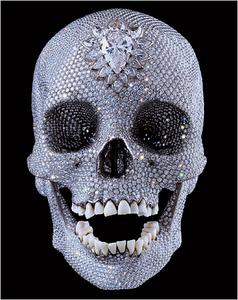

First things first: if someone DOES buy Damien Hirst’s diamond-and-platinum skull, it won’t be for $100 million. Any shlub billionaire walking in off the street would get 10% off, and any actual collector would get 20%. So if someone’s been around the art block already, that’s where he’ll start talking.

Second, by floating a $20 million cost figure, Hirst is taking a page–and a number, even–from Christo’s playbook that likely has more to do with setting a context for potential buyers than with the actual outlay.

Hirst told the Times, “The markup on paint and canvas is a hell of a lot more than on this diamond piece.” but the difference is far less than it first appears.

8,160 diamonds but only 1,100 carats, those are some small stones. A quick glance at the Rapaport Report will tell you what dealers would pay for 1,000 carats of 0.125 carat D-F stones. [0.23 carat D IF stones are $4,900/carat retail on BlueNile.com. Comparable 0.5c stones are double that, so let’s assume comparable 0.125 stones are half, or $2,500/c retail.] Depending on how far back along distribution chain Hirst was able to reach, the actual cost–or if you’re cold about it, the actual “value”–of his diamonds could be a half, a third, a quarter of that.

Diamonds, it turns out, are a lot like art: heavy on perceived, light on actual, value. They’re are no more or less intrinsically valuable than dead flies, another medium Hirst has employed for his art. The only difference is the cultural assumptions of decadence or disgust attributed to them [and given the bloody, terrorist- and tyranny-funding origins of so many African diamonds, decadence and disgust aren’t mutually exclusive.]

Apart from their subjective value, then diamonds and art share an aura of exclusivity. Which turns out to be almost entirely artificial as well. Diamonds have been historically rare because of their geographical concentration and the difficulties in extracting them, but the DeBeers cartel has also manipulated the supply and perceived scarcity of diamonds for over 100 years.

Even as diamond stocks from beyond DeBeers’ direct control have entered the market, it remains in dealers’ and suppliers’ economic interests to maintain the DeBeers-created industrial and distribution system–and margins. But those monopolistic days are numbered.

In 2003, Wired reported on two companies who were developing technologies to manufacture flawless diamonds for use initially in jewelry, but the real goal is to revolutionize the semiconductor industry by making diamonds economical enough to replace silicon. From there who knows how cheap diamonds could become?

Before mass production techniques were developed in the 1890’s, aluminum was a rare and precious substance, too. For example, in 1858, Charles Christofle made an extravagant centerpiece from aluminum for Emperor Napoleon III’s Chateau de Compiègne. By the turn of the century, aluminum was being used for luggage. Now I have an aluminum centerpiece decorating my table: a pyramid of empties made for me by Diet Coke.

If there’s any significance at all to Hirst’s skull, it’s as a symbol of a far-reaching, manipulative cartel of dubious ethics at the center of an elaborately collusive web of mutually beneficial delusion. Whether that’s the diamond market or the art market or both, as subjects go, it’s not bad at all.

On the bright side, Hirst may be onto something in his quest for museological immortality after all, even if our grandchildren are paving their driveways with diamonds a hundred years from now. By employing master craftsmen with royal warrants to create an object of superlative, if fleeting, value, an object that has been the subject of religious, artistic, and cultural interpretation for millennia, and an object that doesn’t take up even a fraction of the vitrine space of, say, a tiger shark in a tank of formaldehyde–Hirst may have guaranteed that at least one piece of his art will be shown in a museum a hundred years from now.

Update: Hirst suggested the British Museum would be a good spot for his skull. A reader reminded me that the British Museum is the home of the Crystal Skull, which was a controversial hit in the Age of Aquarius [ie., the Seventies]. That’s when no less an authority than Leonard Nimoy suggested the only way the Mayans–or was it the Atlantisans?–could have carved it 3,600 years ago was with extraterrestrial help. Turns out it was manufactured in Germany in the 19th century. And like all the world’s Crystal Mystery Skulls, it originated with a French art dealer in Mexico named Eugene Boban.

If the British Museum is looking to deepen their holdings of shiny, over-hyped skulls made by charlatans that lie irrelevant and forgotten within thirty years, Hirst may be in luck. Then again, judging by the similarities between the Museum’s photo of the Crystal Skull and Hirst’s own images, it looks like that was his plan all along. And he’s only out a couple million pounds to pull it off? Brilliant.