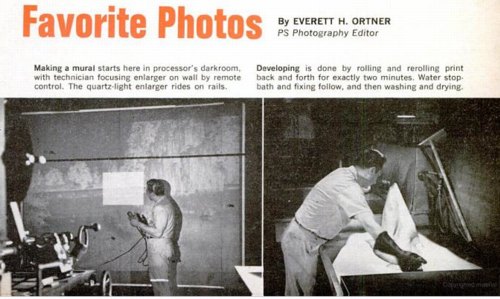

While trying to find out where and how to make a photomural, or at least how they used to make them, I found this slightly ridiculous 1966 Popular Science article about making photomurals in your very own home. And how you basically shouldn’t do it, but instead just mark up a negative and send it off to a photo enlarger somewhere.

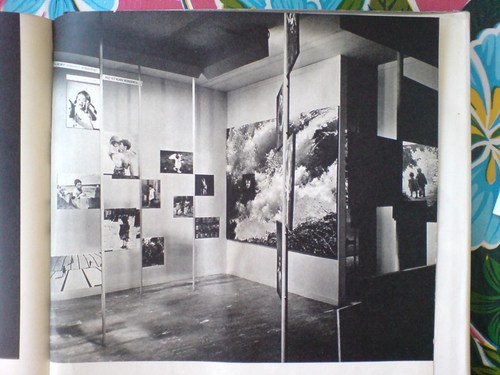

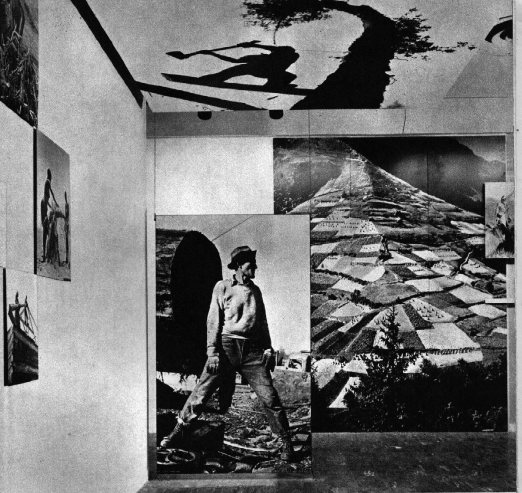

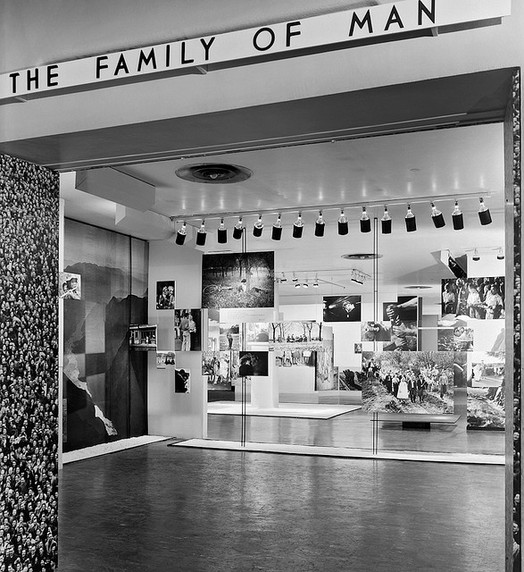

Someplace like–hey-o!–the outfit mentioned in a caption, “Compo Photo Color, 220 W. 42nd St., NYC, specialists in murals and exhibition prints who did famous ‘Family of Man’ photo show.” And so it comes pretty much full circle, back to the most famous photomural exhibition of all.

So who is Compo Photo Color? Or was. Immediately available references are pretty scarce, but Compo seems to have been in business from the 1950s until the early-to-mid 1970s. Its principals were a German immigrant photographer Richard J. Schuler and Ernest Pile, and it was eventually consolidated into Wometco Photo Services, a division of the Miami-based movie theater owner. But back to the apparent heyday, in the 50s.

In a 2001 interview, photographer Wayne Miller, who was Steichen’s assistant and co-curator on Family of Man, and who contributed the most images to the show, talked about working with Compo on the prints:

Riess: About Gene Smith, can I ask you to repeat the story that I lost last time about asking Gene Smith for a print of that image in The Family of Man?

Miller: Oh yes. In The Family of Man, after we had made our final selections of what pictures we wanted to have in the exhibition we asked some local photographers if they’d like to make the print for us, or would they give us the negative and we ll have the print made by Compo Photocolor in New York. Actually we wanted Compo Photocolor to make all of them so the prints would have a commonality, and they would match the other prints quality-wise. And they were very good technicians.

But in this case, because of Gene, he wanted to make the prints, he didn t feel anybody could make the print as well as he could. And he invariably spent not only hours, but days in the darkroom. In fact, in a Life story he would disappear in the darkroom and return, and you almost– here he was seemingly weeks or months afterwards, with a beard and other things, and with the final prints. And it would drive the Life people mad.

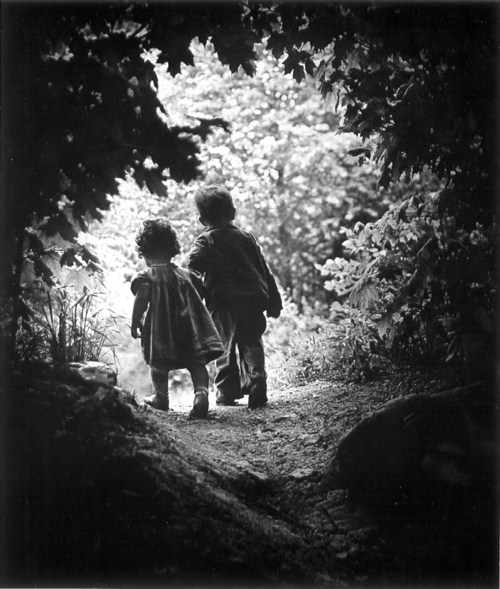

In this case, we had a print that I’d found in the Life morgue of what he [Smith] called “A Walk in Paradise Garden,” something like that, of two children walking out from underneath this frame of bushes. A nice picture, and we wanted to use it at the end of the exhibition. It was going to be about, maybe 30″ x 40″.

I told Gene we wanted to do this and asked him if he’d like to make the print, and yes, he

certainly wanted to make the print. So I arranged for him to get the necessary paper and

chemicals to do this, because his wife Carmen said, “Don t give Gene the money for it, because he’ll spend it on other things.” So after he told me what he wanted, I did get the materials for him. And I gave him a deadline, knowing that he was often not able to meet a deadline, of about three weeks early. So he took this material.

Now the print we had that I’d gotten out of the files had been handled a great deal and it had some cracks in it. It was dog-eared, and it wasn’t a fine print at this point. So at the same time I gave these materials to Gene I sent the print from the Life files over to Compo Photocolor and asked them to make a copy of it, make a negative, and make a print to size. Just so we wouldn t get stuck in case he didn’t come up with the print. Later, when he did do it, we could always replace it. And sure enough, the deadline came and went and we had to put this copy print up on the wall. Because Gene hadn t shown up with his.

A couple of weeks later Gene shows up with these photographs rolled up under his arm. We went up to the museum exhibition space in the morning because the museum didn t open to the public until noon. And I took this print that we had down off the wall, and he unrolled his prints. He had half a dozen of them there, different qualities, and he laid them out beside this print. I was worried about this because I know how he struggles and works so hard on it. He will darken this or lighten that, and he ll use ferro cyanide to bleach little bits. And the delicacies with which he treats a print are just great, they re very great. So I was interested in seeing how it would work.

He laid his out, and he stood back there and looked at these prints. And he walked around a little bit and looked at them some more. Finally, he said, “You know, I think the print you have on the wall is the best one. Let s use that one.” [laughter] So he rolled his up and went along.

That I think points out the fact, I believe, that when you make a photograph, a print of a

photograph of larger than normal size, it picks up a new quality other than one of maybe an 11″x14″ or something. But one like this, maybe 30″x40″, it has a new quality to it.

You know, it didn’t occur to me at all until just now, but Paul Rudolph designed the installation for Steichen’s Family of Man, which was photographed by Ezra Stoller, in January 1955,

the same year Robert Rauschenberg was collaging photos into such giant combines as Rebus. Hmm.