From a link from Visible Darkness, an engrossing, intense weblog about a book project to examine documentary photography. (wonderful, but not for the blurb-addicted):

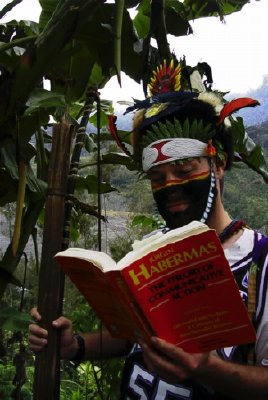

In one week on grad student Alex Golub’s weblog, he writes the good fight, assailing the academically-descredited-yet-still-pop-consciousness-gripping “anthro” brand/icon Margaret Mead; laments the lonely life of the actual Pynchon reader (achingly different from a “fan”), and recognizes the painful poignancy of the Oklahoma! revival in these “September 11”-besotted times. All well-written, but again, don’t think you can just skim the site while you put that conference call on mute.

Golub’s recap of Mead criticism hits home, especially since Mead (and by naive extension, anthro) was one of my first stops on my idealistic foray into filmmaking. Mead’s legacy: “Systematically and symptomatically bad fieldwork in which she gave up what she knew about the people she lived with in order to paint a picture that would fit in with the message she attempted to get across to the public.” (Fortunately, I was early swayed by the Maysles brothers’ “just show what you see” storytelling and their sense of fidelity to the people they lived with. Mead hasn’t really turned up here since.)

His analysis of his Gravity’s Rainbow Problem speaks for itself:

6) What you really want out of this party is not the free martinis or interesting gallery space or recognition that you are one of the people being published in the glossly lit-mag whose latest issue is the raison d’etre of this fete. What you want is to find someone, just someone (preferably an alto, although a strong colatura soprano or even a decent bass-baritone wouldn’t be too bad either) who has also read it and understands what it is you’re trying akwardly to express nine minutes into your five-minute monologue…

As for Oklahoma!, he casts an anthro/cult stud (I made that one up based on “anthro”; I’m sure it’ll bring in some interesting Google searches) eye on the musical’s “condensed symbolic account of the founding impulses of the United States of America.” Homogeneity and pacification figure strongly in his analysis, which isn’t as optimistic about the London revival others have praised for being darker and more ambivalent than you remember it from high school drama club.

While I hope he hasn’t fallen into the pit where he sees Mead (I haven’t seen Oklahoma! ever, even though I’m working on a musical now), his message in the end sounds too good not to be true:

It is not surprising that Oklahoma! should be playing on Broadway at a time when the radical uniqueness of the US’s project is more than ever obscured by a shallow, partisan patriotism. Nor is it surprising that the recuperation of the founding impulses of the United States seems so unlikely.

‘What have you given us?’ a man asked Benjamin Franklin as the delegates of the Constitutional Convention ended their secret meetings. ‘A republic,’ he said simply, ‘if you can keep it.’ We have been given a unique country and a valuable ideal. And we are turning it into Oklahoma!.