I’m sure photomural historians out there are chuckling, wondering when I was finally going to catch up on this, but

HOLY CRAP, PEOPLE! ANSEL ADAMS PHOTO MURALS!

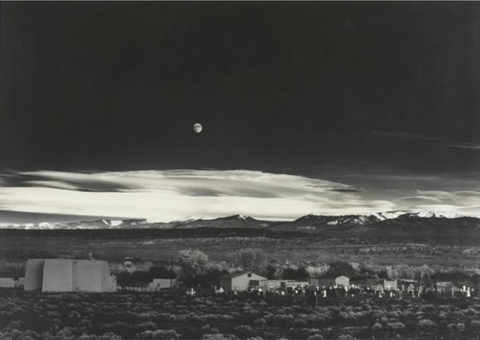

Alright, it’s not quite so unknown. The Polaroid ransacking auction last year at Sotheby’s included a very large print, what Adams called “mural-size,” of the photographer’s iconic image, Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico.

But The Mural Project was actually an Adams thing, a series of images commissioned by the Department of the Interior. Adams traveled around the US, shooting–he took Moonrise on the same trip, and because he hadn’t expensed that day, the photo was his, not the government’s. World War II derailed the project, though, and it was sort of forgotten. Until last year, apparently. When Adams’ original prints were rediscovered in a file somewhere [really?? looking into it. Hmm, this book of the images, which are now in the public domain, was published in 1989.], Interior Secretary Ken Salazar gave the OK in 2010 to install full-scale versions of The Mural Project for the first time. They’re still there, at the Interior Dept Museum. Viewing them requires a reservation.

Adams wrote an essay/letter titled “Photo-Murals” for the November 1940 issue of U.S. Camera [looking into it] in which he argued for large-scale prints, permanently mounted on panels, over wallpaper-style murals. He made such “mural-size” prints for the lodge at Yosemite, and for various exhibitions, but he also took orders for large prints. Most were smaller, around 40×60, but they did get bigger, up to 6×9 feet. The 2003 show of monumental Adams photos Andrew Smith Gallery spent ten years assembling included one such 6×9 print.

But not a screen. Because apparently Adams would occasionally make photo screens, giant prints on multi-panel, folding screens. Which, what?

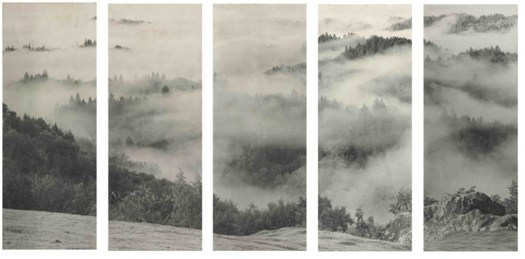

Clearing Storm, Sonoma County Hills, image via christies.com

He didn’t make very many, though; when they sold a big, awesome 1951 screen a couple of weeks ago, Christie’s said there were between 12 and 15, mostly in museums and the Adams Estate. Apparently, he sold one to Interior Secretary Harold Ickes in 1935, though, a deal which according to biographer Jonathan Spaulding, led to the Mural Project commission.

The screen he made for the Skirballs originally had an image on each side; the lot description says how when Jack Skirball invited Adams to come visit in 1981, they were “most anxious to have your opinion on what Audrey has done with the panels of the screen. I don’t want to tell you more until you see them.” It sounds like she remade them into a set of five one-sided panels. No word on what she did with the other image–or what Adams’ reaction was. Even so, the ex-screen sold for $242,500.

Though Adams was always very cognizant of the particular physical qualities of his prints, these screens seem to pose an entirely different argument for the concept of photo-as-object. If murals are related to frescoes, and “mural-size prints” evoke paintings, then Adams’ photo screens–printed to human scale, mounted in angled strips, freestanding in space, where they are intended to be viewed and experienced by moving around them–are akin to sculpture. Photographic sculpture.

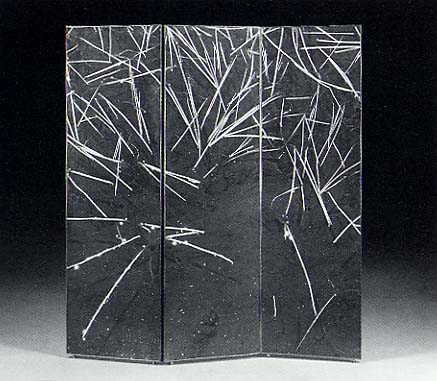

Or maybe they’re also sculpture. Because check out this one, Grass and Pool, a three-panel landscape photo and abstract action painting and freestanding object, all in one, and made in 1935. Oh wait, never mind. The image is from 1935, the screen is from the mid-50s. No need to rewrite the history of abstraction today. It was made for David McAlpin, a banker and collector who, as a trustee at MoMA, helped found the photography department in 1940.

Grass and Pool, sold in 2001 at Christie’s

Adams talked at length with Ruth Teiser about his photomurals and screens–actually, he talked at length with Teiser about everything; she recorded and edited 24 interviews with Adams between 1972-4 for UC Berkeley’s Regional Oral History Project, and later published the 818-page transcript as Conversations with Ansel Adams.

I transcribed some excerpts about photomurals from the Internet Archive after the jump. Adams’ main concern was the quality and character of large-scale prints, a topic which regularly veers into details of what an expensive, annoying, labor- and material-intensive pain in the ass it was to make good, big work.

[BEGIN QUOTES]

Teiser: You were mentioning large prints. I think I have read that the first mural size prints you made were for the San Diego Fair. Is that right?

Adams: Yes, the Yosemite Company ordered some prints from me for the San Diego Fair. And they advanced money to put in the darkroom in San Francisco so that i could do it. Never an entirely generous attitude. I mean I had to pay for it, amortize it over several years. But I did ge some fine large pictures made. Now I have a problem of getting some huge things for the Museum of Science in Boston, but I’m not going to do them myself. [Telephone rings]

Teiser: I took that opportunity to turn the tape. We were talking about photo murals. Would you ever have thought of making that huge print if you hadn’t had that specific order?

Adams: Well, just before the war, Secretary Ickes appointed me photo muralist for the Department of the Interior, with the idea that I would go around the national parks and make photographs which could be used as big mural installations. I never thought of making the prints; I just thought of directing the making of the prints.

Now we have to clarify something: a mural means something on the wall, and you paint a mural or a fresco. If you make a photograph and paste it on a wall, it’s probably the worst thing you can do because it contracts and swells and wrinkles and curls, and the wall settles and you have a series of catastrophes, and usually the adhesive you put it on is hygroscopic and makes it perfectly terrible–fading, etc.

So I make fine quality big prints limited in width to thirty nine inches. We do it in the form or panels. I did make one years ago that was 12 by 18 feed–a picture of Half Dome; I did it in sections. The sections were mounted on panels and put up like a double screen with dividing lines. It was extremely effective. It still remained a good print; it was not plastered on a wall.

The only good photographic paper is forty-inch width, and of course it’s impossible to process single-weight paper adequately; it’s so delicate, and the basic processing and adequate washing required would crack and crease it.

There’s an awful term called “blowup,” which just means an enlargement “without consideration.” Most photo murals are blowups. They’re pretty terrible. They’re usually toned (bleached and toned) in silver sulphide and come out an egg-yolk-yellow sepia [laughter], which is perfectly horrible but very permanent. That’s the reason it’s done. They’ve reduced the silver to silver sulphide, which it would naturally gravitate to if it wasn’t well processed, only it wouldn’t do it evenly.

I can make prints up to seventy-six inches high and thirty-nine inches wide. And I make screens–I’ve made five-panel screens and four-panel screens, but they have fine print characteristics. They’re not just blowups. And they’re also rather costly. It’s a terrible job. The large print is $2500 plus, and the screen would be about $10,000. It would have to be–

In making a screen you first have to make your dummy, you have to know just where to divide the image, and you have to plan the divisions so that when the screen is folded you don’t get a displacement of diagonal lines. You have also to consider frame and hinge space. It really is an awful job. Then you have to do it in the enlarger and scale it exactly to be sure you have the required “safe” overlaps. Then you have to plan carefully controlled exposure and use pretty big sheets of paper for tests to get just what you want. Then when you make the screen, you expose each section in sequence and you develop them, each one in a fresh developer, exactly under time and temperature control so that they will match.

And when that’s all done, you feel happy. You make at least two or three of the complete screens while you’re doing it. You tone them, and you have to be sure the toning is equal. Every time you put a section through a bath it has to be a fresh bath, so I’ll use up ten dollars worth of toning solution in making a screen. But, after all, time is the most important thing. And making big prints is very expensive and when you throw away–well, let’s say, every time I make a large print order for that Half Dome picture–say 30 by 40 inches–I would probably use an entire roll of paper.

Teiser: How much–

Adams: Well, it’s about thirty dollars.

Teiser: No, I mean how many–

Adams: Oh, I mught use up eight feet. The rolls come in 50 inches by thirty feet, or 40 inches by 50 feet. I can manage a 50-foot roll, but it “squeezes” my equipment. They make it in 100-foot rolls, but the trouble is now that Kodak and other manufacturers are restrictive. With certain items like Kodabromide rolls, you have to order at least $300 worth. You see, that’s what they call a restricted order. You can’t just go to the store and buy them–they ship to order from the factory.

…

Teiser: Back to the mural–Mrs. Eldridge Spencer told us the story about a large photograph for the Mountain Room at Yosemite. She said she wanted to crop the photograph in a way that you thought was entirely wrong, and she won!

Adams: She insisted on a detailed image of Sequoia foliage. She wanted it fifty inches wide, and I could only do it forty inches. So we had Moulin make the print, and Moulin charges so much a square inch and would never think of making two prints. And I told her, I said, “I’ll let Moulin do it, but it’s got to be a good print.” I think I insisted on three before he got it, and of course he charged for every one of them. And it added up–it was a big charge for a lousy job. She bought a group o twenty or thirty fine prints made especially for the room. Then there were some mountain climbing pictures made for the Boiler Room, which is a very good technical job–great huge climbing pictures. I don’t know who did those. I think General Grapic enlarged them. General Graphic did much better than Moulin.

Teiser: Do you make a photograph with the idea of its final size?

Adams: Oh yes, that’s the basic conceptual idea of what’s a photograph for. Now, I do a lot of work for Polaroid Corporation, and I always think in terms of 11 by 14 or of 16 by 20 from the Polarioid negative–4 by 5. I always try to thin, “Will this really enlarge? Can I make it?” I know that’s what they want. I mean, they have these great rooms and halls and they want pictures of that size. So I try to think of that.

Teiser: Most of the murals that you have made or that have been made from your negatives–were the photographs taken as mural photographs?

Adams: Yes, the ones for the Park Service, many of them were done with processing that was favorable to big enlargement. I guess I had one of the Grand Canyon that was going to be twenty feet high and fifty feet long. It never has been made. And then I’d done Coloramas for Kodak–sixteen of those things, which are twenty feet high and sixty feet long, in color. But of course those were all produced in Rochester. I used my 7 by 17 banquet camera for the color film. I had lots of fun. But large size is a conceptual matter. The best photograph in the world can be on 4 by 5; “blowing it up” to a big size might ruin it for both technical and aesthetic reasons. So I have people who say, “Well, I’d like an over-mantle of a certain picture.” I say, “You can’t have it; it won’t go that big.”

…

[Telephone rings]

Well, where was I? Oh yes–the photo mural. I hate that world. I simply say I make a large fine print, and it has to have fine quality and be absolutely permanent. To get that quality, there are many things that have to be overcome, like reciprocity effects, long exposures in the enlarger, and the extraordinary amount of handling these prints have to have. They’re developed and processed by rolling. You take a print six feet long and just roll it and adjust the development to give you five- or six-minute developing time. And it’s rolled back and forth maybe fifteen times and maybe five times in the acid stop and fifteen more times in the hypo and five times in the rinse, then goes back to ten times more in the plain hypo, and at least ten or fifteen times in the toner and at least six times in the hypo clearing, and at least five times rinsing, and then maybe twenty-five times in the washing. So ti’s a miracle that the print gets out without having breaks and folds. But it has to be done that way to be permanent.

Then it has to be carefully mounted.

[END QUOTES]

Ansel Adams, Conversations with Ansel Adams, pp. 375-9, interview XII by Ruth Teiser on June 30, 1972, published in 1978 by the University of California [viaarchive.org]

Previously, How to make a giant, Steichen-style photomural