Donald Judd’s “Una Stanza Per Panza” is a fascinating, rambling, exasperated defense of the primacy of the artist in making and making decisions about his work, threaded through a fierce, bitchy, gossipy rant about the pomposity and presumptuousness of problematic and profiteering collectors. And dealers. And museums. Some museums. The ones who didn’t support working artists for decades, but who then give tens of millions of dollars to a collector who made grand, hollow promises to hoover up works on the cheap.

It was all driven by the years-long conflict with Giuseppe Panza over the terms for realizing artworks, sold by Leo Castelli as certificates or plans on paper. Judd’s understanding was that these were permanent, site-specific installations to be constructed under his supervision. Panza saw them as authorizations to make Judd sculptures when and where he desired, including making local copies for museums, and for sale. The evolving realization [sic] of how far apart these views of art were is a subcurrent of Judd’s 25,000+ word text. Though whatever his position at any given moment or paragraph, Judd never wavers in his own rightness.

Written and published in 1990, “Stanza” is an important primary document, at least as it captures the mature, powerful artist’s retrospective view of his experience and his practice. I have to imagine not every principle of how to fabricate a Judd, and how to judge its authenticity, was born fully formed, but had to take shape in response to the questions that arose along the way.

The Judd Foundation has a PDF available, and it’s included in the 2016 edition of Judd’s writings. In 2021 the Brooklyn Rail published “Una Stanza per Panza” online, and as a standalone print supplement, with a helpful introduction by JF archive director Caitlin Murray. I have not seen it in its original form, published as four installments in the Bonn-based journal Kunst Intern, but I bet it slaps even harder in German.

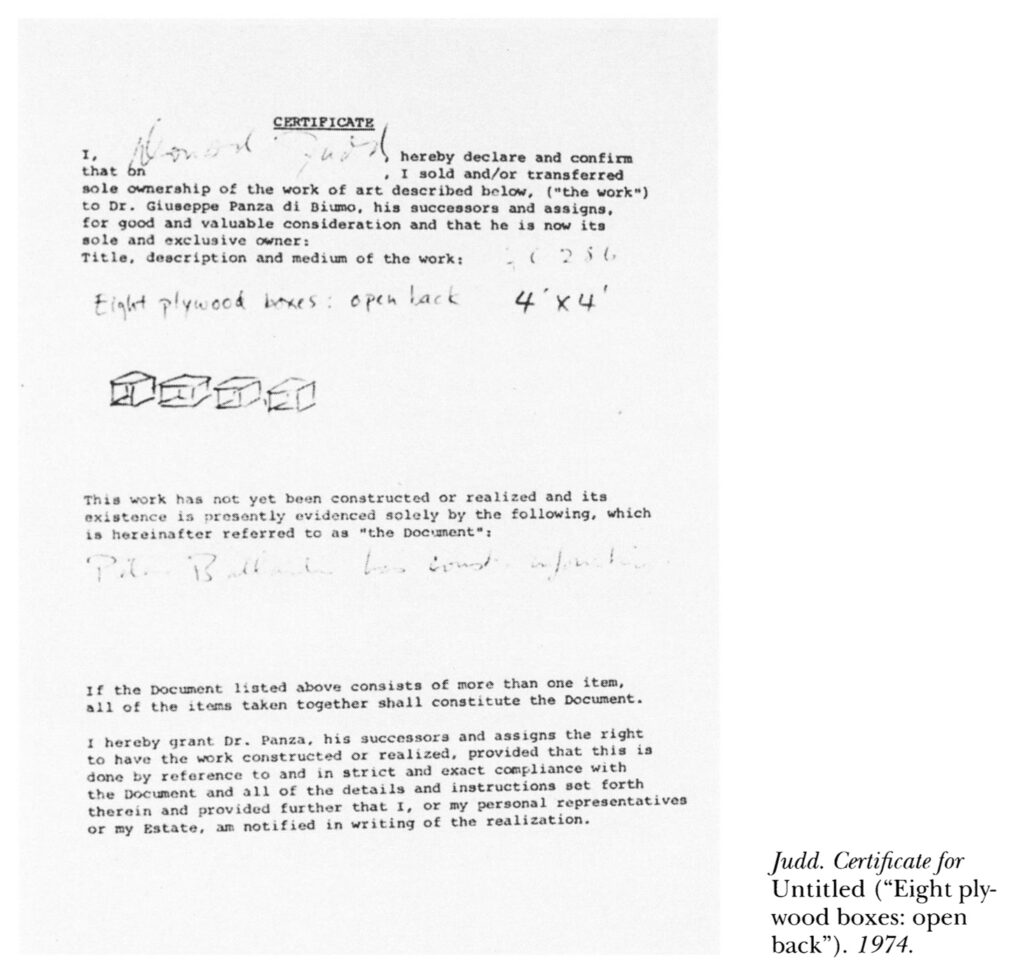

In the Fall 2009 issue of October [pdf], James Meyer published an extensive essay, commissioned by the Guggenheim, about Judd’s dispute in the context of Minimalism. Also Dan Flavin’s dispute, because Flavin had similar, incredible experiences with Panza, who fabricated and installed fourteen rooms of Flavins at the Reina Sofia without the artist’s approval, involvement, or knowledge. This wider view, though, is helpful for tracing the shifts in Judd’s perspective of his own work over time and experience. Also, Meyer publishes one of the Panza Judd certificates, the expansive language of which is a work of art in itself. Which, when it turns out the lawyer was the one who signed Judd’s name to it, makes a teeny tiny amount of sense.

Re-reading Judd recently, and even though I knew full well that the Chinati Foundation was the result of Judd suing Dia, I was surprised the intensity of Judd’s scorn for the de Menils. But Michael Kimmelman’s sprawling 2003 history of Dia’s chaotic ambitions and financial recklessness put that in context, too.