Now that I’ve read up on it, and on the philosopher’s harrowing last days, I think I experienced the Walter Benjamin Memorial in Portbou, Spain the only way it really should be experienced: by total accident. Which is almost impossible.

We’d been visiting family in Provence, and one of the kids, the one who has been taking Spanish, not French, was wanting to go somewhere they spoke her language for a change. Plus, they wanted to go to the beach. Relenting, I pulled up the last town I knew in France, Banyuls, and looked to see what, if anything, was across the border.

The answer was Portbou. Google Maps said it was 3.5 hours away; we figured we’d drive to Spain for lunch and a couple of hours on the beach, send a postcard, and head home for dinner. Extraordinary traffic which had the autoroute backed up for several kilometers before the border, and the caravan of caravans winding along the 1.5 lane coastal mountain road, easily doubled our drivetime, and we arrived in Portbou starving and almost late for lunch.

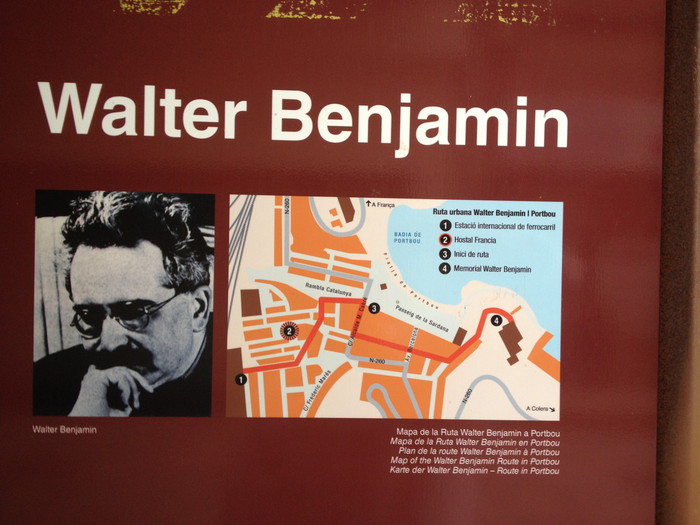

We quickly parked in a massive tunnel-turned-one-way parking lot, and wandered back through town to find any open cafe. And that’s when I spotted the Walter Benjamin information panel. It turned out to be No. 2 on the town’s four-stop Ruta Walter Benjamin, the Hotel de Francia, where Benjamin and his fellow refugees stayed after sneaking across the Spanish border in September 1940. And where he, where, well, as the panel puts it, “What happened over the next few hours is a striking illustration of all of the tragedy of barbarism.”

This town has erected a plaque in front of the hotel where Benjamin killed himself.

But there’s more. Three more. We passed panel No. 3, “Inici di ruta,” somehow, near the waterfront, and No. 4, the Memorial Walter Benjamin, was ahead. Typing this now, I see that these are ordered, not in relation to Benjamin’s journey, the path of which roughly mirrored our own, but for Benjaminian pilgrims, most of whom would arrive in Portbou via Barcelona at No. 1, the destination Benjamin himself never reached: the train station.

We found a restaurant on the promenade, Passatjes, still serving lunch, and sat down. It looked like the memorial was just on the other side of the harbor, set into the hill. So I began explaining who Benjamin was, and why our daytrip to the playa now had to include a visit to the memorial.

I knew the basics of Benjamin’s flight from the Nazis, with his fabled manuscript-filled suitcase, and his decision to kill himself when he felt his escape had failed. But I didn’t know any of the details, starting, obviously, with where it happened.

After lunch we went down to the beach, then around a cove, then back, and as we were getting ready to leave, I figured I’d jog over to the memorial while the kids dried off, and we’d go. It turned out to be a garbage can. So I had to ask around, and the nurse in the harbormaster’s office gave me a map that explains how the memorial is on the top of the hill, not the bottom. So we ended up driving. Up a one-lane, one-way road which dead-ended at the city cemetery [above]. The Memorial Walter Benjamin is, I guess, this plaza? the terrace? The plaque?

There is this striking Cor-ten steel-encased stairway descending to nothing over the water. Which is a memorial of sorts, Passages, designed by Israeli memorial designer Dani Karavan for the 50th anniversary of Benjamin’s death, but not actually realized until four years later, 1994. But Karavan’s intense sculptural experience is, according to the Benjamin quote etched into the glass midway down the staircase, dedicated to the nameless sufferer, not the famous. It feels designed to extrapolate or detach from Benjamin’s specific, complicated fate, to evoke the unknowable suffering of the unknown masses who have fled in fear. It felt, frankly, like a hedge. Maybe an accommodation to gather enough funding from German, Spanish, and Catalan sources.

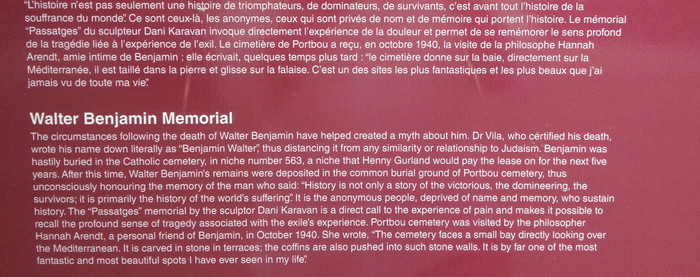

The information panels give a bit of the story of Benjamin’s burial in the cemetery, and again, complicated is my fallback term. There is a quote from Benjamin’s friend Hannah Arendt about how beautiful the cemetery’s site is, but not about how she had been unable to actually find Benjamin’s grave. In death, in Portbou, he became Benjamin Walter, a Catholic apoplexy sufferer, not a Jewish morphine overdoser. The burial niche which was leased for him for five years, number 563, seems to have been renumbered out of existence. [At least we couldn’t find it.] And though a large memorial stone now sits in a cemetery garden, Benjamin’s remains were apparently transferred, when his lease expired, to the town’s common grave.

Being the site of a famous fleeing philosopher’s suicide is a complicated tourist draw, made more difficult by Spain’s and Portbou’s own complicity in Benjamin’s death. It was the Fascist government’s sudden change of policy to return refugees to France that trapped Benjamin in Portbou. For many decades after the war, well past the end of the Franco era, there was no commemoration of Benjamin’s presence in Portbou at all. So what is there now, from the plaques, to the memorial to everyone, feels like an uncomfortable calculation, a threading of a memorializing needle. Benjamin’s no Jim Morrison, and Portbou’s no Père Lachaise. he’s too small a draw, and Portbou’s too remote, to ever have his death become an economically viable pilgrimage site. But he’s famous enough to some, at least, that something, they figured, must still be done. This might be a precursor for how memorials are going to develop in our YouTube niche microfame era.

The town’s official Benjamin Memorial website points to larger plans that didn’t pan out. An annual Benjamin conference is mentioned, though there don’t appear to be any updates since 2010. I imagine German philosophy offsites were one of the easiest line items to be cut by a small town grappling with Spain’s nationwide political and economic crisis.

But even before the recession, the accounts of people seeking out Benjamin’s history in Portbou are ambivalent at best. This excerpt from Michael Taussig’s 2006 book, Walter Benjamin’s Grave, about his 2002 trip to Portbou, is totally depressing, even though–or precisely because–he gets past the inevitable suitcase/manuscript hunt. David Harding’s account of visiting Karavan’s memorial and an anniversary ceremony in 2005 shows local authorities struggling with their weird historic/tourist legacy. This Haaretz recap of Benjamin’s last hours underscores his fatally bad timing; his group arrived in Portbou in a maddeningly narrow window–just a few days, really–in which the local political situation turned against him.

So if you’re ever in the neighborhood of the place the locals call “the end of the world,” I’d say go to Portbou. Eat at Passatjes, which was surprisingly wonderful. Ask what’s up with their name. And remember the cemetery is on top of the hill.

Or you can literally follow in the philosopher’s footsteps over the mountains from Banyuls by hiking the treacherous Chemin de Walter Benjamin. Those are your two best options.