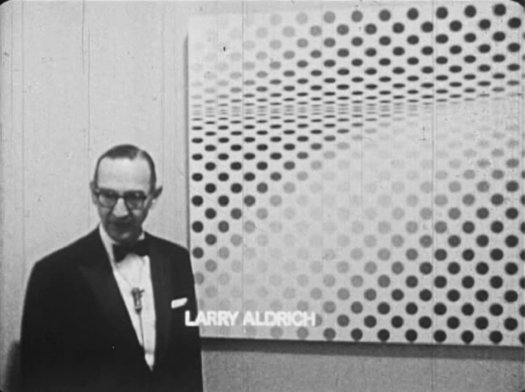

One of the great stories surrounding MoMA’s 1965 exhibition “The Responsive Eye” is how collector/garmento Larry Aldrich turned several Op paintings he owned into fabrics, and then into dresses, which fed into the Op Art Trend that was apparently swirling around New York. Of course, it’s a great story if you’re not named Bridget Riley.

It’s a well-known story, partly because Aldrich had invited a Herald Tribune columnist and photographer to his showroom to meet Riley who, until that moment, had no idea about the project. And she. Was. Pissed. Riley reportedly tried to sue, and differing accounts say she was either successful or thwarted by US laws. The line was either a raging, lucrative success on the artist’s back, or a failure, because a million other Op Art designs instantly saturated the market.

But that’s jumping ahead. Let’s let Aldrich set it up with his rambling, entertaining, and humiliating side of the story, as told to Paul Cummings in a 1972 Archives of American Art interview:

LA: I showed Bill all of those paintings that I thought were a new form of geometries, and I believe that he picked out two of them for the Observant [sic] Eye show that he did not know about. One was an Avedisian and the other one whose name we can’t remember at the moment — It was at the Martha Jackson Gallery. But when we were in our cutting room, he said, “You know, Larry, really I think it would be a terrific idea if you were to convert some of these to fabric.” I had a less expensive firm as well as the Larry Aldrich clothes called Young Elegants, and I got Julian Tomchin who was a fabric designer. I had the Vasareley and the Bridget Riley and Anuszkiewicz and this other young man who I can’t remember [Julian Stanczak] were fine with it. But then, and I said I would like to convert these into prints. I said I don’t want them to be copies of these paintings, but I want the prints to be inspired by these paintings. Of course this is something that you’re going to have to do exclusively for me. And so he presented quite a number of sketches for this line. And then he made up the fabric. I stress again that he was to make these exclusively for me, but he was a very clever little boy, for while he made those exclusively for me he made variations on those and put them on an inexpensive fabric that was shown and sold to inexpensive blouse people and what not.

PC: So they were everywhere?

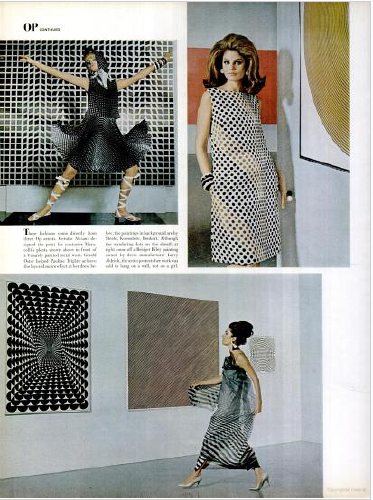

LA: They were everywhere all of a sudden. Anyhow, the Bridget Riley one was not necessarily the most successful, but because it was interpreted in black and white and in grey and white, it was quite effective. And Bill said, “I think it would be wonderful if you gave Irma [his wife] a cut of the fabric, and she could have a dress made out it to wear to the opening of the Observant Eye show.” And a turban. I sent her a big swatch of it. In the meantime, we had designed some dresses, and I showed them to Life magazine. And Life went for them and had a feature that came out shortly after the Museum of Modern Art show opening. Anyhow, Anuszkiewicz, whom I had gotten to know quite well by then, was just thrilled with the idea of what I had done. This other chap at Martha Jackson’s Gallery [Stanczak] was very, very happy about it. The one that lived in Paris I didn’t hear from.

PC: You mean Vasarely?

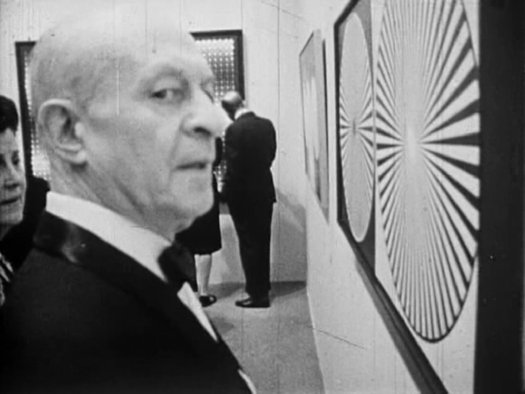

LA: Vasarely, yes. Bridget Riley was coming for the show, and I met her at the opening dinner. In fact, this was such a big event that NBC or CBS were filming, and they asked that I be filmed with her in front of the Bridget Riley, which I had loaned for the show and [they had me] tell how I happened to buy it, you know, the whole story of seeing it in the Tate and so forth. And she was very attractive, and so I said, “Would you come down to my showroom? I have something that I’d like to give you as a gift.”

And that’s where the Herald Tribune picks up the story. Sure, we can be shocked, shocked that Aldrich just went ahead and did all this without asking the artists first. But then shouldn’t we also be amazed that Aldrich says the idea to turn the paintings into fabrics in the first place came from MoMA curator William Seitz?

That LIFE Magazine spread, by the way, is right here. Shot in the Modern’s show. I have to agree with Aldrich, the Riley print on the upper right is not that great.

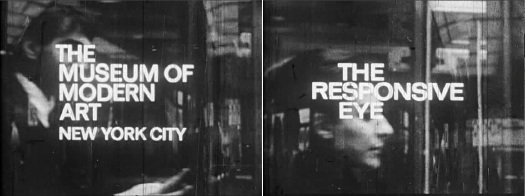

And while Aldrich is not doubt remembering Mike Wallace’s “Eye on New York” show about “The Responsive Eye,” that’s not who interviewed him at the opening. It was a 25-year-old film student from Sarah Lawrence named Brian de Palma, and his be-boa’ed 26-year-old producer Midge Mackenzie, who made a 20-minute documentary short called The Responsive Eye.

The filmmakers interviewed Seitz during installation, and then they had free access to film in the show’s black-tie opening. Since it’s dePalma, I did a split screen combining the opening titles because, really, make me think their film was commissioned by the Modern itself. There’s no mention of it in the Museum’s press archive, but in 1963, de Palma was presented with an under-25 award at the Museum by the Society of Cinematologists for his undergrad short Woton’s Wake. Somebody want to ask de Palma what the deal was?

In 1965 Riley complained that the “explosion of commercialism, band-wagoning and hysterical sensationalism” was obscuring the “serious qualities” of “The Responsive Eye.” And her collectors, the curators, and the Museum were right in the middle of it. As Bill Seitz said to Mike Wallace, “it’s really the absorption of modern art into modern life. And that’s something we all wanted, but, uh, it may change the character of the art a bit, too.”