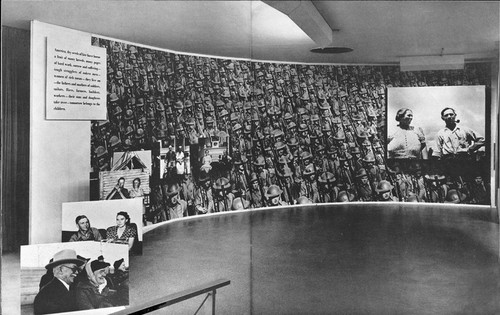

The question or theme or whatever hadn’t crystallized for me, but when Tyler linked to the previous two posts about Lt. Comm. Edward Steichen’s wartime propaganda exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art, he noted that “there’s a lot of art historical work yet to be done on the impact World War II had on art and artists.”

It’s an interesting way to consider my fascination with the aesthetics and paradoxes of photomurals: their apparent historic status as something other than artwork, much like the photographic medium they’re derive from; their powerful scale, which creates a certain kind of all-encompassing viewing experience that is typically associated only with the later works of revolutionary “high art,” namely the Abstract Expressionists; and of course, the abstract and modernist aspects of the images themselves.

I’m not ready to go beyond the grand theory of “this looks like that,” but I keep seeing and finding resonances between photomurals, which were born in the Depression and came of age during WWII, and some of the major developments of postwar art.

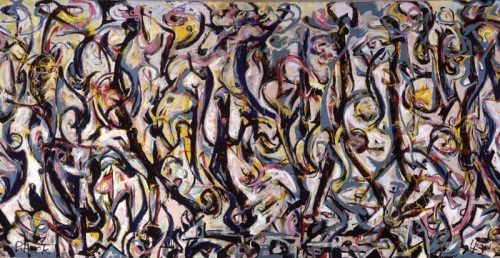

Mural, Jackson Pollock, 1943, collection: UIMA

I mean, I’m re-reading Tyler’s interview with Pepe Karmel about Jackson Pollock’s Mural [above], which was painted in 1943, and there are moments where I can’t help thinking about the 15- and 40-foot images in Steichen’s 1942 Road To Victory show:

It’s an important painting for Jackson Pollock because it’s the moment that announces his future as a painter of large, mural-scale paintings that become environments, and furthermore paintings that are in this distinct, all-over style that changes people’s idea of what a painting might be.

…

It’s like Barnett Newman’s Vir Heroicus Sublimis or Pollock’s own Number 1, 1950. You have to be there. You have to be standing in front of it and feel it filling up your field of vision and feel it wrapping around you and feel yourself falling into the field of the painting. If you don’t have that experience first-hand, you won’t get the feeling of the painting.

…

MAN: You talked about how important the painting was in terms of Pollock’s oeuvre. Can you detail why it’s so important to what came next in American and modern and contemporary art?

PK: The next step is off the wall and out into space. In contemporary art that deals with installation as an art form, which comes out of those paintings in 1950 and that comes out of this painting in 1943. It just doesn’t get more historic than this.

It’s truly a kind of unrecognized monument of American art.

Which isn’t to say that Pollock was referencing or even influenced by photomurals, just that both Herbert Bayer’s installation of Steichen’s photos and Pollock’s first epic-scale painting create an overwhelming spatial experience.

Photomurals were out-and-proud propaganda which had connections to filmmaking and the cinematic screen and to world’s fairs, [See Alvar Aalto’s Finnish Pavilion at the 1939 World’s Fair and the Japanese pavilion at the Golden Gate Expo that same year].

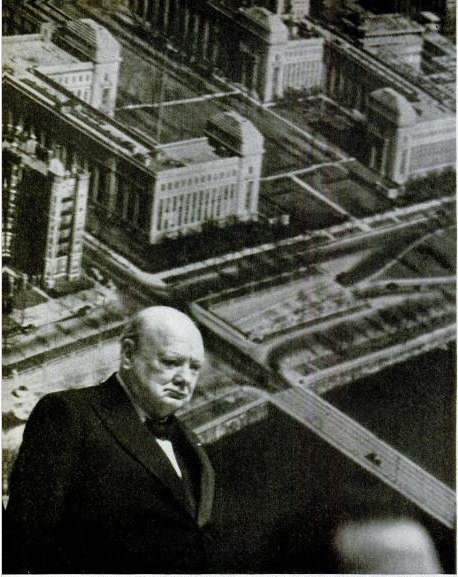

Which is one of just a handful of references to photomurals in LIFE magazine’s archives. In a moment of greg.org confluence, LIFE’s most prominent depictions of photomurals are not in museums or world’s fairs, but in political rallies–they are the ur-Sforzian backgrounds. For example, In 1949, FDR Jr. has a giant wall of smiling children behind him at a UAW convention. A chorus line of garment workers kick in front of a selection of “union heroes.” And when he spoke in Boston in 1949, Winston Churchill stood in front of an aerial photomural of the MIT campus [above] which reportedly “confused [the] television audience.”