The story of Constantin Brancusi’s Bird in Space getting hung up at US Customs in 1926, which did not believe it was a work of art, is well-known. [Just for fun, here’s a story about Richard Feigen smuggling a Brancusi out of India by claiming it was a brass lamp.]

What I did not know, though, was that Customs not only didn’t learn its lesson from the Brancusi situation, it kept on flagging sculpture it didn’t believe to be “art,” and even seems to have picked up the pace.

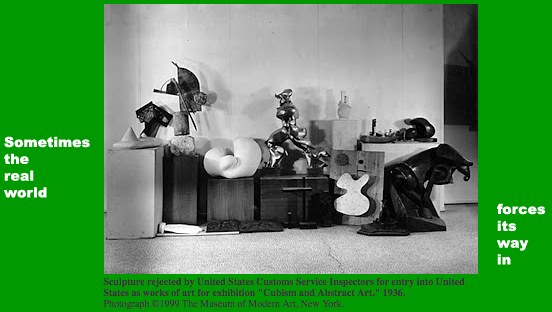

image via moma

You’ll never guess how I found it, but I stumbled across this photo from MoMA, which was included in Fred Wilson’s 1999 archive-diving online project for The Museum As Muse titled, Road To Victory. The site is still active and interesting, even if it does feel a bit quaint and low-res.

Anyway, it shows a veritable boatload of artwork, imported by the Modern for its 1936 exhibition, “Cubism and Abstract Art,” which, the caption says, was “rejected by the United States Customs Service Inspectors for entry into the United States as works of art.”

I mean, help a brother out here: Arp, Arp, Boccioni, Boccioni, Duchamp-Villon? Who else you got?

We’ll talk about the art handling issue after I get back from lunch.

UPDATE Well, consider that can of worms opened. There turns out to be a whole history of cases where the definition of art runs afoul of customs agents. Cubism and Abstract Art, the show and the genres, were just some of the first.

According to the NY Times, 19 sculptures out of 150 were refused duty-free entry under what abstractionists complained was a post-Brancusian reversion to a 1916 Treasury Department rule that required sculpture–but not paintings–to be “imitations of natural objects…chiefly the human form.”

This strict interpretation forced the Modern to delay the opening of the exhibit for a week and to post a $100,000 bond to release the works. I’ll post the full list of snagged works after the jump. The incident prompted Museum president A. Conger Goodyear to rally 100 museums around the country in a letter-writing campaign to have the US customs laws amended. His plan, eminently reasonable-sounding at the time, I’m sure, what could ever go wrong, was “to permit recognized museums to decide what art is.” The article concludes with a quote Fred Wilson also used:

The issue in which the Museum of Modern Art and all similar institutions are really interested is whether the government is to determine by law what is art. In this instance there is no question as to the ‘moral’ character of the objects under consideration. They are denied admission, duty free, on the sole ground that they do not completely meet the requirements established by the existing law and court decisions for ‘works of art.’ The judgment of acknowledged experts is given no weight or consideration.

We believe the act of Congress which makes this situation possible must be amended.

Cubist Art fails to get past Customs [Feb. 22, 1936, NY Times]

UPDATE UPDATE Long and short of it, it’s not clear whether the 1916 ruling was really at issue, or whether it was the 1930 Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, which raised protectionist tariffs against wide swaths of imported goods, that contained the inadvertent language. But remarkably, the abstract art tariff discrimination continued for more than twenty years. There’s a NYT story from 1958 about Sen. Jacob Javits introducing legislation to modernize the language of the Customs art rule.

Basically, sculpture could be any material, but it had to depict “natural objects…in their true proportion of length, breadth and thickness,” which meant it tripped up African carvings, too. Painting could be anything, as long as it was “traditional materials,” which was ruled to exclude mosaic and collage or assemblage.

The Times reported that collector Donald Peters protested when his $450 1956 Alberto Burri collage was taxed 20% duty as “a manufacture of vegetable fibres” because “it had a background of burlap.” If it was “vegetable matter,” Peters argued, then it was only worth $1, “and the Government was entitled to 20 cents. Mr. Peters lost the argument.”

Which almost exactly mirrors the VAT shenanigans perpetrated by EU bureaucrats last year when they ruled that video artworks were actually electronic equipment, not art, and were thus subject to a higher VAT–but on the artwork’s price level, not the underlying hardware’s. And so it goes.

[Just as an aside, Sen. Javits: kind of a schlub? His wife? Smokin’. What was up with that?]

The excluded works:

Arp, Human Concretion

Giacometti, Standing Figure, Head-Landscape, Project for a city square,

Laurens, Bottle of Rum, Head, Guitar

Vantongerloo, Construction Within a Sphere, Construction of Volume Relations, Construction of Volume Relations [2]

Duchamp-Villon, The Lovers [2], The Horse

Gonzales, Head

Boccioni [misspelled as Doccioni], Development of a Bottle in Space, Continuity of Form in Space

Moore, Two Forms

Nicholson, Relief

Miro, Construction