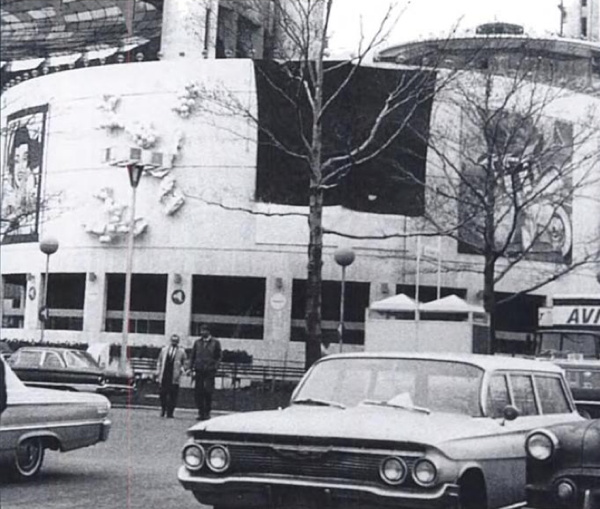

Thirteen Most Wanted Men overpainted and covered by tarp, 1964. Photo: Peter Warner, via Richard Meyer’s Outlaw Representation

From the amount of attention it gets, you’d think Andy Warhol’s 13 Most Wanted Men was the biggest art deal at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. And it wasn’t even there for more than a couple of days.

But there was actually other art in the fair, and organizer Robert Moses was not into it. Countries could show art if they wanted, of course–Italy brought Michelangelo’s Pieta, and Franco’s Spain brought some El Greco. But Moses rejected petitions for a dedicated art exhibition at the fair, and he intervened in at least one other situation besides Warhol’s to nix art that attracted criticism. I’ve dug around a bit in the New York Times’ coverage of art and the fair, mostly from the cranky conservative critic John Canaday, and it has broadened and definitely complicated my view of the era, the venue, and the outsize parties involved.

If you do nothing else, read Canaday’s various acidic takedowns of the consumerist banality and kitschy circus of the World’s Fair, and how Art shouldn’t even be mentioned in the same breath. His column, “The Fair As Art,” tries to stretch the definition of folk art to cover the what we’d now recognize as late capitalist spectacle, and it’s interesting how he can’t quite get the nascent Pop Art movement to sync up with the populist source of its content.

No, first read about Canaday’s Feb. 1964 evisceration of the announcement that Tomorrow Forever would be the “theme painting” the Hall of Education. The landscape was filled with the trademark Big-Eyed Children of Walter Keane, the Thomas Kinkade of his day, who, it turned out, couldn’t paint a fence, and instead passed his enslaved, abused wife’s paintings off as his own.

This extraordinary profile of Margaret Keane in The Guardian yetserday led me to Canaday’s review. [Tim Burton’s biopic of Keane comes out in a couple of weeks.] But the piece also says that “Stung by the review, the World’s Fair took down the painting.” Actually, Tomorrow Forever never made it into the fair. Robert Moses intervened almost immediately after Canaday’s attack, more than two months out from the opening, saying, “The fair does not censor exhibitions except in cases of extreme bad taste or low standards. This was such a case.”

[Ouch. Moses’s willingness to boot one reviled painting makes his central role in the Case of the Destroyed Warhol Mugshots seem all the more plausible. For his part, Warhol praised Keane and his outsized commercialism. LIFE Magazine asked Warhol about Keane in 1965: “It has to be good,” he said. “If it were bad, so many people wouldn’t like it.”]

Anyway, Warhol’s World’s Fair piece can’t have been too much of a surprise. Though his name is misspelled, “13 Wanted Men” is mentioned by title in a NYT report from October 1963, “Avant-Garde Art Going To Fair”. The other nine artists Philip Johnson commissioned are also listed, and I realized I never registered that Ellsworth Kelly had been involved. But he produced a work on painted aluminum.

And here it was. Untitled at the time, Kelly’s 18-foot curves projected from the wall of the New York State pavilion, where they were installed next to James Rosenquist’s mural, which was next to Warhol’s. Except the Rosenquist is either covered or gone in this Nov. 1966 photo from World’s Fair enthusiast Randy Treadway. So is Robert Indiana’s EAT, which was on the right of Kelly.

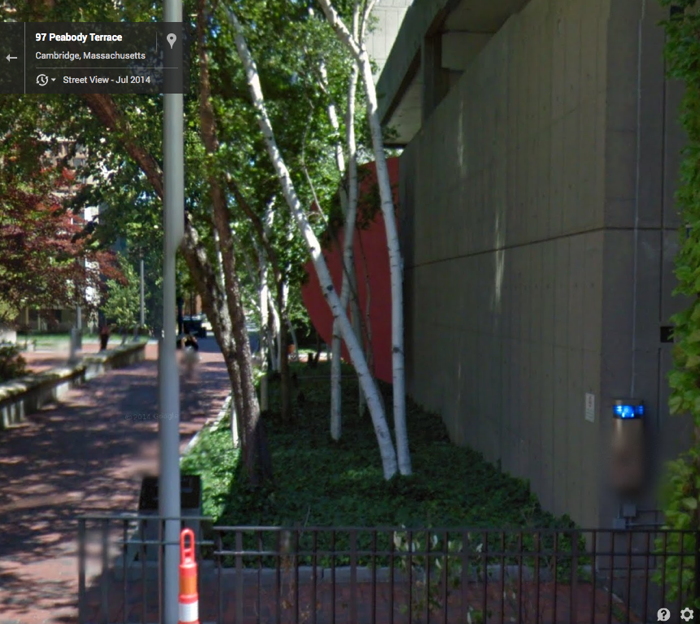

A bunch of the NYS Pavilion pieces ended up in the Weisman collection at UMinn., but in 1967 Johnson apparently donated the Kelly to Harvard, where it was known as either Two Curves or Blue Red. In 2001, a campus-wide survey of culturally important objects found “Blue Red” on the side of the parking garage at Peabody Terrace. The super was about to repaint the deteriorated sculpture with Rust-o-leum when conservators intervened. The Google Streetview image from this summer [above] shows it looking much better.

Skip to content

the making of, by greg allen