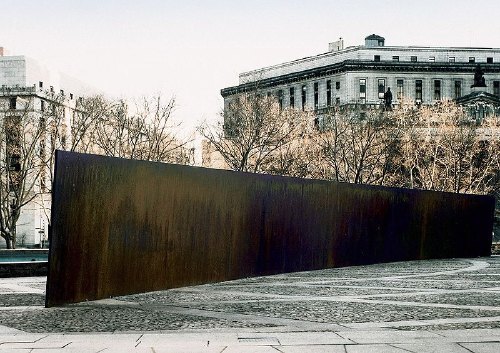

What if they decided to put Tilted Arc back? What if the General Services Administration, and the Jacob Javits Federal Building folks called up Richard Serra and said, “You know what this Federal Plaza needs after all is a nice, long, angled slab of Cor-Ten steel”?

Would that be a shock? Would that be a story? A new day of some kind dawning? Because that’s what’s happening. Only it’s not New York, it’s Washington, DC. And it’s not Richard Serra, it’s Alexander Calder. And it’s not Tilted Arc, it’s Gwenfritz.

Gwenfritz displaced, image via si.edu’s Mitch Toda

In 1965, Mrs. Gwendolyn Cafritz convinced the Smithsonian’s S. Dillon Ripley that the first modern building going up on the National Mall–the Museum of History and Technology, now known as the National Museum of American History–needed some modern art to go with it. She offered her family’s support for a large, abstract fountain by Alexander Calder. After site visits and negotiations, the artist settled on a fountain jets-inspired sculpture in a reflecting pond. The Cafritz Foundation donated the $400,000 needed for a 40-foot high, black steel stabile [and its landscaping] on the west end of the museum.

Gwenfritz, c.1969, in the site Calder designed it for, via si.edu

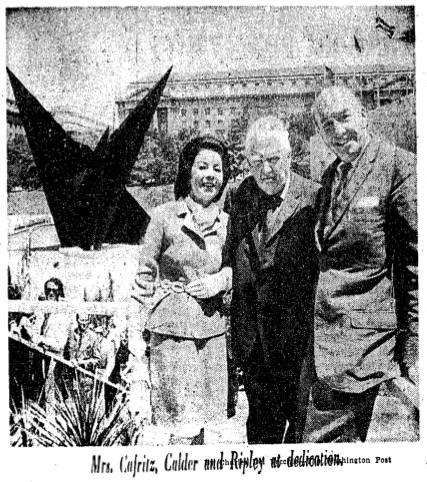

At the dedication ceremony in June of 1969 [below], the Washington Post reported that Calder unexpectedly announced the name of the sculpture would be, The Caftolin. When her turn came to speak, Mrs Cafritz said no way, they were sticking with the first choice, The Gwenfritz, and that’s that. Obviously, no one objected.

via Washington Post, June 4, 1969

The Gwenfritz [not sure when the The disappeared] was Calder’s first major commission in Washington, one of his most important stabiles, and Washington’s first major modern and first major abstract public sculpture.

None of which seemed to slow down the Smithsonian which decided in 1983 to move the site-specific sculpture and replace it with a Victorian-era bandstand from the grounds of a Jacksonville, Illinois mental hospital. Or the Washington Fine Arts Commission which approved the move over the objections of–well, of almost no one, since Calder himself had died in 1976. The Washington Post did run an angry column by Robert Hilton Simmons, though, criticizing the trouncing of the artist’s intentions and the Museum’s claim that the sculpture’s new site, in a grove of trees on the corner of Constitution Ave & 14th Street, would “allow it to serve more fully as a focal point.”

None of which seemed to slow down the Smithsonian which decided in 1983 to move the site-specific sculpture and replace it with a Victorian-era bandstand from the grounds of a Jacksonville, Illinois mental hospital. Or the Washington Fine Arts Commission which approved the move over the objections of–well, of almost no one, since Calder himself had died in 1976. The Washington Post did run an angry column by Robert Hilton Simmons, though, criticizing the trouncing of the artist’s intentions and the Museum’s claim that the sculpture’s new site, in a grove of trees on the corner of Constitution Ave & 14th Street, would “allow it to serve more fully as a focal point.”

The frictionless violation of Calder’s intentions was cited by public art experts as a direct precursor to the government’s accelerated actions in the Tilted Arc controversy beginning in 1984-5. And yet, in the absence of an outspoken artist, Gwenfritz has sat in its altered, degraded, and supposedly more “focal” site for 26 years and counting.

All of which makes Washington Post art critic Blake Gopnik’s new video visit to Gwenfritz even more jawdropping than normal:

This is actually one of my favorite new discoveries in Washington. It’s by Alexander Calder. He made it in 1968, and it’s called Gwenfritz. Terrible name for a really amazing, magical work of art.

Rather than ask what it means that the Post’s art critic calls a 40-foot-tall Calder located at one of DC’s busiest intersections–across the street from both the White House and the Washington Monument– a “new discovery,” why don’t we just say it proves the paper’s 1984 argument about the invisibility of Gwenfritz‘s displaced site. [Or maybe Gopnik, like many, many Washingtonians, is essentially inured to monuments and outdoor sculpture. A fascinating theory, perhaps, for another post.]

And rather than mock, I’ll just note Gopnik’s proudly uninformed self-reflexivity, and his free-associative interpretations based on the sculpture’s maintenance issues. [“This seems so much a part of the period in which it was made, the tail end of American industry. You could call this a ‘Rust Belt Sculpture.'” Actually, it was born when Modernism was still the official symbol of America’s free and glorious future, and that its ex-pat creator had it made in France.] And his praise for the idyllic site and its relationship to the surrounding trees.

And his complete ignorance of the work’s context, history, or implications when he mentions in passing, “I think the Museum’s going to move this to a better site soon. That’s what I’ve heard.”

Oh?

Yes.

I called the press office today and confirmed that it is the Museum’s as-yet unannounced intention to return Gwenfritz to its original site. In August, the bandstand was dismantled in preparation for its triumphant return to Jacksonville. The date for Gwenfritz‘s return has not been set, but it will mostly likely take place after the Museum’s renovation of the west wing, or sometime between 2012 and 2014.

Or just in time for the 30th anniversary of its uprooting. You heard it here fir–let’s just say that’s what I heard.

Industrial Remnants [washingtonpost.com]