Does Hauser & Wirth have a conventional commercial relationship with David Hammons? As Zhou Enlai said when Henry Kissinger asked him about the impact of the French Revolution, “It’s too early to say.”

In a just-published oral history Marc Payot, a president at Hauser & Wirth, remembers the early days:

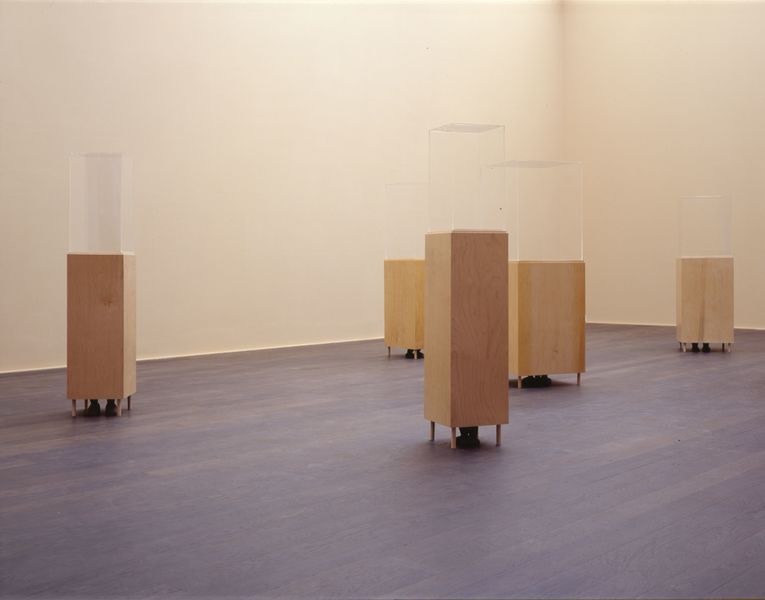

In the early 2000s, Iwan [Wirth, co-founder and president, Hauser & Wirth] and I started having discussions with David that began with the help of Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn [founder, Salon 94], who was working very actively with him, and Lois Plehn, who serves as David’s agent. Quite soon, he decided to do a show with us in Zurich, an installation of cardboard boxes filled with scavenged clothes and stacked on wooden pallets called Made in the Republic of Harlem. There were labels printed on the boxes that said, “Made in the Republic of Harlem,” giving them a Warhol-like feel, which was interesting. In an adjoining gallery he showed Hidden from View, wooden museum pedestals topped with plexiglass cubes. Cubes like this would normally contain objects, but David left them empty. The feet of small African-like sculptures could be seen peeking out from beneath the pedestals, all but concealed. The sculptures were amazing—David’s way of making something seemingly unremarkable look iconic.

In her 2005 essay, “An Elective Affinity,” curator Claire Tancons examined the Zürich show in the context of Hammons’ preceding emptying of the exhibition space, Concerto in Black and Blue, a Black Cube critique of the White Cube. Tancons’s overarching analysis is of Hammons’ and other artists’ critique of the treatment of African art and culture by both the Modern and Postmodern movements of western art. From André Breton to MoMA’s William Rubin, “primitive” and “tribal” African artifacts are not just appropriated, but valorized and elevated to the status of Art, turning it into a readymade.

She quotes Sally Price: “[Western connoisseurs] essentially see themselves as doing for African sculpture (for example) what Andy Warhol did for Brillo boxes or, more strictly speaking, Marcel Duchamp for urinals.”

The actual text on Hammons’ “Warhol-like” boxes filled, purportedly, with used clothing purchased, not scavenged, reads “Made in the People’s Republic of Harlem.” Unlike Warhol’s boxes, they sit on integral pedestals, a la Brancusi, collapsing the twin threads of Modernism—Primitivism and the Readymade—into one. Hammons asserts a Black sovereign, anti-capitalist presence while critiquing white colonialism across the entirety of institutional art history, or as it’s known in the gallery business, “making something seemingly unremarkable look iconic.”

Hauser & Wirth held onto at least one Untitled (Hidden from View) vitrine work for twelve years, until 2015, when they placed it in “a prestigious American collection.” There it stayed for nearly ten years—and counting? It turned up at Sotheby’s last week, but didn’t sell.

In her final note in “An Elective Affinity,” Tancons writes:

I have made no distinction between the museum and the gallery, seeing the latter as the commercial counterpart of the former; both share the same modernist tactics of display. However, I do believe that Hammons’s choice of a gallery setting for some of his works is not the result of chance, and that the influence of commercial galleries on contemporary artistic practice could be analyzed in the same way that Kynaston McShine analyzed the influence of the museum on the artistic practices of the twentieth century.

So yes, this is all a conventional commercial relationship. It is inextricably linked to museums. And not only does even the most candid and privileged account of the most involved people leave out crucial aspects of an artwork’s importance, it does so by design.

Claire Tancons’s essay is in Kellie Jones’ 2025 reader, David Hammons [mit]

the H&W David Hammons Oral History is in Ursula Issue 12 [hauserwirth]