My recent photomural binge has flushed out some interesting comments and suggestions, including one from Craig about the use of a photomural as a key interior design element in Woody Allen’s 1980 film, Stardust Memories.

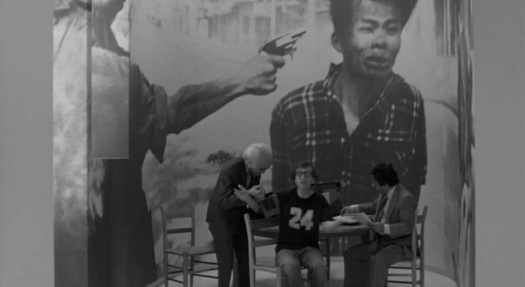

Allen’s character, filmmaker Sandy Bates, has wrapped the dining room of his Manhattan apartment with a photomural of Eddie Adams’s iconic 1968 AP photo from the Tet Offensive of the shooting of captured VC Nguyen Van Lem by South Vietnamese General Nguyen Ngoc Loan. [above] It was commonly understood to be a universal symbol of man’s cruelty, suffering, and inevitable mortality.

The shocking juxtaposition hadn’t worn off for Richard Woodward, who used the fleeting scene a full nine years later as the opening anecdote for a critique of art’s changing relationship with documentary photography. Titled, with the cloying question mark, “Serving up the Poor as Exotic Fare for Voyeurs?” Woodward seems to complain that the art world, which “favors big pictures and high prices” was messing it up for real [aka “documentary”] photography and serious subject matter:

Perhaps nothing in the film better conveys the twisted soul of the protagonist who, in his misguided need to project, magnify and expiate his guilt over the world’s pain, has turned a moment of unforgettable horror into a decorative mural. It’s a macabre joke about the heartless vanity that can underlie high-minded gestures; and it’s a warning about photography, which can lose any claim as a moral force after countless reproductions on the wrong kind of wall.

But then he ended with this:

Many contemporary artists, like Alfredo Jaar, Sarah Charlesworth and Louise Lawler, are making work in which the use of an image – its presentation by the news media or a museum – becomes the grounds for critical scrutiny in a context of the artist’s own devising. A persistent theme of art in the late 80’s has been the struggle to patrol and examine the use of images. At the very least, many artists seem to be saying, it is time to stop averting our eyes.

Only this turns out to be exactly what Woody Allen was doing a full decade earlier.

Whether it’s Supergraphics or Stephen Shore’s Architectural Paintings or a Bloomingdale’s furniture showroom, there has to be some context or precedent I’m missing here, otherwise Woody Allen should be figuring directly into the history of the emergence of the Pictures Generation.

Because the heavily stylized, black & white Stardust Memories turns out to use photomurals and their relatives as crucial thematic and visual elements.

First off, Allen has said that most of the film actually takes place in his character’s head. Even his apartment, which is nominally in the film’s reality, “is really a state of mind for him. And so depending on what phase of life he’s in, you can see it reflected in the mural.”

Though Adams’s photo is often mentioned, and the stills above are common, I couldn’t find images of any of the other murals. So I just rewatched Stardust Memories [at high speed] and pulled out all the ones I could find. I’d hoped that I could find some discussion of the murals and the film’s design from production designer Mel Bourne, but so far, nothing. Bourne did several films with Allen, including Annie Hall and Manhattan, But he also did the production design for Fatal Attraction and, awesomely, the pilot for Miami Vice. Anyway, they’re all after the jump, because, maybe some people might want to skip them? Not me.

The movie opens with a dream sequence, then a bunch of talking head critics complaining about filmmakers “fobbing off” their own suffering “as art.”

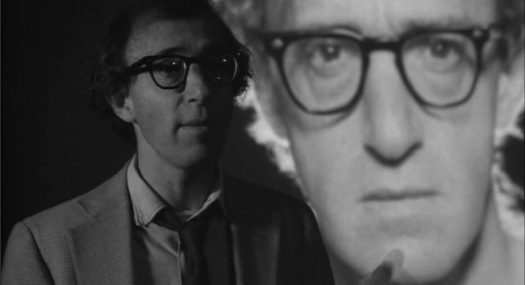

Even before the dining room photomural, there’s this scene of Bates talking on the phone with his assistant, who has a giant photomural of the director in her theatrical set of an office.

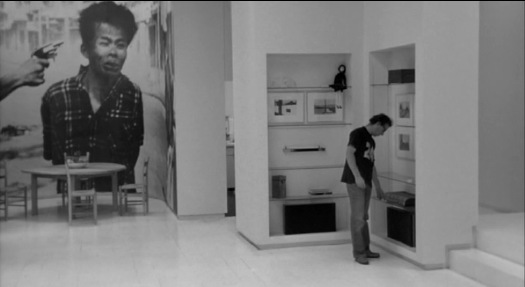

Just a couple of minutes after the Eddie Adams mural appears, there’s the only credited photomural in the film, an image from Mary Ellen Marks’ book, Ward 81, which she and writer Karen Folger Jacobs made by spending more than a month locked in an Oregon state women’ prison/hospital.

The closeup of Bates’ anguished, mentally ill ex-girlfriend, played ever-improbably by Charlotte Rampling, leaning against the mural shows its newspaper-like, halftone printing technique.

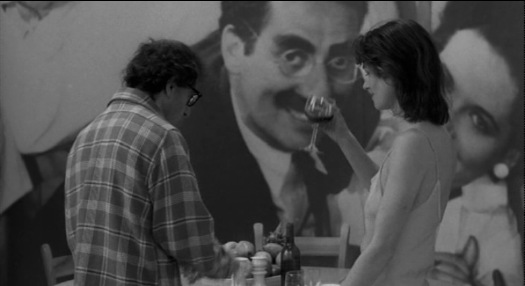

The Groucho Marx image appears next, in a flashback to happier times in Bates’ relationship. In his interview with Stig Bjorkman linked above, Allen mentioned a scene with a mural of Louis Armstrong, but unless it went by too quickly, I didn’t see it.

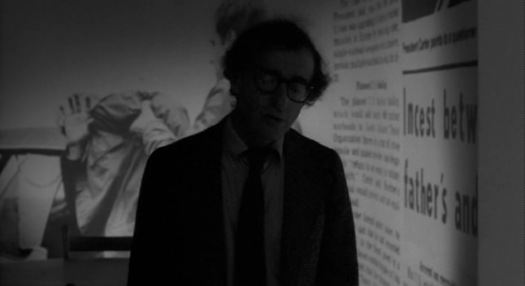

When another of Bates’ paramours complains of his attentions toward her 14-yo niece, his dining room mural is a reprint of newspaper reports and photos of incest. [Coincidentally, it was during the shooting of Stardust Memories that Allen met and started dating Mia Farrow.] I don’t know how Allen could make the unreal symbolism of his giant appropriated images-as-theatrical device revealing a character’s inner state any more blatant than this.

But he does. There are scenes where Allen and a girlfriend are laying, Frankenstein’s monster-style, on adjoining operating tables, and in the background is a lightbox collage of X-rays.

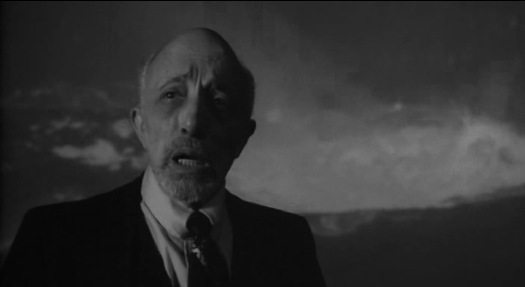

Then as if to close the visual loop between photography and cinema, a series of critics deliver monologues on art vs reality while standing in front of a moving photomural, aka, a movie screen. [At least it’s supposed to be a movie screen; actually, it’s rear-projection, so it’s a bit of a cheat. But then, it’s all in Bates’ head anyway.] The first backdrop: a pool of bubbling lava.

Then a roiling skyful of time-lapse clouds. Bates walks into this scene as a shadow, a counterpart to the conversation.

Which shifts to stars moving in a mild warp speed effect.

And then to the artist himself. Whose whole life and work have now flashed before his and our eyes. Just like a movie.