It’s weird to see a work of art without knowing the artist, and then to find out it’s by someone you know. The familiar overtakes the novel or, in the case of Publicon Station I, the lmao baffling. As soon as this gold leafed oar with a blue light bulb in its belly, standing in a geometric fabric-lined rhomboid cabinet was identified as a 1978 Robert Rauschenberg, its obviously a Rauschenberg, and from the 70s.

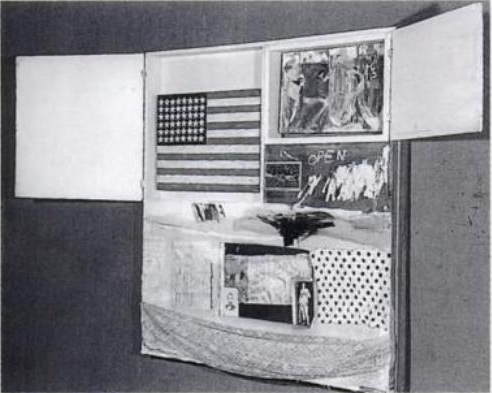

Publicons are a series of six wall-mounted sculpture editions Rauschenberg made with Gemini G.E.L. “Related to the Stations of the Cross”, the Rauschenberg Foundation explains, “the Publicons are cabinets, each of which opens to reveal an enshrined object. The title merges ‘icon,’ a reference to medieval reliquaries and Renaissance altarpieces, and ‘public,’ since sculptures can be manipulated by the viewer. “

Those religious references are all distinct, of course–stations, icons, reliquaries, altarpieces–and don’t neatly map to Publicons. My guess is Rauschenberg was not hung up on dogmatics of symbolism, narrative, or procession, &c.; he was going for a vibe.

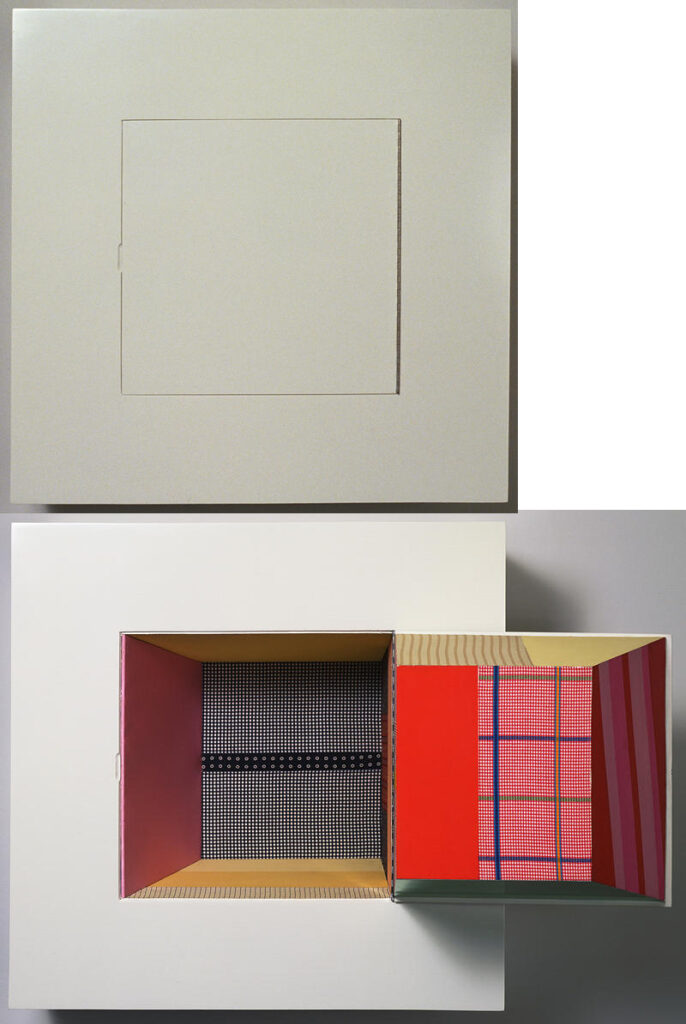

There’s a common vocabulary of beige auto lacquer on the exterior, and geometric fabric panel collages on the interior. Three have lights: I, IV and V. Four have objects “enshrined” in them. The gold leafed oar feels the most religious; the mirror, wheel and dangling brick are all found in Rauschenberg’s earlier work. (Of course, what isn’t?)

18 x 36 x 8 in. closed, images via NGA

Though their 1978 exhibition at Castelli Graphics did get a review in Artforum, not much seems to have been written about Publicons. Rauschenberg had bigger shows, and bigger work–and lots of it. In Artforum, Leo Rubinfien, always hard to please, wrote:

The central device with which the “Publicons” work is the difference between their blank and unyielding exteriors and their exuberant contents. Since they are modeled on icon cases, a hint of the sacred still adheres to them, reinforced by their individual titles—Station 1, Station II, etc. Thus one approaches and opens them a little cautiously, to find a crazy Pop/Surreal confusion inside. They are, in fact, as much jack-in-the-box as icon: Station I, when opened, reveals a canoe paddle covered with gold leaf, with a glowing blue light for a navel—it is as if the piece has stuck its tongue out at one for treating it respectfully.

I think a good part of what the “Publicons” are about is this mockery of their own audience of culture-lovers.

If it’s irony one seeks, one should look at the outside of the Publicons, not the interior. These aggressively blank, glossy boxes feel like a comment by Rauschenberg on an academic minimalism, deadpan sculpture with roots in the gestalt materialism of folks like Robert Morris or Donald Judd. The interiors of Publicons are exuberant in comparison to anything except other Rauschenbergs. They feel like the artist trying to relate, if not assimilate, to the art of his time.

Most reproductions of Publicons show only the most “interesting” part: the inside, and usually only one work. I wanted to see what could be seen by putting all the Publicons on one page, open and closed, in order, the way you might find them in a church gallery.

The Publicons contain as many references to Rauschenberg’s own work as they do to any religious mode. But maybe that misses the point; why couldn’t they instead reveal the reliquarian and altarpiece vibes of earlier combines, works where holy relics hide behind cabinet doors.