In 2012, in her new post as director of the Tensta Konsthall, a community-focused art center in suburban Stockholm, power curator Maria Lind tried to figure out if there is ethical abstraction under capitalism. From “Abstract Possible: The Stockholm Synergies,” her four-month, three-venue exhibition and art economics report, the answer can only have been: lmao no.

It’s at once wild and stupefying to look back at the critical discourse around this show, which was controversial? provocative? depressing? abjectly cynical? hopelessly naive? Is this really what people were worrying about in 2012? Or was it just art people in Sweden?

Lind’s group show at the Konsthall was a thoughtful but precedented look at contemporary artists’ reckoning with the conflicted historic promise of geometric abstraction. Mika Tajima’s rack of surplus Herman Miller decorative panels popped on the gloss black monochrome plane of Wade Guyton’s plywood floor. All good. The reworking of a class room in the fashion department of Stockholm University sounds positively quaint. It was the third venue—a two-week selling exhibition at Bukowskis, the Nordic auction house then owned by the Lundin family, some of Sweden’s most toxic billionaires—that caused reviewers such grief.

It is only finally through reading Sven Lütticken’s later, broader essay on abstraction and Lind’s interview with Silvia Simoncelli that Lind’s fundraising hustle is revealed to be a critique of the investment-driven, public/private economic structures of the art world. Or is it the other way around?

She described the Bukowskis show as “a typical case of outsourcing rather than a collaboration.” So instead of curating too much—besides one loose sheet of Guyton plywood, almost half the show was from Mika Tajima’s spraypaint on acrylic “Furniture Art” series—Lind used her Bukowskis curatorial fee to pay for a book she edited with Olav Velthius, Contemporary Art and Its Commercial Markets: A Report on Current Conditions and Future Scenarios.

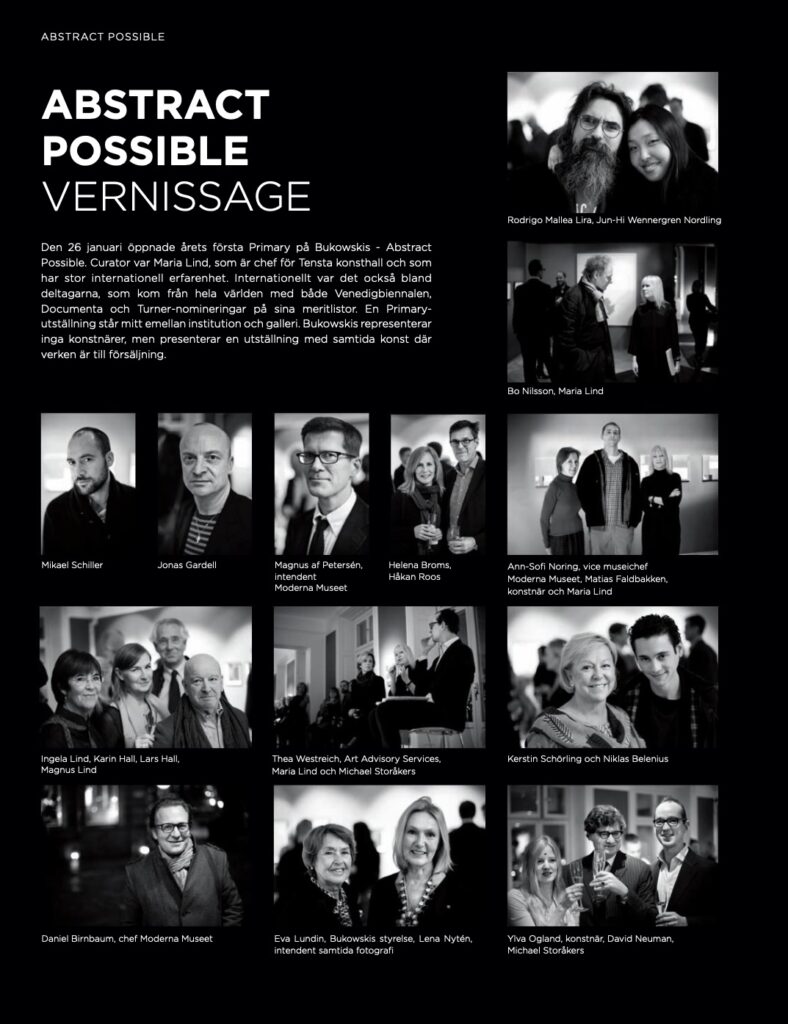

Then she hired a pair of artists in the show, Golden+Senneby, to create the show “concept.” They, in turn, commissioned Mara Lee to write “a policy poem” of instructions for handling the show, which was only disclosed to Bukowskis staffers. [One hint at its contents: works went off view as soon as they sold.] And they invited art adviser Thea Westreich to estimate the value of the 55 works in the show, and provide a comprehensive report and market analysis. The report was sealed in a custom-made box and included in the show as an art object, Abstract Possible: An Investment Portrait (2012). This expert info was intended, Wu Tang album-style, for the sole private benefit of whoever bought it. Also they invited Thea to the opening.

Now, twelve years later, Goldin+Senneby+Westreich’s greatest collab ever is back on the market [sic], and it does not look like it has been opened. So the expensive, exclusive knowledge of one of the 21st century art world’s most distinguished experts remains to be discovered. What invaluable secrets might it teach us about the art market and the society around it?

Will it reveal how the speculative market for work by Wade Guyton, the standout auction star of Abstract Possible, would contract so hard that the “Distinguished European Collectors” who owned that 300,000 SEK plywood edition would be unable to sell it not once, but twice? [Or actually three times? If the Phillips provenance of 2019 is correct, and the Guyton came directly from Gisela Capitan, was it consigned to Abstract Possible/Bukowskis, too? And would that make the Tensta black plywood floor a promotional tie-in for the Distinguished Collector? And did at Collector also own the auction house?]

Speaking of the Lundins, does Westreich’s report paint a portrait of the oil drilling family’s hiring of a crisis management company to improve their negative public image; and their use of Bukowskis to wine and dine Swedish business, political, and cultural leaders as early as 2011 [pdf]—oh hey, right when the show happened—because they were facing what would become Sweden’s largest ever war crimes investigation, relating to the Lundins’ collaboration with the South Sudanese military during the civil war? Oh wow, that trial finally started just last month.

Or would Westreich’s 2012 report reveal how Bukowskis’ strategy of turning to the emerging Russian auction market would not go so well after Russia’s invasions of Ukraine, and how the Lundins would end up selling Bukowskis to Bonhams in 2022, part of a private equity rollup of regional auction houses begun in 2018?

What could the buyer learn from Westreich’s 2012 analysis that they didn’t already know from Andrea Fraser’s 2011 Texte zur Kunst essay, “L’1%, C’est Moi,” which she also published as her entry to the 2012 Whitney Biennial, where she synthesizes extensive economic research to show that “art prices do not go up as a society as a whole becomes wealthier, but only when income inequality increases,” and that art investments doing well is “disastrous for the rest of the world”?

And what would the buyer of Goldin+Senneby’s 2012 Westreich art investment report learn from it that they couldn’t learn directly from Westreich herself who, in 2015, with her husband Ethan Wagner, donated their own art collection—over 800 works—to the Whitney Museum and the Pompidou?

So far, at just 35,000 SEK, barely a quarter of its 2012 price, bidding for the Goldin+Senneby/Westreich portrait has not reached the reserve price. There are still three days left, but at this point I’m pretty certain that past performance is no guarantee of future returns.