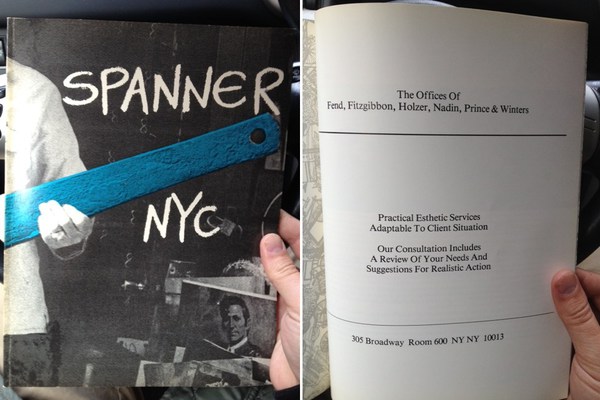

A couple of weeks ago at Printed Matter I found copies of Spanner NYC, an arts magazine published in 1979-80 by Colab folks including Dick Miller & Terese Slotkin. In the back of the third/blue issue was a full page ad from “The Offices of Fend, Fitzgibbon, Holzer, Nadin, Prince & Winters,” offering their “practical esthetic services adaptable to client situation.”

There’ve been a ton of shows related to Colab recently, and I’d known The Offices at least by name, or as a line in a few peoples’ CVs. As the recent creator of a corporate entity designed to operate in the art world, though, I guess I’ve been newly sensitized to such ventures. And I realized I had no idea what, if anything, The Offices actually did.

So first, the basics. The Offices seems to have been a conceptually driven, services-based, artist collaborative run on the ad agency or consultancy model. Which might be considered alongside corporate experiments like N.E. Thing, Co in Canada; Art & Language in the UK, that other UK group that infiltrated companies all over, which I can’t remember the generic name; and even the art-as-professional service work of Michael Asher. Or maybe it’s a failed utopic version of a massive sellout operation like Takashi Murakami’s Kaikai Kiki, Ltd.

The Offices sounds like it was an outgrowth of Colab, or at least created by artists involved in Colab. Peter Fend called it a “spinoff.” Here’s a photo from, perhaps, a board meeting, with all the name partners: [l to r] Robin Winters, Richard Prince, Jenny Holzer, Coleen Fitzgibbon Peter Fend, and Peter Nadin.

Actually, it could be at Peter Nadin Gallery, the artist’s studio transformed into an accretive exhibition space with Chris d’Arcangelo and Neil Lawson, where artists created work in response to the space and what had been made & shown there before. That continued for eight months from 1978-9, ending with a memorial show to mark d’Arcangelo’s death.

Or maybe it is the show on ecologically optimizing North America’s political and economic systems by reorganizing boundaries around its saltwater marsh basins. That show included work, a poster, by Fend and Holzer. I would have pegged Fend for the instigator of The Offices, but in telling the story of the basins project, Political Economies After Oil, he writes that Holzer “asked Fend to join her in a six-person artist team intent on “functional” projects.”

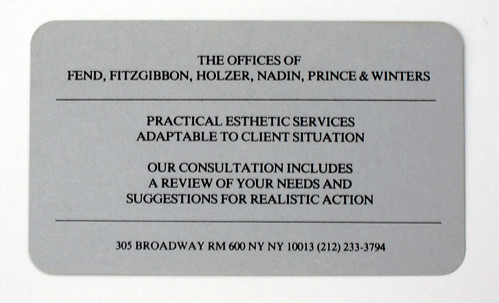

The Offices business card, via 6 Decades Books’ flickr stream

I guess it’s really the Colab/collab spirit. At least at first. Nadin was also collaborating similarly with Holzer at the time, producing artist books and text&image-based works. As Nadin describes it, “We took an office on Broadway and advertised our consulting services. This was great fun, but internal disagreement quickly turned the venture into a comedy. Art had become a farce. I realized this particular avenue of inquiry had come to an end.”

In a 2011 NY Times story pegged to Nadin’s wonderful show at Gavin Brown, Randy Kennedy got the sense that The Offices were “a mostly serious attempt to redirect the impulse to make useless art objects into some kind of socially helpful work for hire.”

Which sounds great, but unless they count keeping themselves from making objects as an achievement, it still doesn’t explain what they actually did. Richard Prince told Kennedy, “I think we were supposed to hand out aesthetic advice, but I was never sure. I thought we were supposed to play music. But we never played.” Which sounds about right for a professional firm in which Richard Prince is a partner.

One ambiguous project comes to light from Fitzgibbon, who was VP, then President of Colab during The Offices’ run, and was thus involved in both The Times Square Show and The Real Estate Show, installed without permission in an abandoned ConEd building on New Year’s Eve 1979. In a January 2013 interview she told BOMB that “[The Offices] approached the UN to offer our ‘function & pleasure’ art services for their labor problems. (They did not accept.)”

Not sure what that means. In a 1990 “Open Letter to Jenny Holzer,” Fend makes a reference to “campaigns pending with UN organizations and with the North-South commission of Willy Brandt, though envisioned, was ever undertaken.” Which I think means the vast study on the economic disparities between the Northern & Southern hemispheres known as the Brandt Report.

By its content, but also its timing, form, and existence, I think Fend’s “Open Letter” gives some insight into The Offices’ ambitions, conflicts, and its demise. 1990 was, of course, when Holzer’s US Pavilion won the Golden Lion at Venice:

2. Ten years earlier, in 1980, Jenny Holzer, Peter Fend and four other artists, including TV producer Colen Fitzgibbon [her pseudonym, used between 1979-80. -ed.], painter Robin Winters, then Holzer-friend Peter Nadin, and Richard Prince, were asked with some urgency by scientists at the California Institute of Technology to help develop an advertising campaign, or some such creative media campaign, in their capacity as “The Offices”, for promoting a scheme for replacing fossil fuels with a marine-biological source. Shortly afterwards, however, The Offices collapsed. No such campaign, nor other campaigns pending with UN organizations and with the North-South commission of Willy Brandt, though envisioned, was ever undertaken. Instead, art history took quite another course.

So for Fend, The Offices was a mashup of ecological urgency, international institutions, action on a global scale–and thwarted art history.

21. The art power and even outright media power of each of the members of The Offices since 1980 has been considerable, with one of those members becoming an official artist for the United States in 1990, so clearly the combined power of these five individuals–if they had stayed together on projects such as the one requested by Caltech and Global Marine scientists–would have been considerable, particularly in relation to the world image of the voice and policy of the United States.

…

23. From late 1980 through early 1981, Jenny Holzer maintained an [sic] proposal to work together with Fend and Fitzgibbon, along with a dozen other artists, in a company called Ocean Earth which was formed after the dissolution of The Offices, but the proposal was rejected. She had offered to be the media director for Ocean Earth. This was seen as threatening by the shareholders, given her already dominant recognition in the art world and her material resources. There have been voicings since then that this rejection was a serious mistake.

Interesting. in Fend’s view, at least, the Ocean Earth Construction and Development Corporation was the legal and corporate successor to The Offices. And he and the other “shareholders,” somehow perceived Holzer’s emergent art world success as a threat. Maybe not so much because of diverging priorities as because of Holzer’s practice, where her embodiment of the forms of corporate communications and control gained traction without relying on the fictions of corporate personhood.

If The Offices’ main accomplishment was to spawn Ocean Earth, that might be enough. The artist-run entity had a remarkable run as media analysts, image generators, and holders to the fire of the feet of companies and governments around the world. Their nimble diversion of satellite imagery helped break the stories of Chernobyl, and wars in The Falklands and Iran-Iraq. Ocean Earth gave its artist-shareholders and executives seats at tables that would otherwise have been unavailable to them.

The only catch was making a living. For a while, at least, Ocean Earth was able to take advantage of information arbitrage, quickly identifying, grooming, and repackaging satellite imagery to the very news media they were either seducing with scoops or critique-shaming into buying.

But The Offices’ value proposition seems to have based on exploiting common commercial interest between artists and their corporate/institutional clients. They hypothesized the existence of a monetizable deliverable their esthetic and ethical skillset could produce that was not, as Nadin put it, “a useless art object.” The best chance they had was probably the “media blitz” Fend alluded to: advertising and branding. And yes, though the dates seem a bit of a stretch, but in Andrew Russeth’s recent, excellent profile of Fend, we learn that The Offices deserves credit for the successful rebranding of 112 Greene St as White Columns.

To paraphrase Holzer, the failure to support six artists’ megalomaniacal attempts to alter the entire political and economic structure of the world by doing design work for a non-commercial arts space that got the boot from its free SoHo basement comes as no surprise.