That’s it. That’s the post.

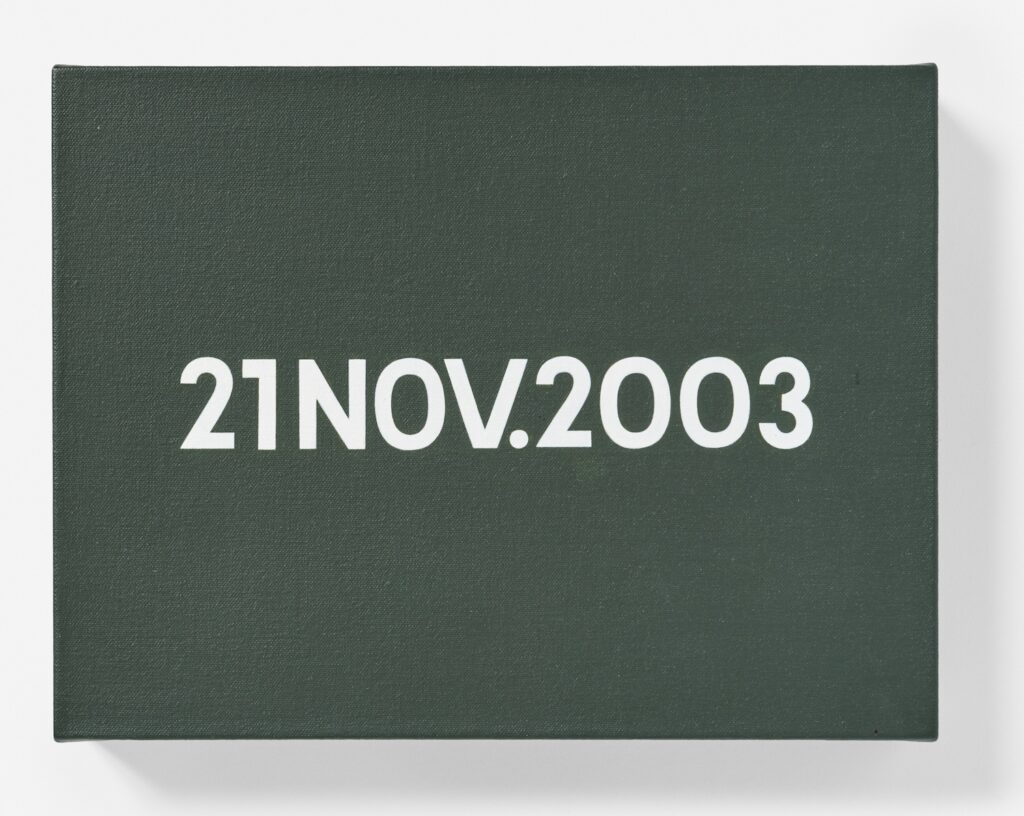

It can sometimes feel like the work On Kawara left behind is so vast, constrained, and specific that it leaves anyone with questions—or answers—about the artist and his practice stuck in critical fabulation. But that turns out not to be true.

Beneath Duncan McLaren’s occasionally rhapsodic biographical reconstruction of Kawara’s career lies an extraordinary amount of data drawn and synthesized from the work itself. The artistic actions of a day or an instant—where Kawara was when he painted, who he sent postcards to, where he went, and who he met—now create a structure of a life.

And when McLaren sees that one neighbor got dozens of I GOT UP postcards, and another got only one, he tracks them down and asks what happened. And that is how we find out how Nobu Fukui, the guy who organized their artist co-op building, and hosted their late night mah-jong, and stored his art & stuff at the Kawara’s when he went back to Japan, also got in some date painting trouble:

On normally brought a painted canvas [to mah-jong] with the date pencilled out, all he had to do was to paint. Sometimes he came with a blank canvas, painted the canvas and played the game while the paint was getting dry. He used a set of plastic templates to draw dates with a pencil. I didn’t know, but I learned later that somehow he kept this a secret. Apparently he wanted the public to believe he was drawing freehand.

The typeface changed over the years; would it be a shock to learn that Kawara used a template for some of those styles? Actually, yes, but only because of how the project evolved and was presented. And a template at the beginning does seem—and look—plausible, if unexpected. But this posthumous disclosure is only part of the drama. Here is McLaren:

Nobu told me that on his 25th birthday, on June 2, 1967, Nobu borrowed On’s templates and made a Date Painting on an orange background, the characters being displayed both upside down and running backwards…

Later in 1967, when Nobu was going to Japan for several months and was giving up his rented loft, On and Hiroko offered to store his birthday Date for him. Upon Nobu’s return from Japan, On did not give him back the Date. Mind you, Nobu didn’t ask for it back, so maybe there was an unspoken understanding that Nobu had been in danger of somehow undermining On’s project.

June 1967 was just over a year in. It already became clear in late 1966, when he destroyed a date painting that took longer than a day to finish, that Kawara only settled the conceptual contours of his painting project over time, as he experienced it. Was having someone else paint a Date painting ever OK? How about finding out your punk friend, ten years younger than you, painted a flipped stunt version of a Date painting for themselves?

Was Nobu the first person to inspire the Date painting-as-birthday-gift, only to play himself in the process?