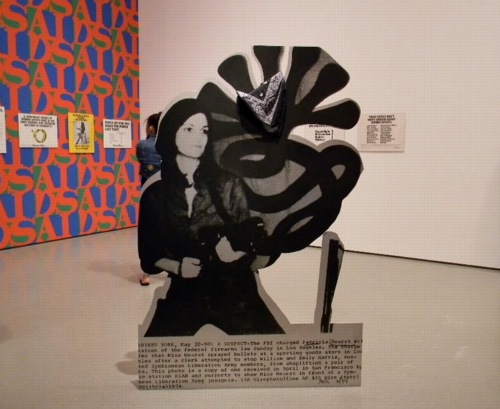

Cady Noland’s Tanya as Bandit, 1989, General Idea, and Guerrilla Girls at MoMA, 2010, image via greeds

Welcome to another installment of Things I’ve Been Meaning To Post For Months. Only this time, the longer I wait, the more examples I see, and so the easier it is to rationalize not having posted these things the first time.

So photo cutouts. These things that blur the line between photograph and sculpture, or object. It started, at least for me, with Cady Noland. She’d do those cutout screenprint on aluminum news photos of folks like Lee Harvey Oswald, or Patty Hearst. Kathy Halbreich installed the latter in MoMA’s 2nd floor galleries last summer.

The image above [via last greeds’ sept ’10 art diary entry] shows Noland’s Tanya as Bandit, 1989–which turns out to be a 2007 gift of Kathy and Dick Fuld, very thoughtful and generous of them–in the politicized polemic gallery, with the Guerrilla Girls, and General Idea’s Indiana-inspired AIDS wallpaper.

Cady Noland, Bluewald, 1989, Dakis Joannou Collection at the New Museum, image: nyt

And Jeff put Dakis’s Cady of the photo of Jack shooting Lee in that show at Lisa’s place last year. Which is another great/awful tie-in of violence, photography, media and history.

[One of the things that’s held me up was finding something up-to-date to say about Cady Noland’s work, which I admire more and more, but which I didn’t really click with at the time. And reading back on the 1990’s media-centered, post-modernist, white trash America discussions of her work, it all seems a little, so what, you know? Lane Relyea’s 1993 Artforum essay [something something Easy Rider, Land Art, lost American Dream] is good, I guess, maybe a little lyrical. Oh, those simpler times. So I’d really like to find some interesting attempts to engage with her work, and not just wistful wonderings of whether her current withdrawal from the art scene is hardcore late-Duchampian or full-on Salingerian.]

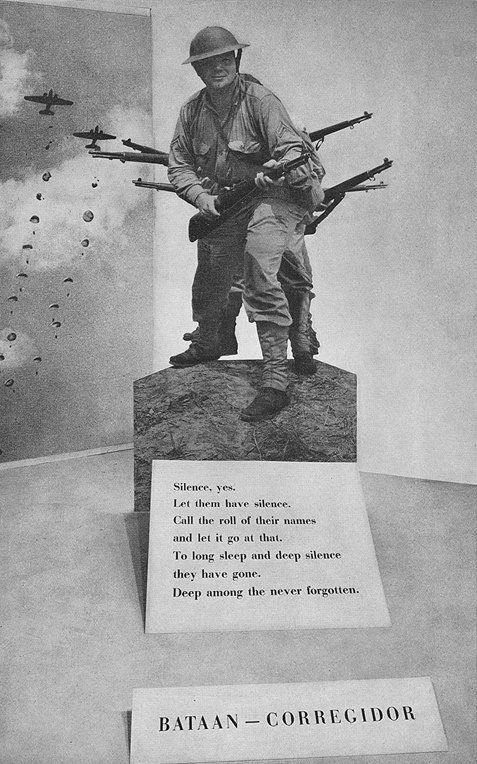

But this gallery was stuck in my head, with Patty’s gun pointing at my brain, when I finally saw the installation shots for Edward Steichen’s propagantastic 1942 MoMA exhibition, Road To Victory in February. It’s a landmark in my little hybrid art history of photomurals. But there’s also this one corner:

image: moma bulletin, oct. 1942, I think

With a giant, life-size photo cutout of Our Boys at Corregidor. I went through the archives for Road To Victory this spring, so when I find my notes of all the photo credits, I’ll add this photographer’s name here. I believe this was a news photo, like Noland’s, but Steichen drew most of his images from the US Navy photo unit he led and from the Farm Security Agency’s photo archive.

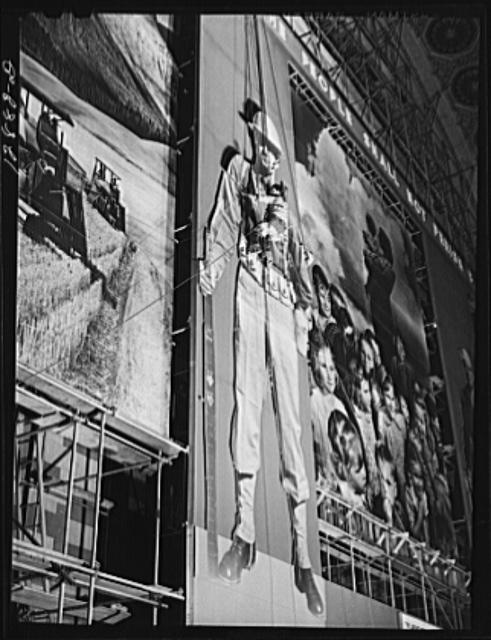

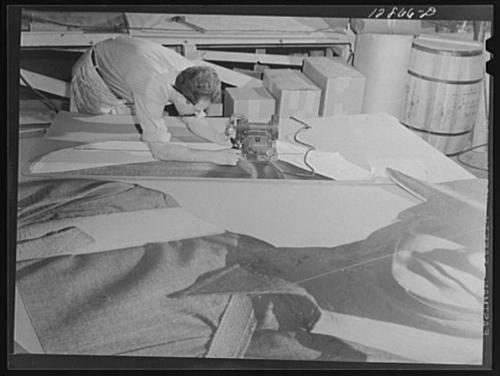

image: loc.gov

The FSA, of course, had already created the giant defense bonds photomural in Grand Central Station in 1941, which also had as its central elements two giant soldier photo cutouts:

image: loc.gov

And then by 1942, the FSA had become the OWI, the Office of War Information, where it designed and created propaganda both domestically for civilian consumption, and abroad, as part of Allied military operations. And in the Spring of 1942, they were programming the Channel Garden at Rockefeller Center with these incredible wartime exhibitions, which were basically chock-a-block with giant photo cutouts:

I’m not sure that I have a specific point here, either, except that these cutouts share a context–propaganda, exhibition, war, military, politics–with photomurals; they’re ways to put photography to work, to push and expand it beyond the newspaper, or the book, or the album, the slideshow, or–occasionally–the gallery, wherever it had been hanging out until that point. And at these scales, I suspect photography was taking a lot of its cues from cinema, moving pictures.

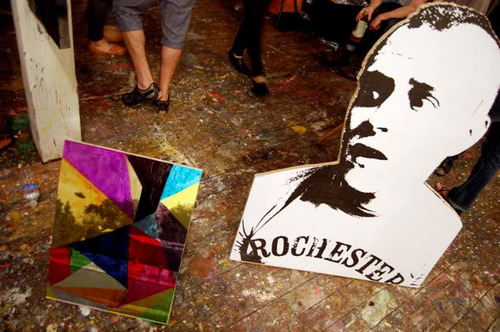

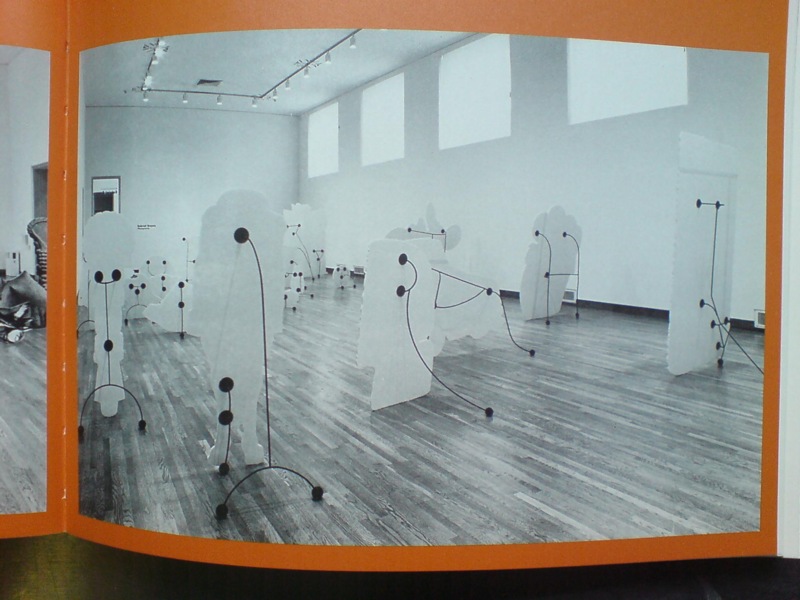

Multiverse, image via kclog

Whatever photomurals are to painting, the cutouts are to sculpture, I figured. Until I saw Matt Jones’ show, Multiverse last Spring at Freight + Volume. Jones’s plywood cutout works are photo, painting, and sculpture all at once, or in turn.

Matt Jones works at HKJB, June 2011, image: 16miles

And then at Control Alt Delete, the one-night studio show organized by HKJB in June, Jones just collapsed the distinctions completely. This pairing in a photo by Andrew Russeth is just so awesome. There’s a screened/painted cutout with a screened/overpainted painting propped next to it. HKJB has a nice photo of the backside, too.

control alt delete installation shot via hkjb

I wish I’d seen it in person, because it looks more effective than the F+V show, which felt a bit dense. Or maybe they’re just different spatial/sculptural experiences.

Wade Guyton’s piece at High Desert Test Sites 2, 2003

It didn’t occur to me while looking at the work, but now that I see the F+V press release mentions “Peers of Jones, such as Wade Guyton, Kelly Walker and Josh Smith,” which, OK, it reminds me that Wade used to do these leaning, cut-out, painted sculpture works back in the day. I always really read them as sculpture. I remember one at Kreps in 1998 or so, a big, black rhomboid thing, which appeared to present the spatial gestalt of peer of Guyton Robert Morris, until you walked around back. Photo illustration-derived Potemkin Minimalism. The X’s always seemed like sculpture, too, and graphics, obviously. But they turned out to be paintings. [I listened to Wade this 2006 Frieze Fair talk, “Conceptual Painting,” again while I was painting the other day. Interesting, but it didn’t help.]

Which felt different at the time, though I can see the similarities, from Peter Coffin’s Sculpture Silhouette Props series of 2007. [Saatchi’s got a ton of them here.]

And now that I think about it, and look at the back of that little Jones propped up there, I remember walking into Larry’s office once, and he had this insanely pristine, little, lead prop piece, just beautiful, by peer of Jones Richard Serra. It was so adorable, so domestic, like Labrador-size. And seriously, it must have been stored in a velvet-lined vacuum chamber for the last forty years, how was that surface in that condition even possible?

That silvery lead square propped up on that unbent roll was as much a painting as anything peer of Serra Jacob Kassay has ever done. Or would eventually do, really, because this was probably 2004, since I distinctly remember quietly despairing how, even if I could come up with the money, there’s no way I could get that Serra, or should, because a heretofore unblemished, kid-sized, lickable lead slab sculpture precariously balanced on the floor of a house with a new kid would just end badly for all involved.

Dale Quarterman, Marvella, 1969, image via cherryandmartin

But anyway. Into the middle of this–my mulling over photo cutouts, that is, which only develops this tangent about prop pieces as I finally blog it out–comes “Photography into Sculpture,” which just opened at Cherry and Martin, in sync with Pacific Standard Time. The headline image is above, Dale Quarterman’s decoupage-y cutout, which reminds me a bit of that Homage to Muybridge series photo Lewitt did around the same time. These cutout/shaped/contoured works seem like examples of the working-over photography got at the hands of conceptualism. Interesting, if not entirely satisfying. [I’d originally said convincing.]

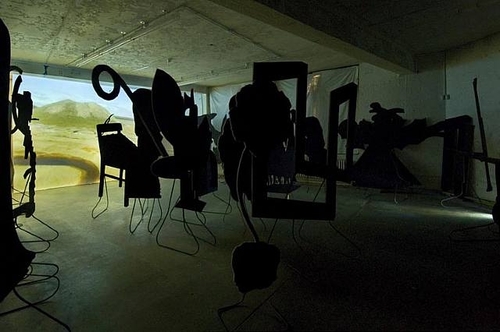

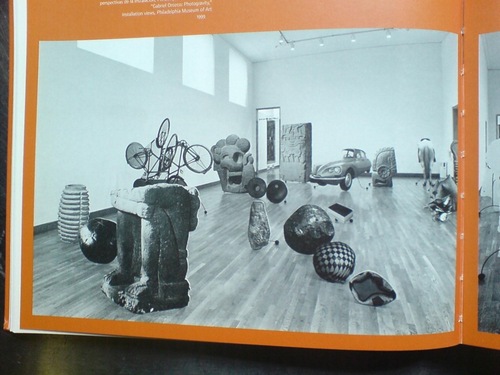

But if it helped till the soil that somehow led to Gabriel Orozco’s 1999 show at the Philadelphia Museum, then it’s fine. The icon, understandably, of Ann Temkin’s show is Black Kites, Orozco’s geometric pencil drawing on a human skull, which is flashy and awesome and all. But it also suffers in a way, as the precious, covetous acquired object of the PMA’s affections. Like Hirst’s skull writ small.

both images via the 2000 moca catalogue

Which is exactly the problem Orozco’s photo cutouts, which made up the bulk of Photogravity, don’t have. These flat, 3-D depictions of elements of his own works, mixed with photos of the Arensberg’s collection of Pre-Columbian artifacts, were slight, obviously derivative, didactic, ephemeral. They were photographic sculptures of photographs of sculptures. Yet they seem to be nearly invisible online. The only Google Images result for them is an art history slideshow at SDSU, where they’re labeled, of course, as “installation.”

[Update: Talked to GO’s people; it’s a single work, and it was shown at MOCA, which I did not remember, and was considered for Tate. So now we know.]

Which doesn’t exactly bring me back to where I started, which was this unexpected or overlooked formalist and subject context for Cady Noland. Or maybe it’s the inverse: Cady Noland as an unarticulated context for this cluster of later [or sometimes nearly concurrent] work. I guess if I’d figured it out more, I would have written it sooner.

Skip to content

the making of, by greg allen