First I stumbled across this 1943 photo of a giant Olmec head at the National Geographic Society.

Then the caption says it’s actually a cast of the 20-ton original, which remains in La Venta, Mexico, where Dr Matthew Stirling (kneeling) led the NGS-Smithsonian expedition to document them. Stirling was the leading anglo archaeologolist working on the Olmec, a civilization that pre-dated the much better-known Inca and Maya.

Then while I tried to find out more about casting a 10-foot head onsite in the middle of World War II (turns out the head was one of five uncovered on a 1940 expedition), I stumbled upon Luis M. Castañeda’s extraordinary essay from 2013 for Grey Room, a journal at MIT Press. Castañeda tracks the history of exhibiting Olmec megalithic heads in the modernist North, and their shifting political, aesthetic, and ideological contexts.

Olmec megaliths were shown in the early 1960s at the Petit Palais in Paris; the LA County Museum of Art; the Museum of Fine Arts Houston; the Mexican Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair–with a pit stop on the plaza of the Seagram Building.

Castañeda tracks the equal interest in the megaliths as exoticized artifacts and engineering mysteries, and how they were experienced, in spectacular motion, temporarily installed in high modernist spaces. Here’s folks discussing the most epic way to transport an Olmec head from its original site in Veracruz, Mexico to the new Mies van der Rohe-designed museum in Houston:

Before they decided to use a trailer, [documentary filmmaker Richard] de Rochemont and [MFAH director James Johnson] Sweeney considered other options. In a June 19, 1962, letter, for instance, de Rochemont wonders whether a helicopter could get the job done more efficiently. In making this suggestion, de Rochemont also makes explicit that the real point of the project was not Figure 5 the head itself but the spectacle of its motion. “I estimate that ‘your’ head,” he writes to Sweeney, “weighs 15 tons… . Biggest known helicopter … lifts 10 tons … Would [Mexican authorities] mind if we cut the head in half?” Although the artistic and archaeological value of the Olmec head was of importance to Sweeney’s exhibition, in de Rochemont’s words, the visual documentation of the massive head’s movement was what truly transformed the film and the exhibition into “an archaeological epic.”

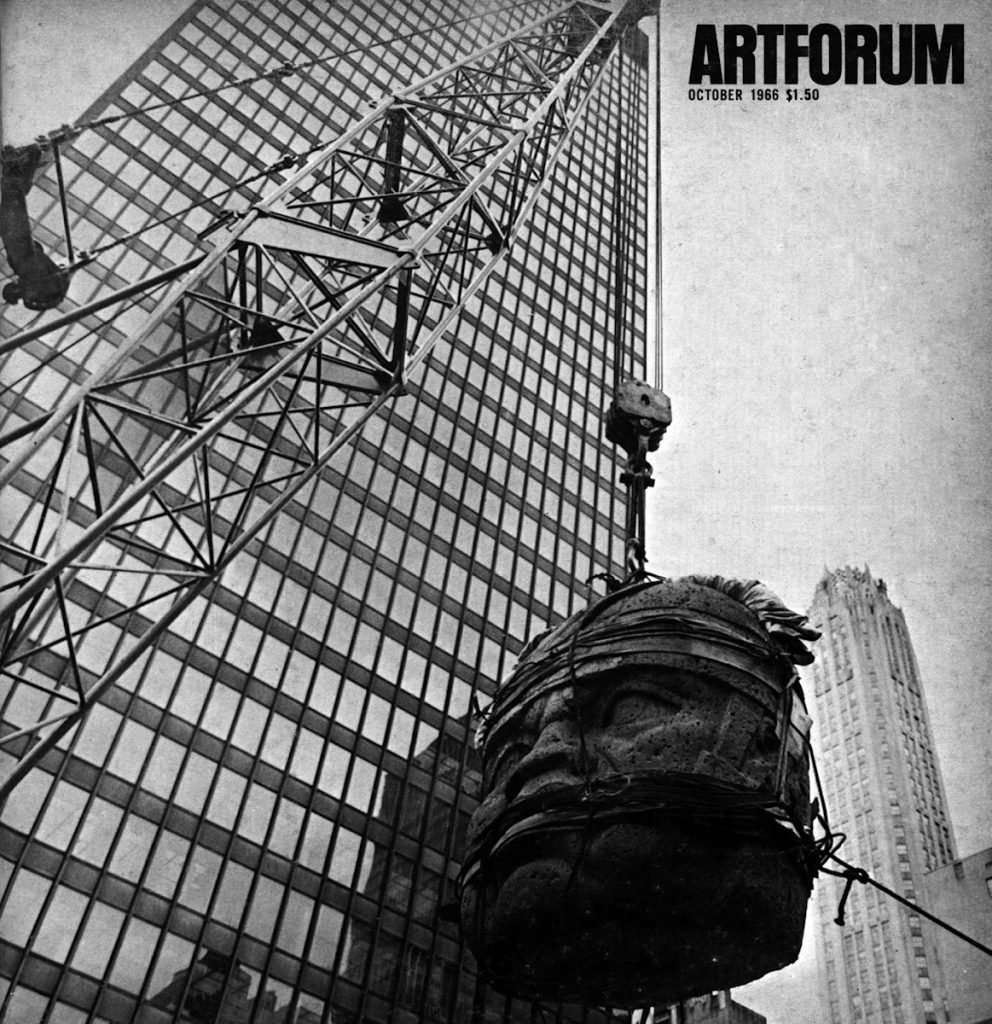

Also here is one of two Olmec heads being installed on Seagram Plaza, on a base designed by Philip Johnson, on the cover of Artforum, where Irving Sandler writes of the impact of the head on contemporary sculptors.

Most stunningly, Castañeda notes, that almost no one has looked closely at these Olmec sculptures, their genesis and impact, on the work of land artists like Robert Smithson or Michael Heizer. Heizer’s father Robert was a protege of Stirling, one of two US archaeologists who established Olmec studies as a distinct field. By the 1960s Heizer the father had left his research on Olmec engineering techniques and had begun helping his son excavate artworks in the Nevada desert. When LACMA opened Renzo Piano’s Resnick Pavilion in 2010, it was with a show titled, Olmec: Colossal Masterworks from Ancient Mexico, which featured two megalithic heads on cor-ten steel bases designed by Michael Heizer.

Doubling Time, by Luis M. Castañeda [greyroom, spring 2013]