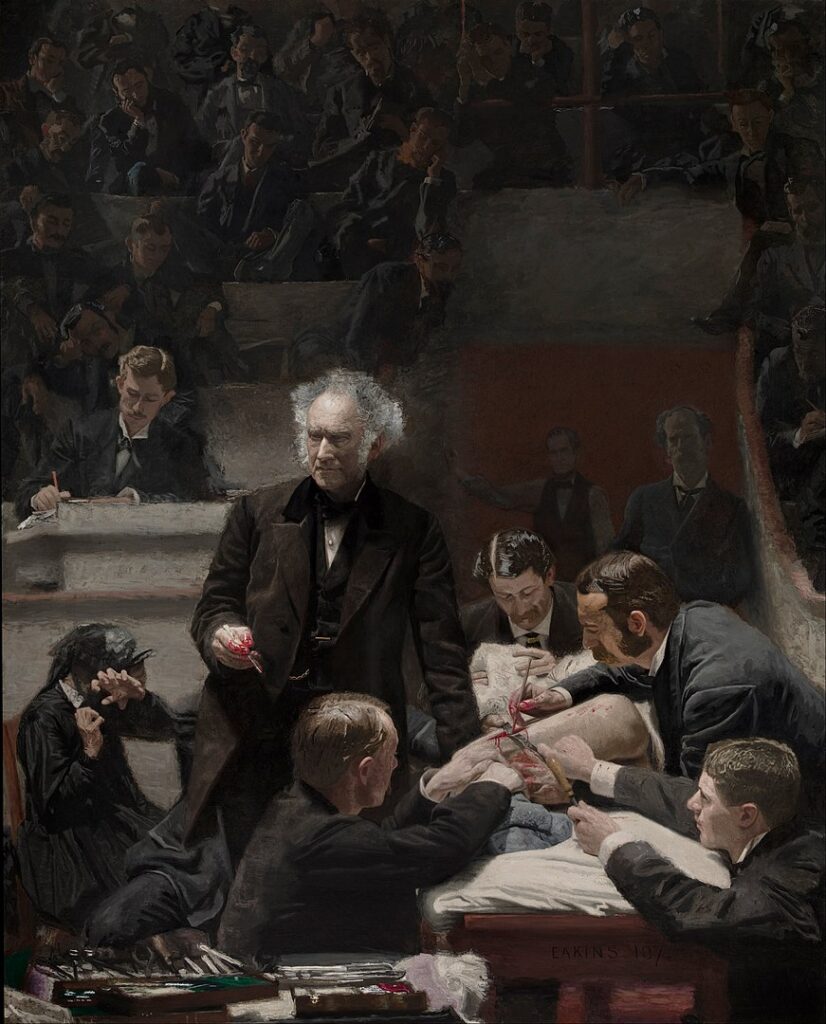

I’m not the biggest Thomas Eakins fan, but I did live in Philadelphia, so I’m at least familiar. I confess, I hadn’t really given him or his work much thought since his 1876 masterpiece, The Gross Clinic, was the target of Alice Walton’s surreptitious Crystal Bridges acquisition spree in the mid 2000s. With the help of her secret art adviser, National Gallery of Art curator John Wilmerding, Walton scouted out the most important works of American art held by institutions who were financially vulnerable, indifferently managed, and/or unbound by professional museum ethics–and then she bought it in a flash. It was a shock tactic that worked–until it didn’t, in Philadelphia.

Walton’s agreement to pay $68 million for The Gross Clinic to Jefferson Medical College, where it had hung for over a hundred years, was announced in November 2006. The painting would be jointly owned by Walton’s Crystal Bridges and Wilmerding’s National Gallery. Within weeks, the city, its museums, its politicians, and its donor class rallied to keep The Gross Clinic in town. The Philadelphia Museum and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, where Eakins taught, ended up owning it together.

None of which has anything to do with anything, really, except that The Gross Clinic was such a controversial painting when it was made, with a combination of scientific innovation and gore-as-naturalism, that it made the scandals over Eakins’ nude models in co-ed classes seem tame by comparison. It’s always felt like the most serious work Eakins ever made, uptight, even, and so different from the self-consciously carefree homosociality of the Swimming Hole or whatever. Even though both complicated paintings, full of figures, were so closely linked to photography for their meticulous compositions.

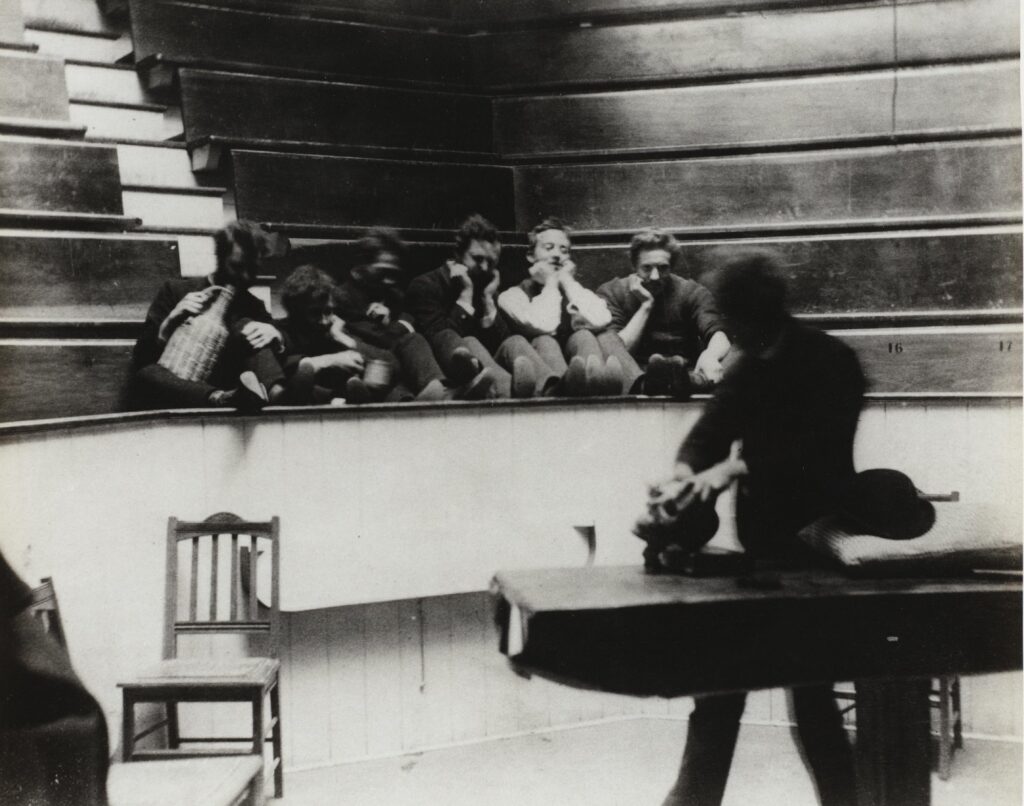

So it was a trip and a half to stumble across not just one photograph, but two, titled Parody of ‘The Gross Clinic’, in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum this morning. Here, at the very moment of The Gross Clinic‘s realization, are Yung Eakins and his posse, in the operating theater, goofin’ for the camera. They’ve got their feet up, passing the jug. They’re recoiling in mock horror as they pretend to dissect each other. There’s a frivolity and energy that I don’t see in the hundreds of Eakins photos in the Academy’s collection.

Again, what I don’t know about Eakins could fill several books, but these feel like exceptional Eakins objects. It’s interesting to consider how they came into the Philadelphia Museum’s collection. The parody prints–including one printed later from the 1875-76 negative–were donated by George Barker in 1977. A George Barker, Junior also donated an unusual Eakins object, a small nub of turned, painted wood, like the sawed off end of a broom handle, which carries the title, Egg. Prof. Michael Lobel tweeted it out this morning, noting its sleek, proto-Brancusian form.

It dates from 1884. Barker, Junior dated from 1882, and he died in 1965. I assume he’s related to Professor George Barker, who was a prominent chemist and public intellectual at the University of Pennsylvania when Eakins painted his portrait in 1886. Did Eakins give young Barker Egg as a gift? How did it leave such an impression on Barker that before he donated Egg to the Philadelphia Museum, he made two facsimiles of it, and donated them, too?

There’s a story there, of how and why George Barker, Jr. ended up with a trove of weird Eakins stuff, and I hope it gets told. Anyway, today was Eakins’ birthday.