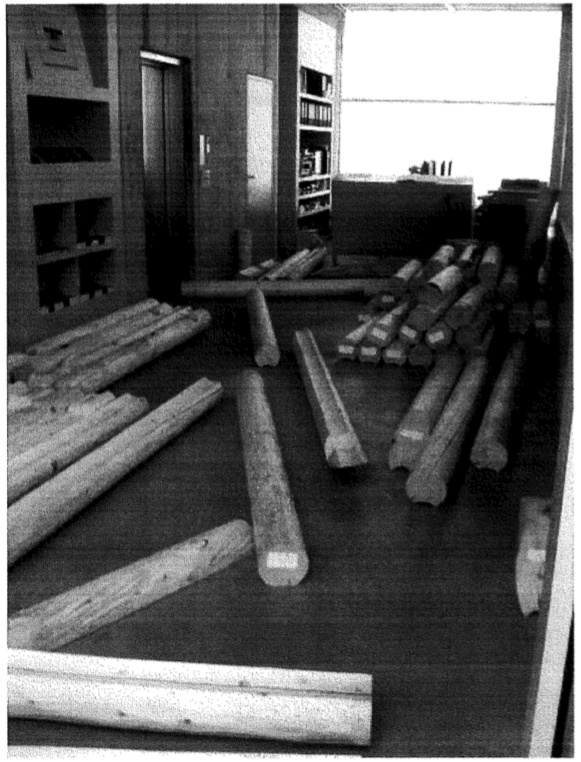

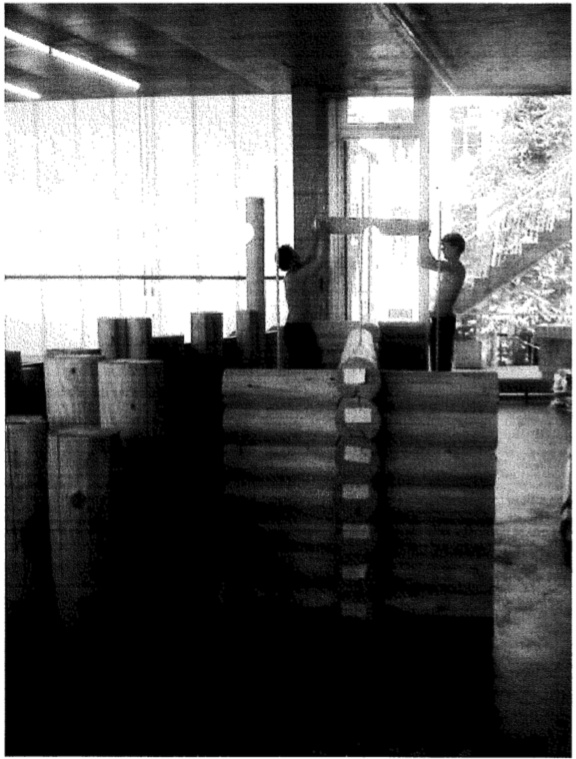

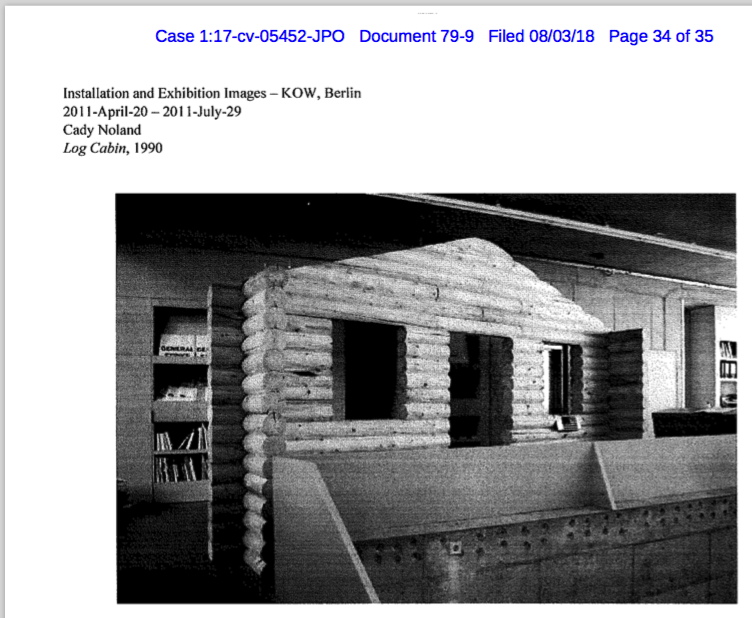

This is the first view of the log cabin formerly known as Log Cabin [actually, we learn, it was called Log Cabin Facade], a 1990 sculpture by Cady Noland, which the collector, Wilhelm Schürmann, left out in the mud for ten years, where it rotted, and then he had the whole thing refabricated without the artist’s consent or consultation, and then he flipped it, and the new buyer factchecked it, and found out the artist was very much not into it, and so he returned it, and had to sue for a refund, but got it. And during that whole process, no images of the remade sculpture [sic] ever surfaced.

But since then, Noland herself has filed suit claiming copyright infringement in both the US and Germany, and a violation of her moral rights under VARA, by the collector and dealers involved in destroying the original, and making and publishing and selling an unauthorized replica. And that lawsuit is where these images come from, from an exhibit in Noland’s attorney’s most recent memorandum [filing no. 79] arguing for the continuation of the case and against the defendants’ motion to dismiss it.

I’m reminded of this today because KOW, the gallery in Berlin where Log Cabin [sic] was unveiled in 2011, has a sleek, new website, with extensive documentation of the show–except for one, giant, contested thing.

The memo in the court case includes some other notable information, not least of which is a five-page affidavit by none other than Cady Noland herself. A sworn artist statement, if you will. It should go in the canon, so I have uploaded it here [pdf].

Noland talks of conceiving, designing, and realizing the artwork, Log Cabin Facade, in New York City “in or around 1990,” and traveling to Germany “to examine and approve the Work” as installed at Max Hetzler gallery. She “was not aware of the sale to Defendant, Wilhelm Schürmann, until August 1991,” she affirmed.

“Sometime around the mid-1990s…Schürmann sought permission to display the work outdoors…I agreed…At the same time Schürmann agreed with me the Work should be stained a dark color for ‘aesthetic reasons.'”

“At my request Schürmann had the work stained a dark shade of brown, I color I specifically selected and mandated. The stain [was]…basically a pigment, not a wood preservative,” the artist attests.

Noland continues to explain her expectations about Schürmann’s care for the work, which is the basis for her position about its damage, his its purported conservation, and refabrication. But these particular issues of timing and staining are important in new ways. They appear to this non-lawyer to be crucial to Noland’s invocation of VARA rights, which only apply to work made on or after the date the 1990 law went into effect, or which was made before the law went into effect, but which was only sold afterward. That date is June 1, 1991.

“Oh, the timeline sounds complicated and possibly contestable!” you say. It is not. Or rather, it is not important, because Log Cabin Facade is not Log Cabin Facade, but Log Cabin Facade (2). In the memo, Noland’s attorney explains that, “When the original natural wood color of Log Cabin was stained dark, Noland created a derivative version of the work,” which is “fully protected under [VARA].”

So Schürmann bought Log Cabin, which became Log Cabin Dark Shade Of Brown For Aesthetic Reasons, which he left outside to rot, and then threw into the wood chipper after replacing it with a brand new log cabin facade made in the (unpigmented) style of the original Log Cabin, which copyright and VARA he and his dealer friends viol–no, it was the original work’s copyright but the derivative work’s VARA. (Doesn’t the derivative get its own copyright?) What happened to Log Cabin [below] when Noland had it stained into Log Cabin DSOBFAR? Was it destroyed? Are we now bereft of two Log Cabins, with only the current log cabin, which is either a “refabrication,” a “reproduction,” or “a copy [that] was not authorized by Noland,” aka, “a forgery,” to remind us of our loss(es, which we didn’t know we’d lost until now?)

But no, this is not about you or me, but about the artist, whose work suffered neglect and destruction at the hands of those entrusted with its care, and whose wishes and intentions no one seemed interested in finding out until someone’s $1.4 million was on the line. The artist who now has “a gap in her artistic legacy” because “the original Work is no longer a part of [her] artistic body of work.” To which I would add, sadly, neither is the derivative.

And while there are many possible artistic strategies for authorizing, reauthorizing, declaring, or reconceiving the Work and preserving or increasing the Value in ways that many people, with much experience and insight, would be all to happy to elaborate upon, the simple fact remains that it the artist’s call, not theirs.

“I said the provenance for the sculpture must now include the name of the conservator because the work was not mine alone,” said the artist in her affidavit. Also, “I feel very strongly that the unauthorized copy of Log Cabin robs my Work of a quarter century of history and denigrates my honor and reputation. The Log Cabin that I created does not exist.”

Noland is actively pursuing a lawsuit that makes an affirmative argument about her work and her artistic decisions that confronts cultural, market, and legal presumptions of what art is and what an artist does. And here at the end of this post, I’m deciding maybe it’s more interesting to consider the implications of Noland’s actions as they stand rather than to game out scenarios for her like an armchair lawyer–or an armchair artist.

Social Violence, Cady Noland & Santiago Sierra, 30 April – 29 July 2011 [kow-berlin.com]

Previously, related: Why Wasn’t Cady Consulted?

Attributed to the Cowboys Milking Master