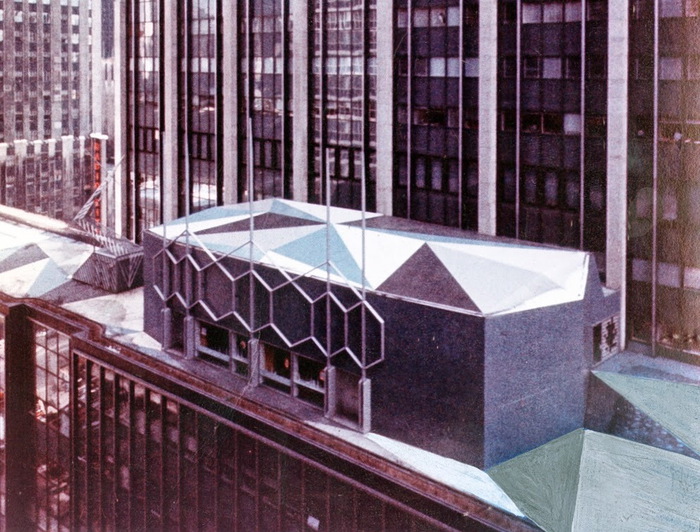

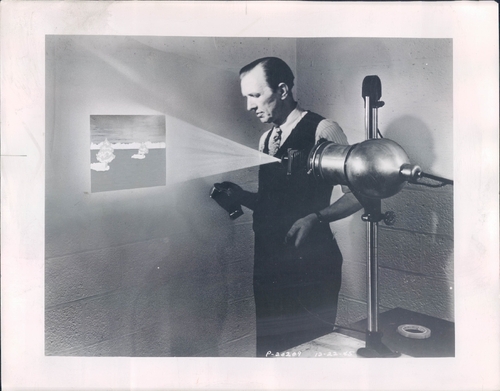

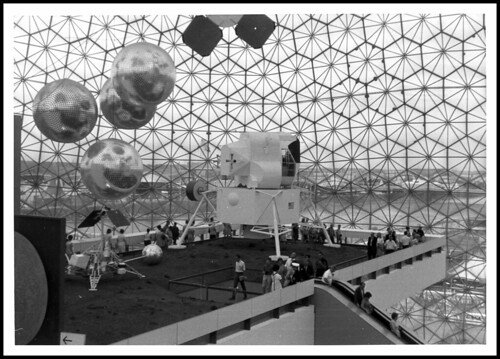

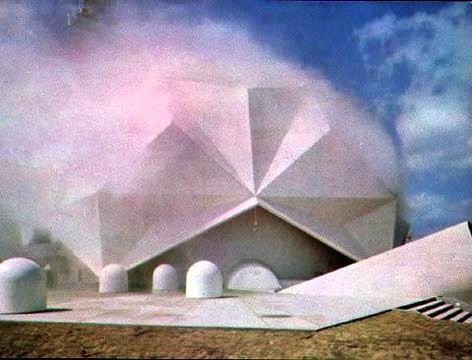

Photomurals in the 1900-1918 section of Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900-1968, Metropolitan Museum, 1969, image: The Met

It’s been a while since I’ve written about them, but photomurals still have a wide, quasi-artistic place in my heart. And so it’s great to run into them in the most unexpected places.

Like in Holland Cotter’s story of seeing the Met’s botched attempt at racial appeasement, the 1969 exhibition, Harlem On My Mind.

I knew the show was controversial, and that black artists had rallied against it and similar flawed, tokenist shows in the works at the Whitney. But I never knew what the Met actually showed: basically, no art, just 2,000 photographs. Which, to the Met, in 1969, were emphatically not Art.

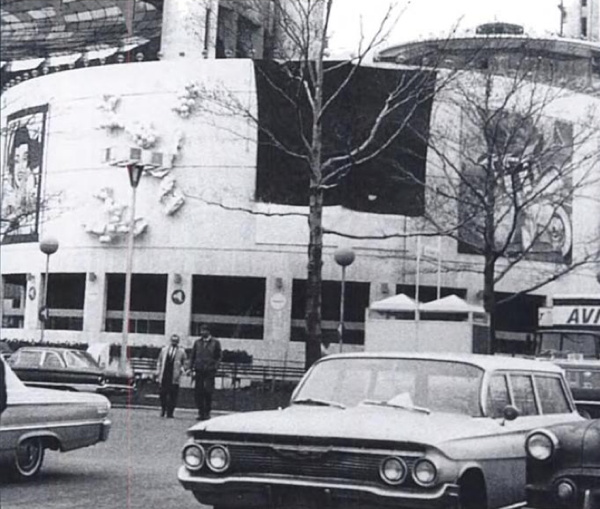

Which is not entirely fair. The show was conceived by the Met’s hot new director Thomas Hoving, a former NYC Parks Commissioner who had been known, as Life magazine put it, as a proponent of “be-ins, love-ins, traffic-free bike rides, Puerto Rican folk festivals, and happenings.” Harlem on My Mind was seen as a way to make the museum relevant to African American audiences, but also to bring the stodgy institution into the contemporary cultural discourse.

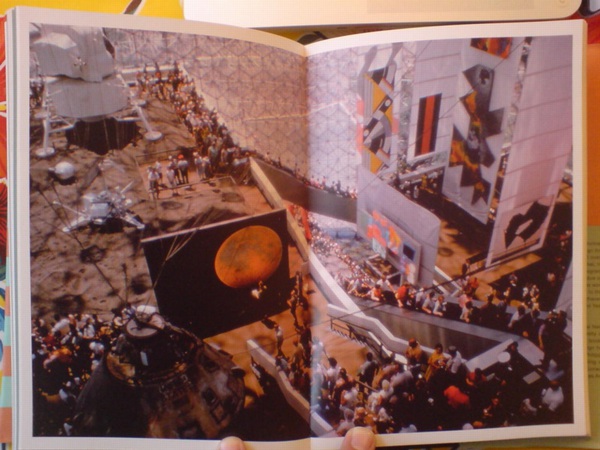

The show was curated by Allon Schoener, and designed by Harris Lewine and Herb Lubalin, who basically tried to remake their popular 1967 Jewish Museum show, Portal to America: The Lower East Side, 1870-1925, but for Harlem, circa 1900-1968. The show was explicitly didactic, a one-hour experience immersed in what Bridget R. Cooks, in her 2007 study of the exhibition, “a multi-media extravaganza.”

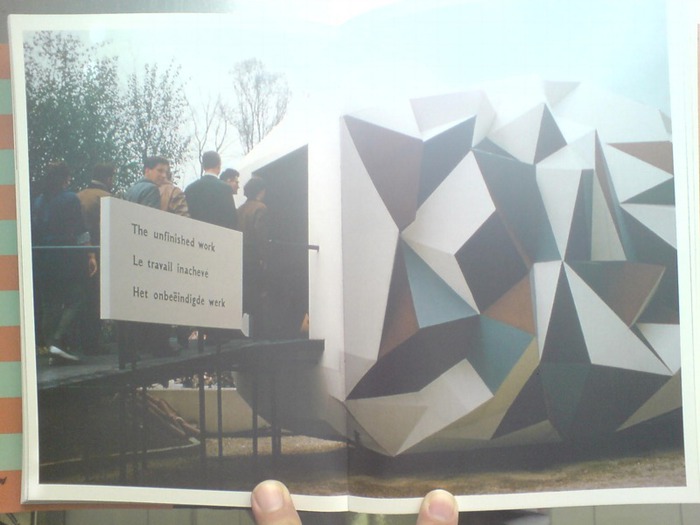

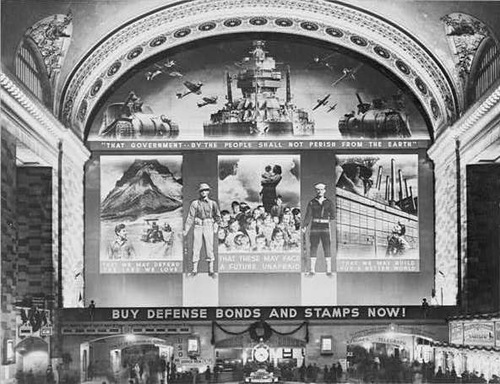

In this sense, it hearkens back to World’s Fair pavilion modes, or the immersive photo exhibitions of Edward Steichen-era MoMA, including the WWII shows and, obviously, Family of Man. Never mind that Roy deCarava and Gordon Parks, who’d actually been included in Family of Man, boycotted Harlem on My Mind, and then mobilized against it.

Anyway, the point is, there was a context for this show, several contexts, in fact, including for how the exhibition was designed, and what the experience of it was intended to be. And those contexts, especially the activism and protest the show engendered, have displaced the content and form of the show itself. The content was a paternalistic, problematic mess, in so many ways a failure, but the form was apparently successful–and is now lost and mostly forgotten.

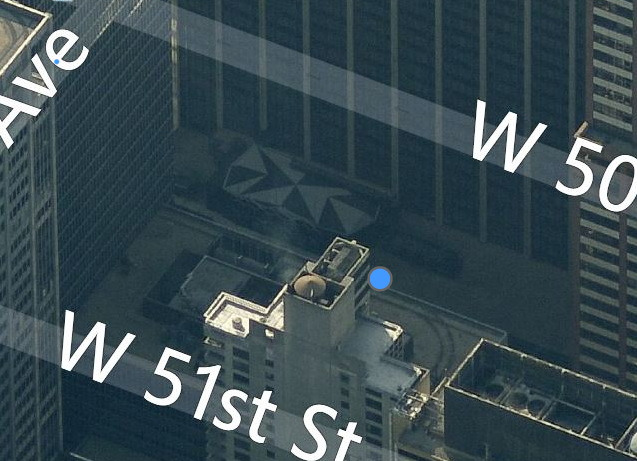

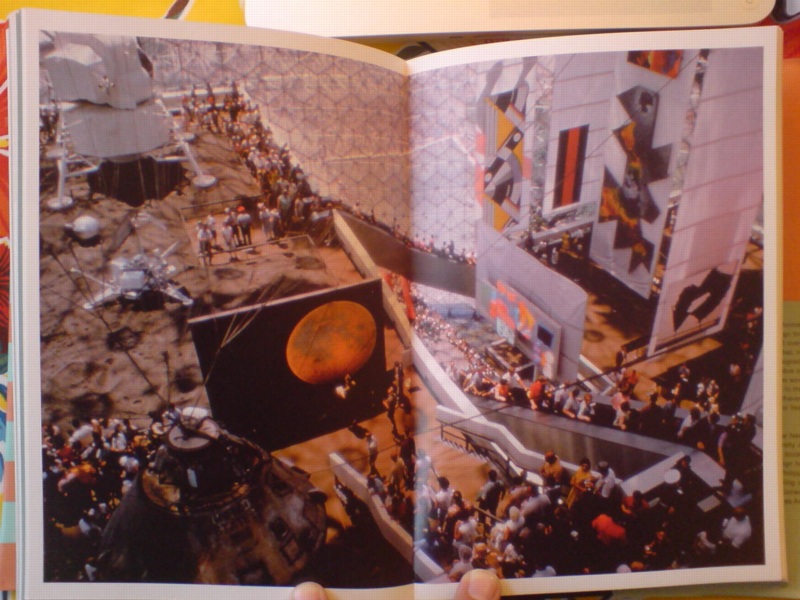

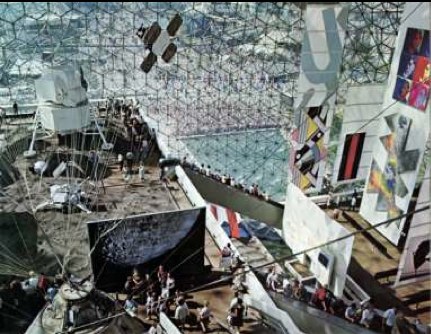

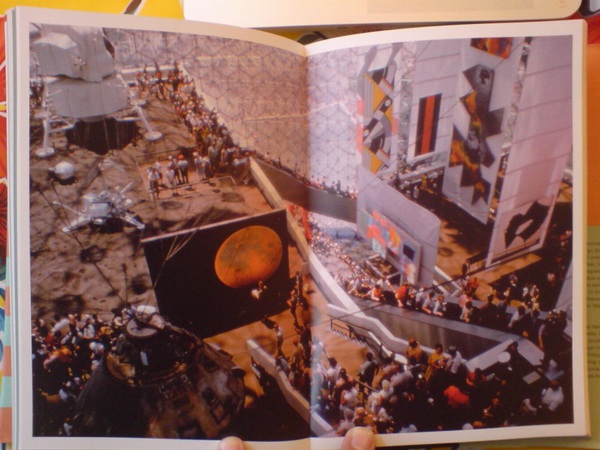

phenomenal photocube totem columns in Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900-1968, Metropolitan Museum, 1969, img: The Met

phenomenal photocube totem columns in Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900-1968, Metropolitan Museum, 1969, img: The Met

Here are some of Cooks’ descriptions:

Various wall layout designs were used throughout the galleries to display more than 2,000 photographs. Some walls held large-scale black and white photomurals eighteen feet in height and of varying widths.

…

Some walls were used dramatically as dark screens for projected images of Harlemites and street scenes from slide projectors suspended from ceiling tracks. Four-sided columns displayed photographs of Harlem buildings, streets, and residents in both formal portraits and informal community scenes. Some columns, topped with large photo-text cubes, stood over ten feet high in selected galleries as if they were free standing sculpture. Several of these towers highlighted notable Harlem figures such as elder resident Alice Payton “Mother” Brown and Billie Holiday in their respective decade galleries.

Speakers camouflaged in large cylinders, hung throughout the galleries, delivered Harlem street sounds and music to visitors. Films and videos were interspersed through the galleries to provide further information, and a closed-circuit television showed the real-time activity at the intersection of Seventh Avenue and 125th Street in Harlem. Photographs punctuated with text were suspended from the ceiling to create billboard-like visual timelines that marked important national events, such as the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, 1954. The exhibition was designed to provide a one-hour experience for each visitor. [emphasis added for awesomeness, awesomeness, and lol srsly?, respectively.]

Though some art critics bailed, calling the show sociology, not art, Grace Glueck weighed in:

To this viewer, there is something terribly American about “Harlem.” It panders to our penchant for instant history, pack- aged culture, the kind of photojournalistic “experience” that puts us at a distance from the experience itself. Instead of the full, rich, Harlem brew, it presents a freeze-dried Harlem that does not even hint at flavor.

Harsh, but admit it, the Harlem-cam had it coming.

Anyway, I want to make these photototems now, or rather, see them exist again. I’d hope not, but I think they’d be all kinds of problematic all over again if I made them. I just hope they could exist again, as the alluring, outraging failures they were. Because they do feel terribly American to me, too, and terribly New York. I think a trip to the Met’s archives is in order.

What I Learned From a Disgraced Art Show on Harlem [nyt via @JenGraves]

Bridget R. Cooks, “Black Artists and Activism: Harlem on My Mind (1969)”,

Amer. Studies, Spr. 2007 [pdf floatin’ around on project muse, go get it! oh wait, blackcontemporaryart has a clean link and the abstract all ready]

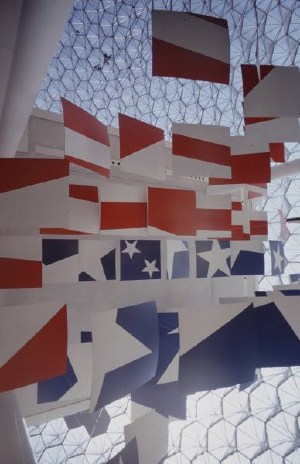

phenomenal photocube totem columns in Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900-1968, Metropolitan Museum, 1969, img: The Met

phenomenal photocube totem columns in Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900-1968, Metropolitan Museum, 1969, img: The Met