In the instagram post at __artbooks__ it says On Kawara wrote this “personal chronology” on stationery from the Downtown St Louis Holiday Inn, “some time between October 16 and 20, 1973.” The timing is based on the assumption that he didn’t just grab the stationery for later use, but instead wrote out this list while he was staying in St. Louis. It’s also possible that another sheet stapled under this one—these are photocopies, and were not known to the One Million Years Foundation that handles Kawara’s estate—continues with all the places he’d been, ending with Pittsburgh and Indianapolis, the places he’d visited before arriving in St. Louis.

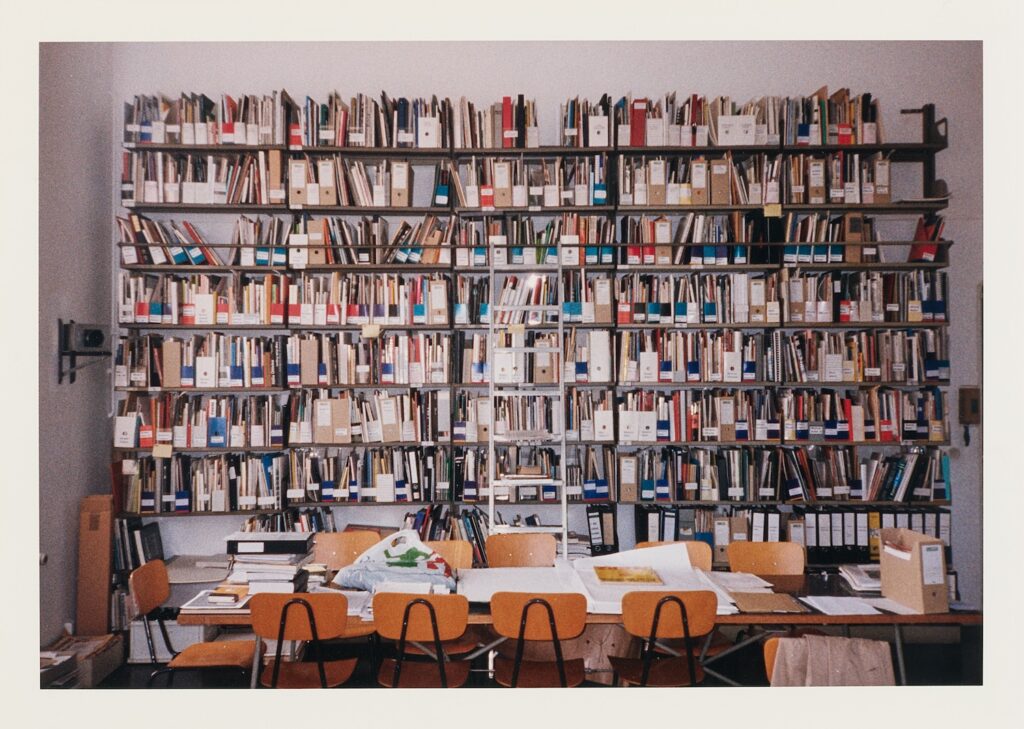

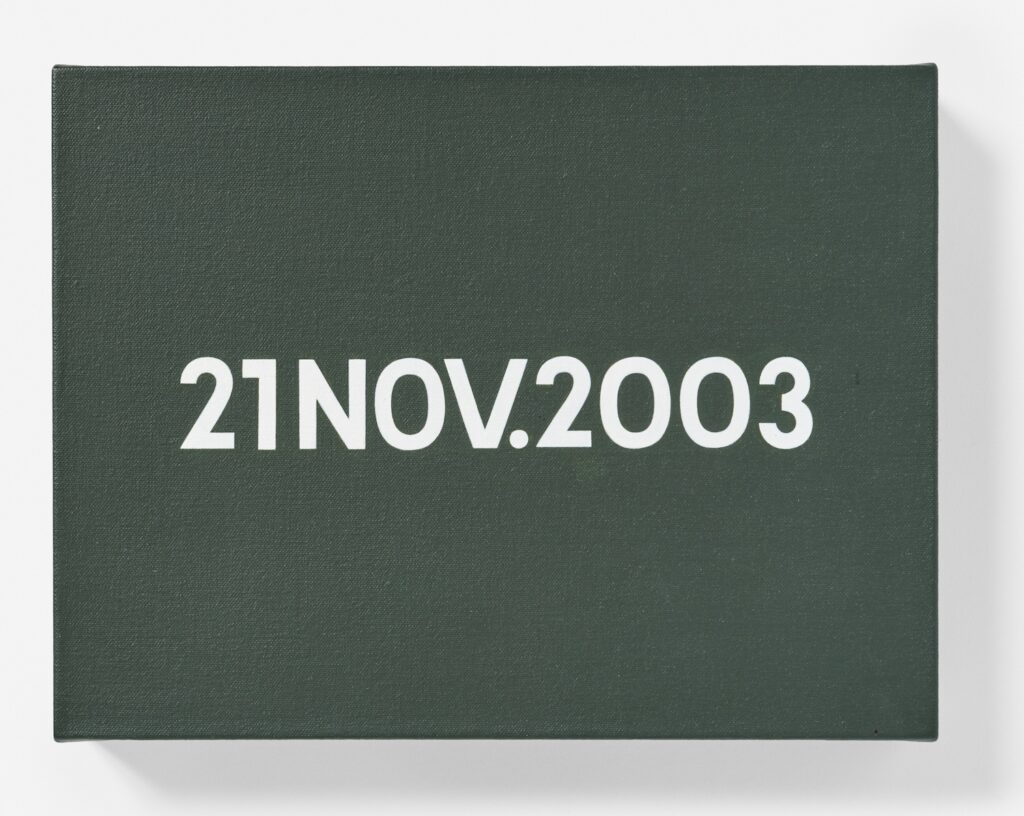

In mid-October Kawara and his wife Hiroko Hiraoka were barely a week into a three-month road trip across the United States, making art along the way: Date Paintings, I Am Still Alive telegrams, I Got Up postcards, and I Went maps. The postcards for the four mornings he woke up in the St Louis Holiday Inn were all sent to Sol Lewitt. Between the postcards and maps in the On Kawara Database at Tama Art University and Duncan MacLaren’s extraordinary reverse-engineered narrative, it’s possible to reconstruct the form of Kawara’s life, if not the substance.

This chronology, sort of an I’VE BEEN, is only loosely related to the I WENT project. Every day from June 1, 1968 through September 17, 1979, Kawara traced the path he traveled on a photocopy of a local map. It hints at broader documentation of his life alongside his work, if not for it. But it also shows Kawara looking back, a perspective that rarely surfaces in an art practice so thoroughly grounded in the moment of its making.

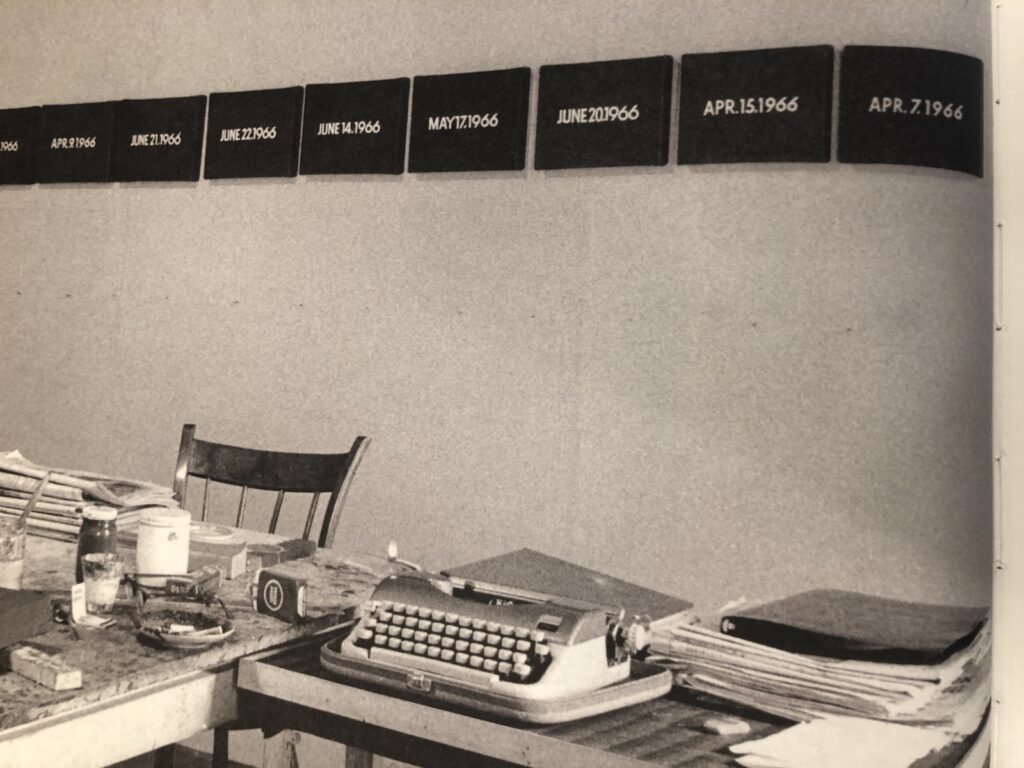

![a black and white 1966 photo of on kawara's loft studio with two rows of date paintings along the wall: the smaller ones are hung in a line, and the medium sized ones are lined up along the floor. a giant date painting, perhaps 6 by 9 feet, of sept. 20, 1966 rests on blocks on the floor in front of the rows of smaller paintings. [spoiler] it was later destroyed, presumably because it had taken longer than a day to finish it.](https://greg.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/on-kawara-studio-1966-sept20.jpg)

It reminds me of a glimpse into the evolution of Kawara’s project that I read recently on MacLaren’s page reconstructing the first year of the Date Paintings, 1966. Among the photos of Kawara’s 13th St studio I’d seen many times before, is this image of the largest date painting to-date, Sept. 20, 1966. McLaren points out, though, that Kawara does not record making a painting on the 20th, nor on the 21st, 22nd, 23rd, or 24th. Yet there one is.

This giant painting, then, was perhaps the first one Kawara could not finish in a day. And so it was almost nine months into his project, and only after completing and photographing his biggest painting ever, that Kawara decided a Today Series painting must be made on the day, or it had to be destroyed.

__artbooks__ [ig]