Let me get this straight: the first modernist prefab in the US; one of two US houses included in Phillip Johnson’s 1932 International Style exhibition at MoMA [the other: Neutra’s Lovell House]; built in 10 days from off-the-shelf industrial materials, with no formal plans or blueprints; Albert Frey’s first US project; bought and disassembled in hours, then saved and bastardized by Wallace K. Harrison; quoted nearly perfectly–concept, materials, and form–by Kieran Timberlake in their Cellophane House; and yet somehow Aluminaire House itself was not included in “Home Delivery,” MoMA’s 2007 show on the history of the modern prefab Please tell me I just missed it or blocked it from my memory.

But I’m hardly the only one.

Lawrence Kocher was editor of Architectural Record and later involved with Black Mountain College. The 27-year old Albert Frey was fresh off the boat from Le Corbusier’s studio. They whipped up Aluminaire House from donated parts and materials for a 1931 building show and Architectural League exhibition at Grand Central Palace, an expo hall that filled the block between 46th and 47th streets and Park and Lex.

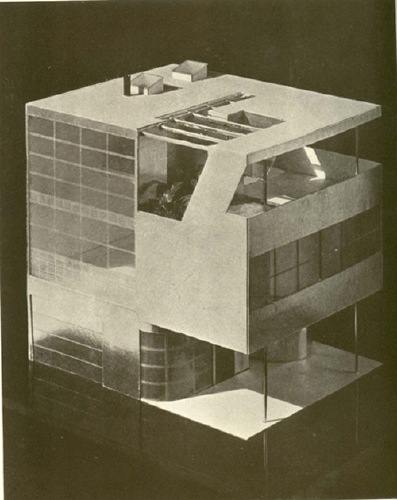

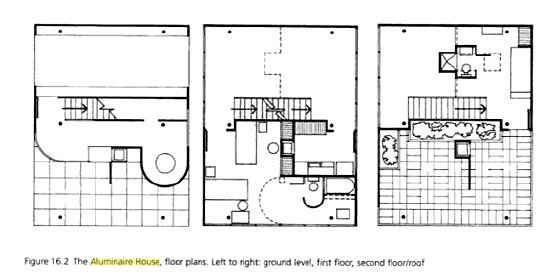

Kocher’s concept was a light-filled, modernist prefab house made of innovative, industrial, mass-produceable materials: aluminum, steel and glass. The 3-story, 5-room, 28×22-ft, 1,200 sf building was barely more than a mockup, an exhibition pavilion. Frey later compared it more to a refrigerator than a building in its construction; it was light steel bolted together with nuts and washers and skinned in ribbon windows and corrugated aluminum, a material Frey would use extensively in California. The floor was ship decking covered in linoleum. Interior walls were rayon fabric. It was supported on five aluminum pilotis.

The main living space [LR/DR, Kit, MBR, BA] was on the second floor. The living room was double height, open to a partially enclosed library/2nd bedroom on the third floor, which also had a terrace. A second bathroom with shower was cantilevered over the living room, which frankly sounds like a joke.

Harrison bought the Aluminaire House for a thousand dollars after the expo ended, and reassembled it at his house on Long Island. In ’32, Johnson showed the house in the International Style exhibition, but didn’t include it in the catalogue. Harrison proceeded to enclose the ground and third floors and add on some circular structures, rendering the house nearly unrecognizable.

Which is why it was almost demolished in 1987-8 when Harrison’s estate was chopped up and developed. The architecture department of the New York Institute of Technology took the Aluminaire House on as a school project. They studied and dismantled it, then eventually reassembled and restored it on a new pad on their Central Islip campus. Which looks to be about 10 minutes south of Exit 55 on the LIE, within easy pilgrimage visiting by every design snob in the Hamptons.

And yet, no one really seems to care or know about it. In a brief blurb about a 1998 Arch. League show on restoring Aluminaire House, Herbert Muschamp got the location and story of the house wrong. No one who writes about it sounds like they’ve actually seen it. There aren’t any contemporary photos of it online, only one shot from Harrison’s yard.

It’s on Google Maps, of course, and that’s Microsoft’s Bird’s Eye view on the right. But no mention of it on NYIT’s site. [The architecture department was moved from Islip to a campus in Old Westbury, so if it served any academic purpose before, the Aluminaire House seems kind of orphaned now. A 2007 messageboard post said that it was to be relocated as part of a redevelopment/selloff of part of the campus. If it hasn’t happened yet, I’m sure it won’t happen for a while.

But it sounds to me like there’s an unloved, unappreciated pile of historic modern awesomeness in the middle of Long Island that needs to be liberated and returned to loving domestic use. At the very least, will someone take half an hour on the way to the beach and go shoot some freakin’ photos?

The only lengthy discussion of Aluminaire House I can find online: docomomo’s 1998 Modern Movement Heritage by Allen Cunningham [google books]

Skip to content

the making of, by greg allen