Continue reading “Such Coup. Many Unconstitutional. So Thwart.”

Category: scott sforza, wh producer

FBI White (2025)

The FBI’s stated Core Values are

RESPECT

ACCOUNTABILITY

LEADERSHIP

DIVERSITY

COMPASSION

FAIRNESS

RIGOROUS OBEDIENCE TO THE CONSTITUTION, and

INTEGRITY

or at least they were.

Now I honestly can’t decide if this guy is making a subtle shoutout to fellow government worker-turned-painter George Bush, or if the new FBI Core Values is WHITE.

Either way, it’s unfortunately an early candidate for painting of the year.

Previously, slightly related? An unrealized proposal by Jacob Kassay to paint over an ‘overly celebratory’ photomural of racist federal government resegregator Woodrow Wilson at Princeton

Lutz Bacher, Untitled, 2017

Connecting The Dots

Reading Travis Diehl’s e-flux journal review of Arthur Jafa’s show at 52 Walker led me to Diehl’s road trip report in x-traonline of going to Cady Noland’s 2019 retrospective at MMK Frankfurt with Rasmund Røhling.

Which led to the recordings of the Cady Noland symposium convened at MMK on 27 April 2019.

Diehl also noted to Røhling that the Charlotte Posenenske sculpture and the Claes Oldenburg bacon soft sculpture included in the Noland show were very World Trade Center Twin Towers-coded. Also not to be a conspiracist or anything, but a Noland sculpture was also included in Peter Eleey’s September 11 show at MoMA PS1 in 2011.

Which led me to go searching for which Noland it was, and it of course, was the stanchion work, The American Trip (1988), which is more ambiguously political than MoMA’s other significant Noland, Tanya as Bandit (1989).

But none of that matters right now, because in looking through the installation shots, I was immediately sucked back in time by Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ black-bordered stack of mourning surrounded by Jeremy Deller’s “Mission Accomplished” banner.

And that banner. 90 x 600 inches, it was obviously a full-scale recreation of Bush White House image maker Scott Sforza’s hubristic aircraft carrier banner from 2003.

But I never made the connection to its title or date: Unrealized Project for the Exterior of the Carnegie Museum, 2004-2011. So Deller wanted to hang this banner on the outside of the museum as part of Laura Hoptman’s Carnegie International, which opened in October 2004, just before the presidential election. How far along did this proposal get, I wonder? [Deller ended up showing war re-enactors on tiny televisions inserted into the Carnegie’s dollhouse dioramas, the diametric opposite, attention-wise, from a 50-foot banner.]

The Arc of This McDonald’s Banana Milkshake Is Short

And it bends toward Nigel Farage’s face.

[image detail from Ben Stansall of AFP/Getty’s sublime triptych of an activist nail art aficionado dousing Farage with a large banana shake from the McDonald’s in Clacton-on-Sea]

Happy Pride [In A Still-Functioning Legal System]

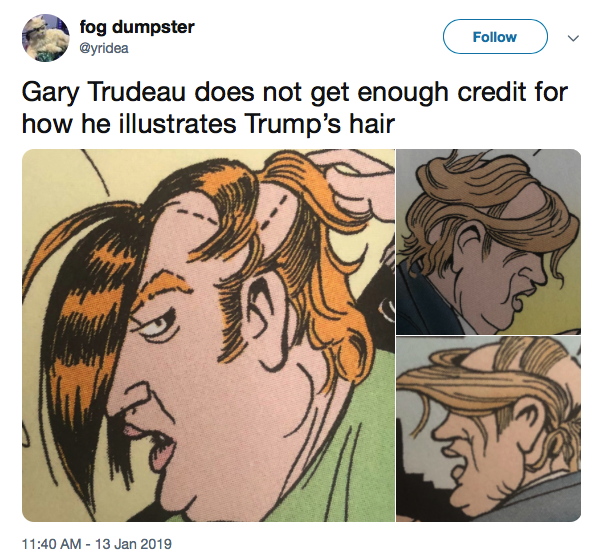

New York prosecutor Joshua Steinglass presented as evidence of Trump’s routine coverup and document fraud a falsified invoice for a shell company created to hide a different $125,000 hush money payment as an “Agreed upon ‘flat fee’ for advisory services.”

I post it here for the same reason Bump posted it at the Post: to praise Michael Cohen’s choice of clip art. It is a distorted rendition of 3-D Bar Graph Meeting, a stock image created by Scott Maxwell of Lumaxart. A version of it created on Christmas Day 2007 was uploaded the next day to flickr.

Though he’s moved his operation to Shutterstock, one of Maxwell’s last updates to his blogpost blog, The Gold Guys, was from 2017: a unified quorum of rainbow stick figures expelling a gold-plated wannabe king, and the word IMPEACH.

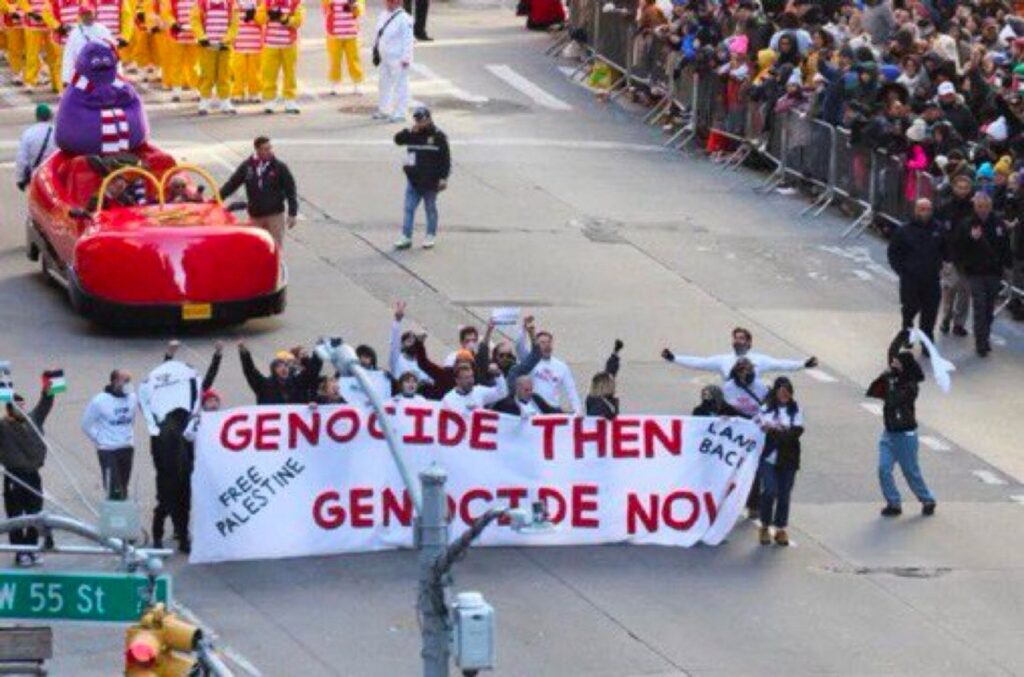

From The River To Macy’s

There are many, many images from the last few weeks that will haunt us for a very long time. But some hit an entirely different frequency, like Brandon Wilner’s photo, above, from the Macy’s parade.

Or the images of Writers Block intervening as an IOF contractor paraded down the Wickquasgeck Trail.

Look at his face, Grimace was clearly stunned, and is probably rethinking some things rn, under the menacing eye of 60-foot inflatable Ronald McDonald.

The George W. Bush Norman Rockwell Adolf Hitler Memorial Library

The Washingtonian notes that in addition to Supreme Court justices, Harlan Crow also collects Hitler paraphernalia. And yet Hitler manages to be only the second most shocking painter in this billionaire’s group show:

“I still can’t get over the collection of Nazi memorabilia,” says one person who attended an event at [Clarence Thomas’s billionaire Harlan] Crow’s home a few years ago and asked to remain anonymous. “It would have been helpful to have someone explain the significance of all the items. Without that context, you sort of just gasp when you walk into the room.” One memorable aspect was the paintings: “something done by George W. Bush next to a Norman Rockwell next to one by Hitler.”

Still more data for my 2017 assertion that George W. Bush is the most relevant painter of our cursed era.

Related: a 2017 Washingtonian article about the US Army’s collection of seized Nazi art; a breezy 2002 Washington Post article about the market for Hitler merch, including the Texas millionaire with a passion for The Austrian Painter’s paintings, no reason, he just thought they were neat

Previously: “Our Guernica, After Our Picasso”

“As he explained to Jay Leno, the idea of taking up painting comes from Bush’s fantasy of being, or being compared to, Winston Churchill. Churchill painted. Of course, Hitler also painted. If painting makes Bush like Churchill, does it make him like Hitler, too? Is either association, when based on painting, more or less outrageous than the other?”

Proposte Momacron

Some might say this warrior president Golden Room mise-en-scène feels like a very special Continental episode of Black Mirror come to life. Me, I say, that’s no black mirror: it’s a Proposte Monocrome Macron! Srsly, though, the Struth fan who took this photo deserves a Légion d’Honneur.

UPDATE WTF: I just zoomed in to make myself an Ellsworth Kelly-style rhomboid crop, and it appears that is not a flatscsreen TV with a reflective image on it at all, but an image? Non, but it is a picture. It is a Soulages.

Sforzian Spread

In early 2017, an editor I admire greatly asked me to write about the new aesthetic of presidential propaganda, a topic which has been a staple of this blog since White House advance man Scott Sforza transformed the September 11th attacks from Bush’s first great failure into his greatest pivot…for his even more devastating failures.

Anyway, point is, I was so traumatized by and angry at and afraid of what was coming, and how inadequate the standard tools of media critique felt, that I stumbled for months, and then ghosted them, and only too late apologized for failing to put this administration under the Sforzian lens. But of course, by then, we were all in it, and what was happening and what happened have indeed outstripped the norms we operated under.

And now here we are. At the pandemic, and the international crime, and the white supremacists, and the fascism, and the police violence, and the camps, and the deliberate destruction of government and public, and the fraud, and the religious extremists, and the armed vigilantes, and the elections, and now back this morning to the pandemic.

And here is a Reuters photo by Tom Brenner, taken at a campaign event in Jacksonville, Florida last week, which @corrine_perkins, @tomwhitephoto, and @brookpete daisychained into my Twitter feed this morning. It feels worth introducing into the flow of Sforzian imagery, but its impact is entirely of Brenner’s doing, not, obviously, its subject’s or his handlers’.

Max Mara Whitey Bag

Max Mara created the Whitney Bag in collaboration with the Whitney Museum’s architect Renzo Piano to echo the facade of the new downtown building.

To celebrate its 5th anniversary, the cult bag has been revived in a special edition version dedicated to the American painter Florine Stettheimer who boasts an important presence at the Whitney. A feminist and activist ante-litteram (1871-1944), Stettheimer’s work “Sun”, created in 1931, inspired the bag’s five new color variants and the design of the floral printed lining. [via]

Nevertheless when she needed a Whitney Bag to carry a bible across a tear-gassed public park for her father’s photo opp, Ivanka chose white.

Because of course it is, the tear gas police fired to clear peaceful protestors out of the park was manufactured by Defense Technologies, which is owned by ex-Whitney trustee Warren Kanders.

McDonald

via @maggieserota

It’s been like ten minutes and this photo is already blowing up twitter I will probably delete it soon because I just

update: I just could not.

Realized

This weird practice I’ve been exploring leaves me very aware of how I discuss it, and of how works are explained. I try to be accurate about what I actually do, or what a work has to do with me. A lot of times, the work exists, and I announce it. Or I’m stoked to announce it. It’s on view. It is available. Sometimes it is conceptualized. Rarely is it conceived; that doesn’t feel like how it works. It’s not really found, though that is obviously part of the process. Same with declaring it, though I bridle at the ostensible ease, which can make me doubt myself as a Duchampian poseur, or an armchair usurper of someone else’s creative exertions.

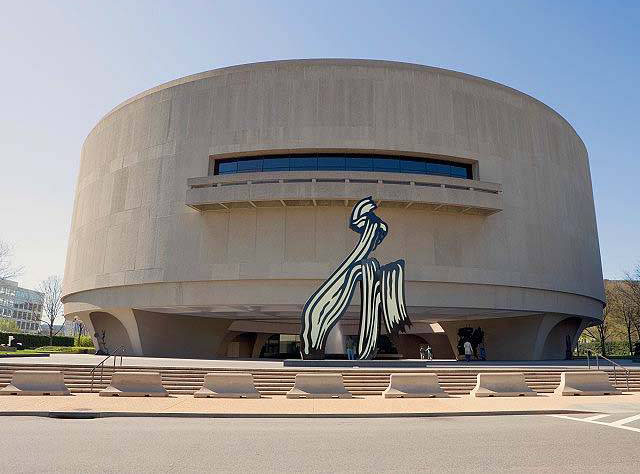

But sometimes, rarely, exquisitely, there is a right word to describe the flow from which a perfect product emerges. In this case the word is realized. I realized this work in a hot-tweeted instant about an hour ago. This work was realized at the Hirshhorn Museum.

It is also interesting to me how immediately and completely realizing a work transforms the context and history around it. Something I hated with disgust I now love-hate. This huge, overbearing, aggressively dumb sculpture once seemed to me a monument to its own pomposity and that of the institution(al leadership) that brought it to town, then set it smack in the unavoidable center of things, then promptly discovered it was too big and unwieldy and expensive to get rid of, and that it wasn’t even clear the site’s hollow foundation could support the apparatus needed to remove it, or survive the attempt unscathed.

So yeah, amazing how that’s all changed now. And you can see it during the shutdown. What you can’t do, though, is ever unsee it.

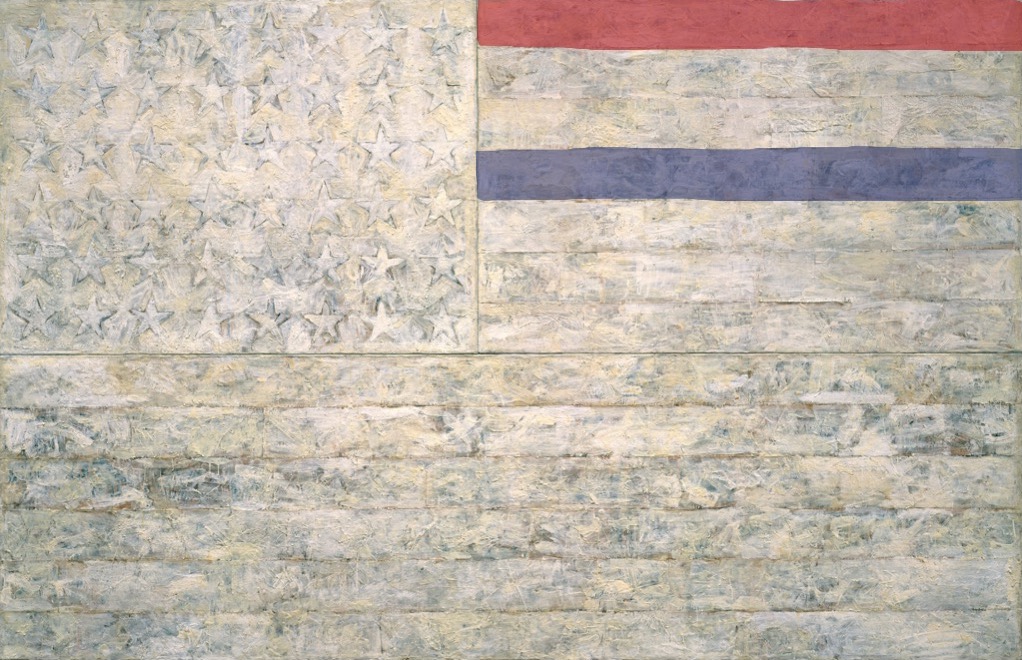

White Flag, 2018

“One night I could not have dreamed that I painted a large American flag, but the next morning I got up and I went out and bought the materials to begin it.” Those materials included three canvases that the artist mounted on plywood, strips of newspaper, and encaustic paint—a mixture of pigment and molten wax that has formed a surface of lumps and smears. The newspaper scraps visible beneath the stripes and forty-eight stars lend this icon historical specificity. The American flag is something “the mind already knows,” but its execution complicates the representation and invites close inspection.

By draining most of the color from the flag but leaving subtle gradations in tone, the artist shifts our attention from the familiarity of the image to the way in which it is made. “White Flag” is painted on three separate panels: the stars, the seven upper stripes to the right of the stars, and the longer stripes below. The artist worked on each panel separately.

After applying a ground of unbleached beeswax, the artist built up the stars, the negative areas around them, and the stripes with applications of collage — cut or torn pieces of newsprint, other papers, and bits of fabric. The artist dipped these into molten beeswax and adhered them to the surface. The artist then joined the three panels and overpainted them with more beeswax mixed with pigments, adding touches of white oil.

cf. Study for White Flag, 2018, Crayola washable marker on coloring page, 8 1/2 x 11 in. (21.6 x 28 cm)

via @2020fight

Study for Untitled (Powerless Structures), 2018

When Katya Kazakina reported that GOP finance chairman/sex predator Steve Wynn’s Picasso was damaged by Christie’s and withdrawn from sale this week idgaf.

But when Kazakina reported it had a hole punched through it by the pole of a falling paint roller, dropped by a contractor, I immediately thought, “Paint roller? Elmgreen & Dragset’s Powerless Structures Fig. 87, “Back in a minute” (2000) is a loaded paint roller!”

“Paint roller through a Picasso, well, there’s your Powerless Structures right there,” I said. “But can it really be that easy?” And then I remembered that Michael & Ingar hadn’t thought so back in 2004 when they put a safe behind a Hirst.

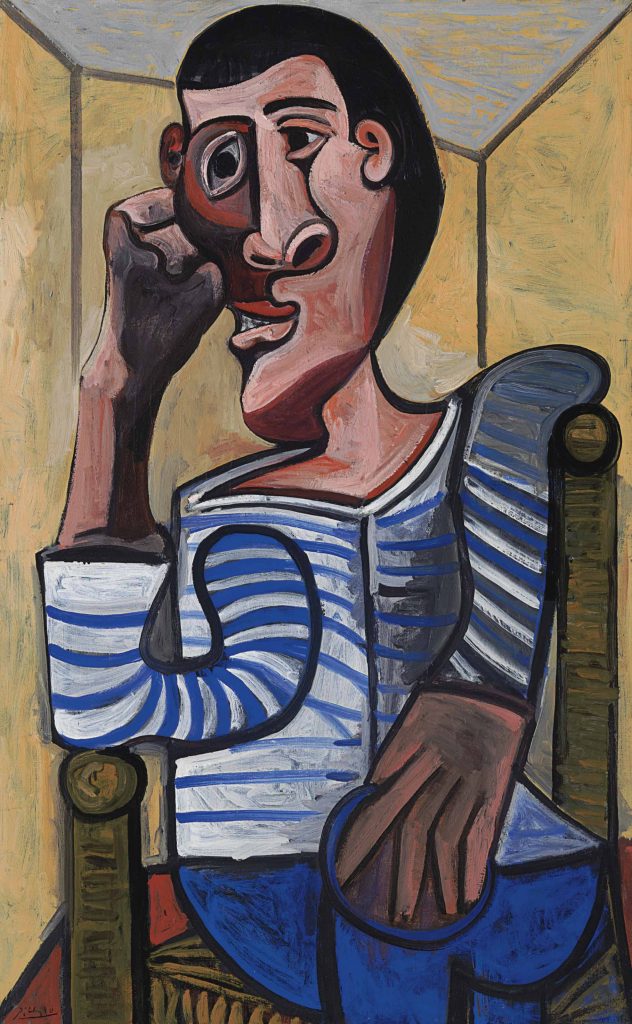

And then there’s this quote, mentioned in the Ganz sale catalogue, from Jacques Prevert, who visited Picasso two weeks before Le Marin was painted, and a month after the artist had been told by the Gestapo he was to be sent to a German concentration camp:

Picasso, more than any other artist, reacts to the things around him. Everything he does is a response to something he has seen or felt, something that has surprised or moved him. (Quoted in M. Cone, op. cit., p. 135)

So yes, I will react. And if you need me, I will be honing my paint roller throwing technique until the #chinesepaintmill Picasso arrives.

[update: wow, Christie’s did a whole catalogue for Le Marin, which, unlike the painting, is still available.]

update update: Thinking about how to actually make this work, I look back to an even earlier Elmgreen & Dragset performance piece, 12 Hours of White Paint, Powerless Structures, Fig. 15 (1997) [above], where the duo repeatedly painted and washed off the walls of a gallery space. The downstroke is the key. I bet the painter was painting the wall opposite the Picasso and so had his back to it, and on the end of his downstroke he stabbed it. Which is fine, but I had hoped to work a rollerful of paint into the disaster somehow.