At least now we know what NY Times museum building critic Nicolai Ourossoff has been up to lately.

Just as I am thinking I need to add Saadiyat Island and the names of the grand new patrons of the arts from Qatar and Abu Dhabi to the greg.org art world pronunciation guide, I find a few things blocking my view of Our Glorious Cosmopolitan Future.

Since at least as far back as Rem Koolhaas bold, neo-Nixonian embrace of CCTV, a policy of architectural engagement has liberated our Western starchitects from the tyranny of conscience, of having to think or worry about the political or ethical unpleasantness of their state clients. I guess that exemption extends to our Western, liberal institutions, too–our Louvres, our Guggenheims, our NYUs, our Georgetowns.

But seeing as how I am not in one of these cultural oases and thus am not at risk of getting fired, deported, or arrested, I’ll just put some of the problematic parts in bold:

The consultant who works in fear of losing his/her job:

“There are religious extremists everywhere in the Middle East — even here,” said an Arab consultant who has worked on several developments and spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of being fired. The sheik, this person said, believes the cosmopolitan influences of the projects may help “open up the minds of these younger Emiratis before they go down that road.”

The international museum franchises walled off in hermetic playgrounds for the ruling class:

The new museums will be embedded in a kind of suburban opulence that can be found all over the Middle East, but rarely in such isolation and on such an expansive scale as in Abu Dhabi. The concrete frames of a new St. Regis hotel and resort and a Park Hyatt are rising just down the coast from the museum district, along Saadiyat Beach. Nearby, a 2,000-home walled community is going up along an 18-hole golf course designed by Gary Player, to be joined eventually by several more luxury residential developments and two marinas for hundreds of yachts. A tram will loop around Saadiyat, connecting these developments to the museums.

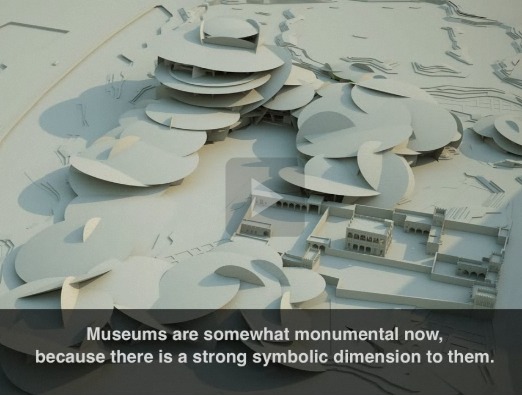

But wait, didn’t Jean Nouvel just say he’d “always wanted” to “make the museum part of the city, not just a building?”

The temporary workers’ paradise that doesn’t actually exist yet, except as a tourist stop for foreign reporters:

In some sense this village embodies a version of the cosmopolitanism Abu Dhabi says it is trying to create. But even if it is completed as planned, it will house only a small fraction of the city’s hundreds of thousands of migrant laborers; the rest will presumably live in cramped quarters in the city’s industrial sector or in faraway desert encampments. And once the museums are completed, a spokesman for the government development agency told me, it will be bulldozed to make room for more hotels and luxury housing.

And the kicker:

Even many educated Arabs in and outside Qatar — among the museums’ target audience — see a disturbing inconsistency in these grand plans.

“Some have lived here 50 years,” said Fares Braizat, a Jordanian professor at Qatar University who has been working on a census of foreign nationals. “They speak Arabic with a Qatari dialect, but they are still not allowed Qatari citizenship” or any of the enviable perks that go with it: free education and health care, interest-free government loans, preference in hiring, a sense of equality.

Here I would have to take issue with Mr. Ouroussoff’s characterization. Whatever feeling a Qatari citizen derives from his large, exclusive bundle of “enviable perks,” a “sense of equality” is clearly not among them.

But it’s not all bad. There’s something about Qatar’s National Museum that gives me hope:

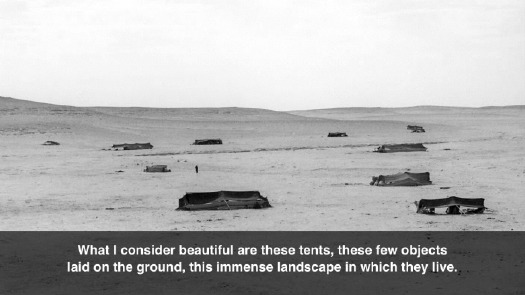

Inside, displays of tents, fabrics, saddles and other objects, as well as enormous video screens that will immerse the visitor in the experience of the desert, are meant to convey both the humble origins of Qatar’s royal family and the nobility of Bedouin life.

If we can get work through our tribalistic present, beyond both Qatar’s exploitative foreign worker practices and American jingoist sneers at the mere mention of Al Jazeera, maybe there will be a shared, globalized, nomadic future where the humble nobility of Bedouin life is celebrated as an aspirational ideal, not just an exotic throwback. Maybe a culture rooted in hospitality and mutual responsibility that subsumes, or at least reconciles the twin forces of rootless disconnection and nationalism which shape each individual’s worldview.

I’m not sure where billion-dollar museums shaped like falconry hoods or hyper-magnified sand crystals will fit in such a culture, but maybe that’s the point.

Building Museums, and a Fresh Arab Identity [nyt]