When DC art lecturer and blogger John Anderson emailed to ask if I’d heard about the scandal surrounding the Washington Gallery of Modern Art and the Tom Wesselmann, I was like, “Tom Wesselmann scandal? Do tell!”

He pointed me to Nina Burleigh’s account of it in A Very Private Woman, and now that I’ve read it, I’m kind of confused.

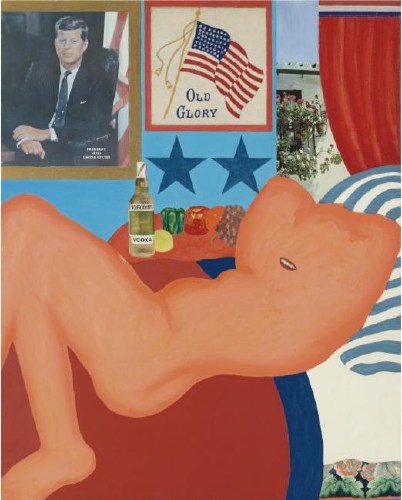

According to Burleigh, the problem involved Wesselmann’s Great American Nude #44, 1963 [top], which was included in Alice Denney’s “The Popular Image Exhibition” in April 1963. Several of the Gallery’s trustees previewed the show and “questioned the propriety of the collage” which included “a framed portrait of the president of the United States with the silhouetted nude body of a movie star,” who was interpreted to be the recently deceased Marilyn Monroe:

[The trustees] called for a personal meeting with Alice Denney. They demanded that she remove Tom Wesselmann’s Great American Nude No. 44 from the show. “It was ironic, because we all knew what was going on at the White House,” said Denney’s assistant at the time, Eleanor McPeck. “Kay Graham and Marie Harriman and some others insisted this picture be taken down and taken out of the show. The board was very conservative. They were simply not prepared for it.”

Alice Denney objected, but the board members were the museum’s financial lifeline. Reluctantly, the curator prepared to take the Wesselmann down. But behind the scenes the matter had come to presidential attention. Mary Meyer, by then one of the president’s occasional lovers and a confidante, told him about the little art imbroglio. She described the Wesselman collage with the Monroe nude beneath his official portrait. She told him about the ladies of the gallery board, all in a dither. The image of grande dames such as Marie Harriman scrambling to protect his reputation was too funny. The president laughed at the story and told Mary to tell the little Gallery of Modern Art that he wanted the Wesselmann to hang. The collage stayed in the show. [pp. 182-3, footnote: Alice Denney, Eleanor McPeck]

Which is awesome and hilarious, and it’s become a part of Wesselmann’s own story, too. But. That nude in Great American Nude #44, modeled after the artist’s wife Claire, is hardly Marilyn Monroe. And with that actual radiator, actual coat, and actual telephone that was wired to ring every six minutes, this thing is more a multimedia assemblage than a “collage.”

And as for JFK, I know JFK. JFK was a friend of mine. And you, head of a woman cropped from a Renoir painting, are no JFK.

All Burliegh’s descriptions of supposedly scandalous elements–the sitting president leering at a reclining nude–actually match up to an earlier Wesselmann, Great American Nude #21, painted in 1961 [below]. But that nude looks even less like Monroe than #44, who, you could at least imagine just had her dress blown off by a steam grate.

As the luck of the market would have it, both of these Wesselmanns have been resold in the last few years. Great American Nude #44 sold at Christie’s in 2002 for $944,500. “The Popular Image” is listed at the top of its exhibition history. Then in 2007, the Abrams publishing family sold Great American Nude #21 at Sotheby’s for $4.1 million. But there’s no mention of “The Popular Image” at all. After a 1962 exhibit at Tanager, Harry Abrams bought the picture in 1963 and didn’t show it publicly until 1976.

A press release for the Sotheby’s sale [pdf] boasted about #21‘s controversy:

Demonstrating the potent power of Wesselmann’s imagery, the work was censored from a 1963 exhibition at the Washington Gallery of Modern Art reportedly because the image of the President and a nude appeared together, perhaps with the Marilyn-like lips, a loaded reference to Kennedy, and Monroe, who was recently deceased. Wesselmann wrote a letter to the editor of Art News in the summer of 1963 against the museum’s decision to censor the work.

So what really happened? Was #21 in “The Popular Image” show, only to get pulled after all? Did word of JFK’s pillowtalk intervention come too late, or only after the fact? Or was #21 the image bandied about when deciding on Wesselmann’s inclusion in the show, but it was never at risk of actually making it in? And was #44 ever at risk of being pulled from the show? The only thing I know for sure is that despite some rock-solid sources, the Washington Post never mentioned the issue–or Wesselmann’s participation in the show–at all.