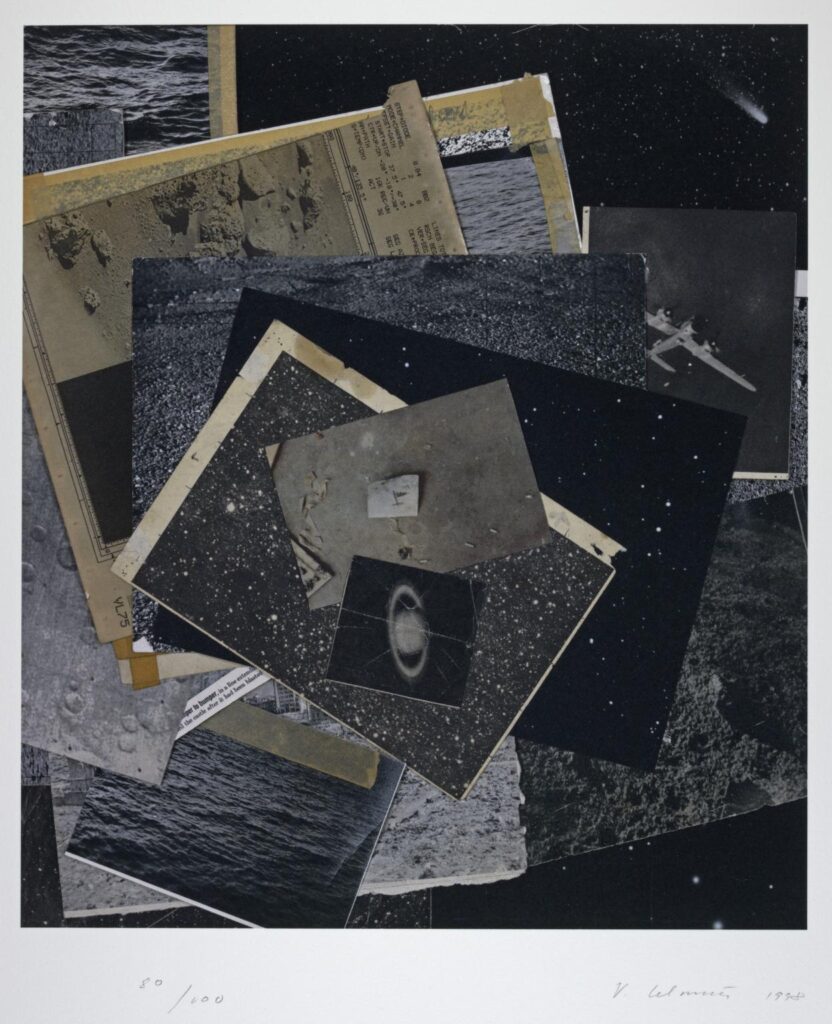

When @garadinervi posted Vija Celmins’ 1999 Iris print, Untitled (Source Materials), it baffled me. It felt familiar, yet I’d also somehow missed it for 25 years? It’s an edition of 100, yet there are almost none in the aftermarket churn?

Tate shares either ed. 76/100 [via the text] or ed. 80/100 [via the pic] with the National Gallery of Scotland as part of the Artist Rooms series, acquired in 2008. SFMOMA has ed. 78/100, but theirs is just Untitled, and dated 1998, but they got theirs in 2000. Clamp Art Gallery has one for sale online rn, and their ed. number looks unfilled in, or photoshopped out. It all seemed very unfixed.

More to the point, how did this work exist, and yet not only did I not know it, I didn’t have it? Turns out I did, and I did, and then I very much didn’t, and I don’t.

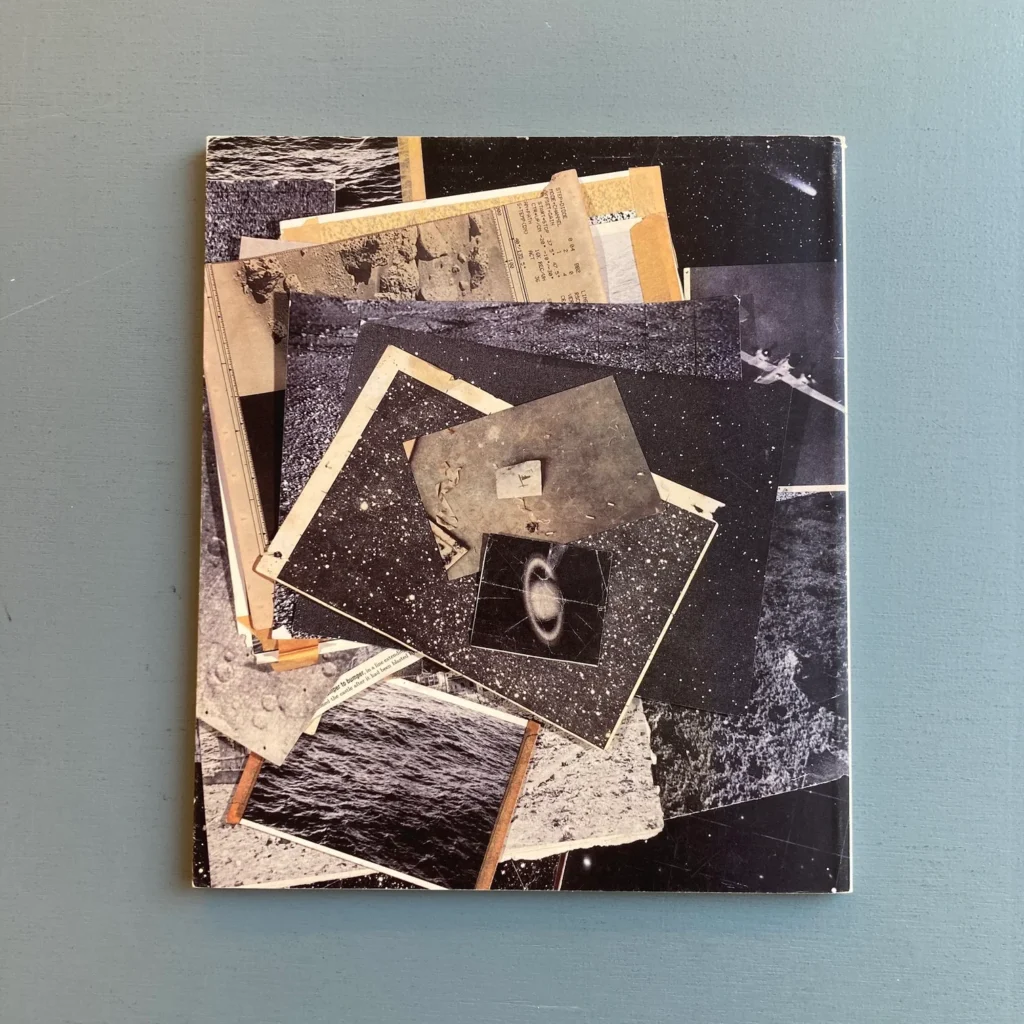

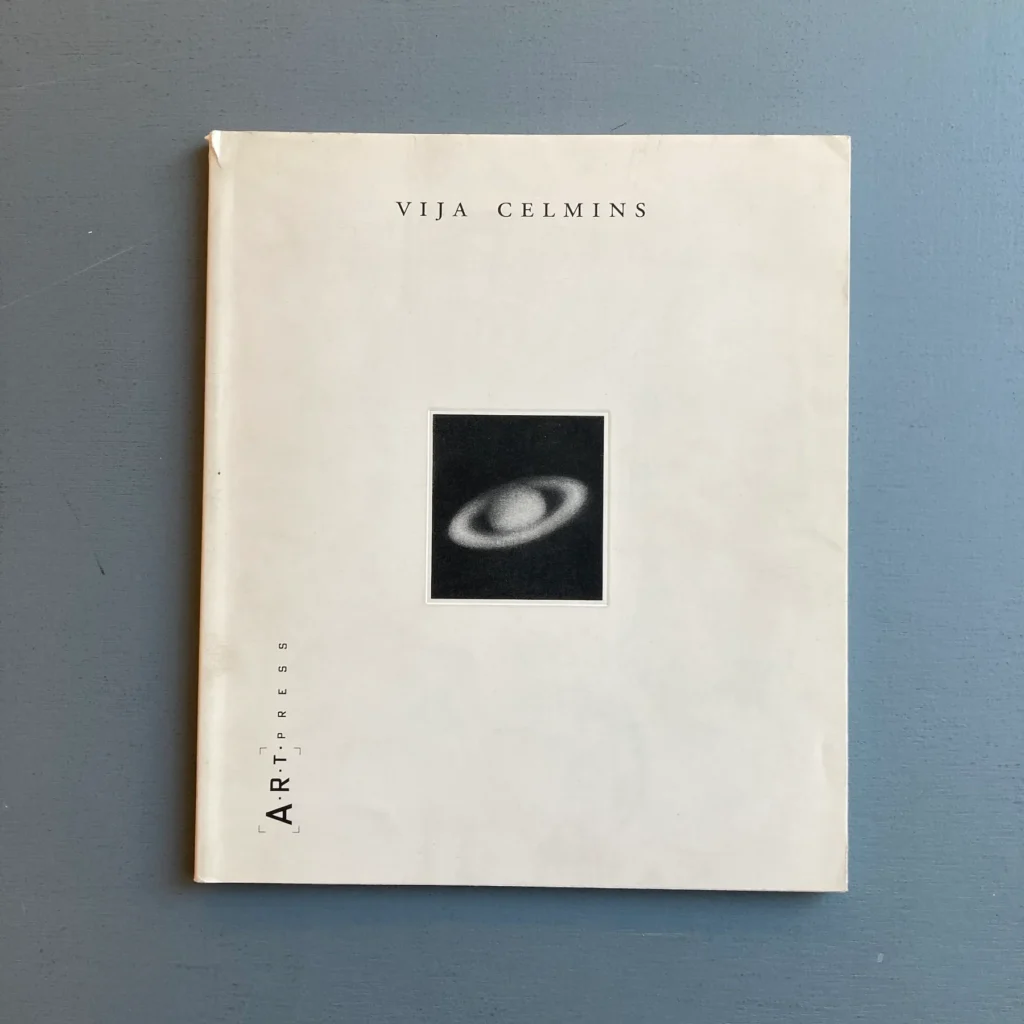

I Google image searched my way to Saint Martin Bookshop in Belgium, where I realized the image looked familiar because it’s on the back cover of Celmins’ first monograph, published by A.R.T. Press in 1992, which I have. The image credit is just “source material.”

But the A.R.T. [Art Resources Transfer] connection matters. Because this was one of fourteen Iris prints in the A.R.T. Press Portfolio in 1999, published in collaboration with DC gallerist David Adamson. Adamson showed the portfolio in February, so SFMOMA’s date of 1998 can work. Except the Brooklyn Museum has the entire portfolio [ed. 19/100, hometown advantage on getting the low numbers], and it’s all dated 1999, including the Celmins, which is just Untitled. Which, fine.

Except neither SFMOMA nor Tate seem to have the rest of the portfolio. If SFMOMA bought a loosie in 2000, I’m guessing that after an initial surge of sales, Bill Bartman, A.R.T.’s scrappy hustler with a heart of gold, either wholesaled a bunch of sets, or started dealing from the bottom of the stack himself, selling whatever was in demand.

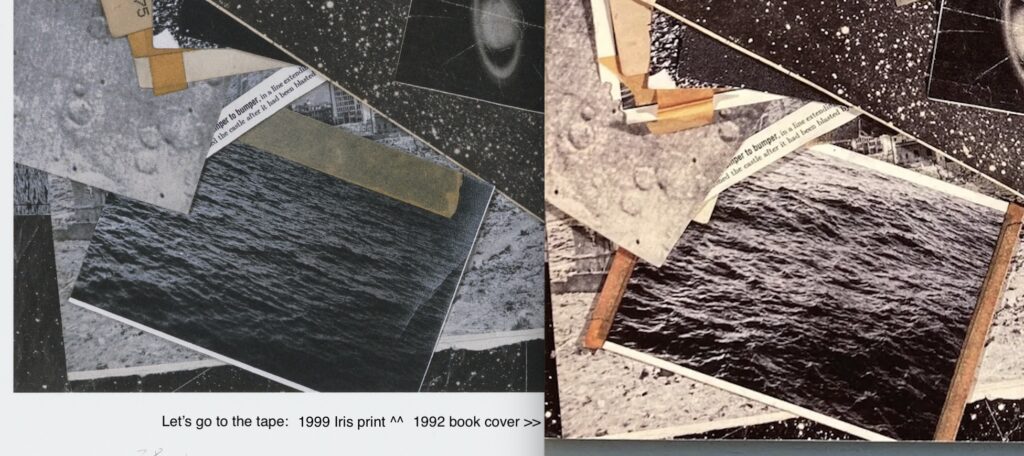

In 2019 Rago dumped an incomplete portfolio—12 unframed prints, minus the Richard Artschwager and Chuck Close, which they’d sold in May, both ed. 8/100—in an unreserved sale in August. Here is the Celmins. LMAO what is going on it is tiny. AND UPSIDE-DOWN. Were later ones just printed bigger? Is every gallery and museum stating their dimensions and cropping their image differently just for fun? Can we all agree to at least differentiate sheet size and image size?

For Celmins especially, the actual size matters. It is part of her project. The cover of that 1992 monograph reproduces Saturn, a 1985 mezztotint, and makes the point that it’s “actual size.” Of the image, at least: the book is 10 x 8 1/4 in, and the print is on an 11 x 9 1/4 in. sheet.

Which means the source materials image on the back cover is reproduced at slightly smaller than actual size. And which means that the Portfolio print IS actual size. I apologize for calling it tiny. At first I thought the Iris print was just a blown up version of the book cover photo . Then I thought it was a carefully enlarged version of the book cover photo. Then I realized it is actually a digitally composed recreation of the book cover.

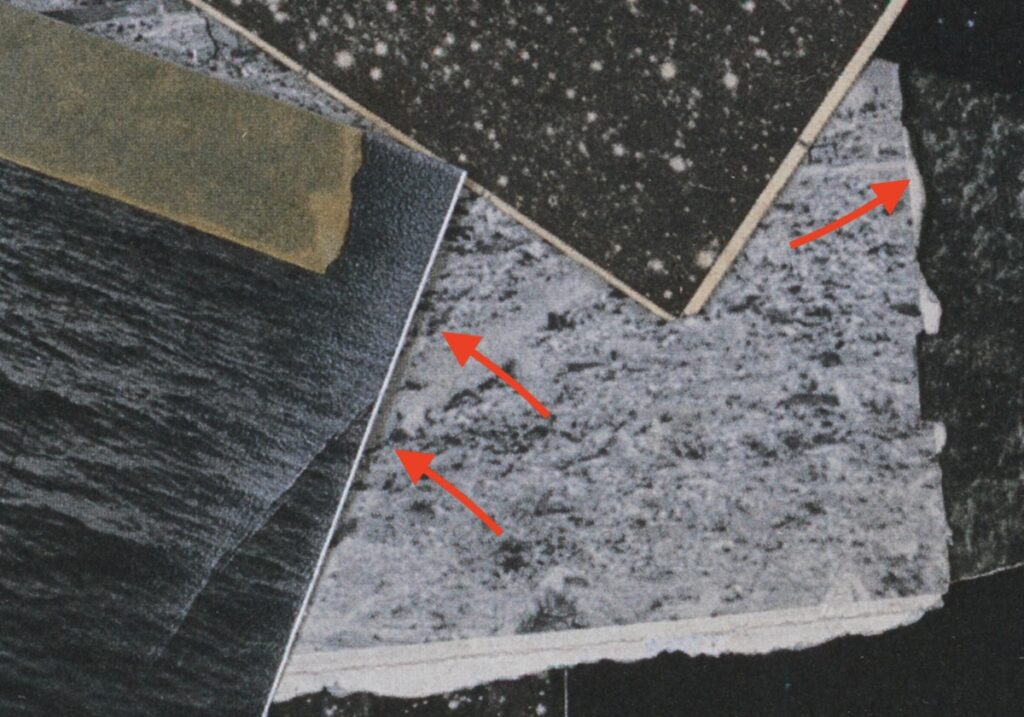

In the Tate’s extended summary text for Untitled (Source Materials), Stephanie Straine wrote in 2010, “The photographs and clippings featured in Untitled (Source Materials) were selected from the artist’s large collection of paper ephemera, hoarded by Celmins over the course of thirty or more years. They were then scanned individually, cleaned digitally, and assembled to produce a file enlargement, which was printed as a single inkjet print in one process.” Which, what? Wow, yes they were.

Celmins has a robust and mesmerizing practice of making painted bronze versions of objects like stones, rulers, and chalkboards. She appears to have extended it here to photos—and photos of photos. Extended is probably not the right word, though, since her meticulous image making practice has been focused on flat objects like photos, clippings, and torn pages, since the late 1960s. It may not have always been as obvious as it is in Source Materials, but whether they showed stars, deserts, oceans, or spider webs, Celmins’ paintings, prints, and drawings have been of photographs. She talks about this interest in photos with Close; it’s in the book.

What stands out here, though, are the little differences. While rocks and bronze facsmilies can seem visually indistinguishable, the images of a stack of source material seem designed to index the many changes throughout. Like Morandi still lifes, but flat. Or mostly flat. There are still some shadows in the Iris print [above], which don’t make sense if it’s a digitally layered composition. They could have been added, of course, but it could also be possible that Celmins created cleaned up physical replicas of each image source—I might call them object facsimiles—and stacked them IRL for [re-]photography. That might account for shadows, but also for the apparently entirely different night sky photo four layers down.

All of this in one digital print in a fundraising portfolio—and in a medium that won’t last. In 2021 Tate conservator Jordan Megyery analyzed early Iris prints, which became very popular in the 1990s, and found they are extremely unstable, and susceptible to light and moisture damage. At least now I can move this from my list of things I wish I’d bought in the 90s to things I’m glad I didn’t.