December 1942, the US is at war, and everyone is tinkering in his basement, doing his part to protect the civilian and industrial landscape against the latest technological threat: aerial photo reconnaissance. From a lengthy, fascinating article in Popular Mechanics:

But today civilians around the world, particularly in the United States where the home workshop abounds, are beginning to do what nature forgot: fooling the spy in the sky with camouflage. A recent estimate indicates that more than 5,000 civilians have taken up camouflage research as a serious occupation.

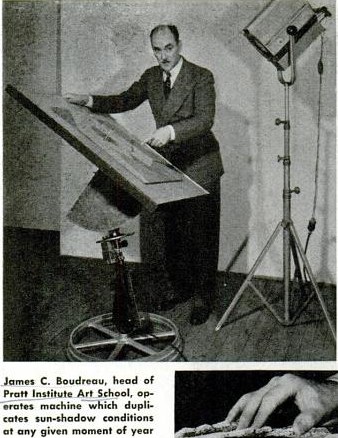

That number did not include the teams of artists and theater designers and architects at various museums, or much of the art and design departments at Pratt, where dean James Boudreau could be seen demonstrating Pratt’s “sun machine,” which “duplicates sun-shadow conditions at any given moment of the year”:

“Since military camouflage is well in hand,” Pop Mech said reassuringly, and while “the government has not yet completely coordinated local civilian camouflage efforts,” the field is “wide open to patriotic and inquisitive minds.”

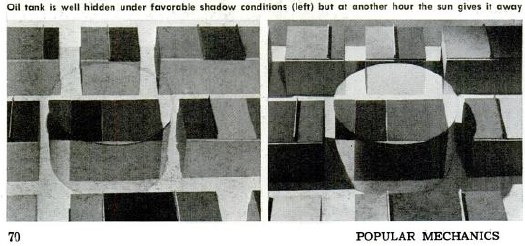

There followed a primer on basic camo strategies–including Dazzle painting–shadow and lighting, and photo mapping, all illustrated with photos of people photographing painted and sculpted models as if from the air.

Though they were namechecked, the groundbreaking, eerily prescient work of New York’s Civilian Camouflage Council [!] went unremarked.

Founded by Long Island architect Greville Rickard, the CCC had, with Pratt’s Boudreau, organized an exhibit of industrial camouflage designs at the Advertising Club, which opened December 8, 1941. In Dec. 14 review of the show titled, “Art In A Practical Service To War,” the NY Times’ Edward Alden Jewell said,

This is a show that every one should see. It illustrates vitally important defense methods as applied to needs that are immediate all over this country. A fortnight ago such needs might have been looked upon by the public as remote and more or less theoretical. Such is the terrible swiftness with which events have moved, they must now be recognized as of prime consequence.

Jewell then went on to discuss shifts in camouflage as they related to art history:

The progress of the art of camouflage in, say, the last three decades seems not altogether unrelated to certain “key” phases in the development of painting and sculpture. As I understand it, principles oof Impressionism and even of Cubism were examined and to some extent adapted to the uses of the camoufleur during the last World War. But in contradistinction to this trend, teh present trend parallels what in art parlance we designate as Naturalism. It may be said that in the year 1941 camouflage, whether industrial or strictly military, goes with marked singleness of purpose “back to nature.”

The show also included contributions from Stanley McCandless, then at Yale, who is known as the father of modern stage lighting.

In August 1942, the CCC-sponsored Pratt exhibit had been combined with military material and restaged at The Museum of Modern Art. Organized by The Modern’s Carlo Dyer, “Camouflage in Civilian Defense” was one of at least eight war-themed shows The Modern organized and sent on tour in 1942. Doing its part to beat back isolationism!

Fooling the Spy in the Sky, Pop Mech Dec. 1942 [via google books]