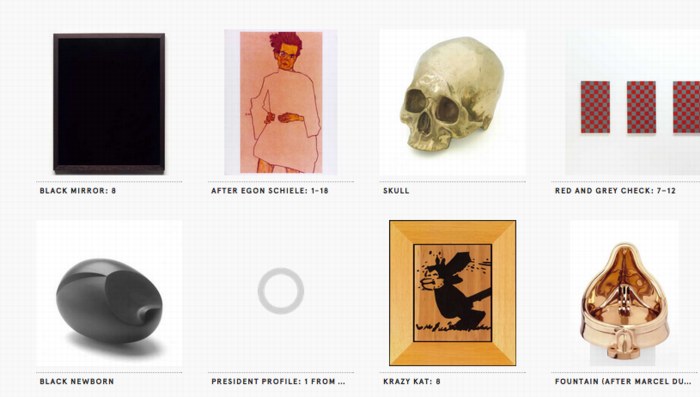

So Joshua Abelow posted this yesterday, Black Mirror, 2004, by Sherrie Levine. It was included in a group show that just closed at Joe Sheftel, Paint Hotel. But that doesn’t really shed any light on this particular work. Paint Hotel’s announcement opens with an Yves Alain Bois quote from Painting: The Task of Mourning and Joan Didion, and it

seeks to destabilize fixed theoretical and genealogical narratives. The point is not to be anti-theory, but rather to allow for an immediate experience.

Which, is part of my question. Because I can sure appreciate an immediate experience of Black Mirror; it’s an elegant, ambiguous object, a 16×20 black-painted sheet of glass in a sleek mahogany frame. As an autonomous object, it makes its own case. But of course, it didn’t just appear out of nowhere; it’s a Sherrie Levine, and we’re paying attention to it, or it’s entering this particular context, because it’s a Levine. And that’s what I wonder about. Why, and what?

installation view via paula cooper gallery

The readily available discussion of Black Mirror seems to be thin-to-nonexistent. There were originally twelve identical black mirrors exhibited at Paula Cooper in late 2004. The show was titled “Mourning Mirrors.” Here’s what we know:

Here, as with much of her sculpture, Levine’s interest lies foremost with the physical presence of the object and the sensual quality of the materials used. The mirrors’ dark gleam has the elegiac feel of funerary or memorial sculpture. With their frame and color, as well as their status as generic objects, the mirrors also maintain an ambiguous relationship to both monochromatic painting and the readymade.

For years, Levine’s work has raised critical questions about authenticity, the function of tradition and the relation of reproduction to original, questions central to artmaking today. Of her work, she says: “I try to make art which celebrates doubt and uncertainty. Which provokes answers but doesn’t give them. Which withholds absolute meaning by incorporating parasite meanings. Which suspends meaning while perpetually dispatching you toward interpretation, urging you beyond dogmatism, beyond doctrine, beyond ideology, beyond authority.”

So Levine’s interest here is in the physical presence of the generic object, which, sure, but the entire second paragraph feels unrelated, or unsupported by these objects.

I don’t mean to imply that I don’t like them; I do. And I like Richter’s mirrors and backpainted glass works, too. And any host of other artists who use mirrors and monochromes and readymades and paintings and originals and, just consider my buttons pushed. But I still don’t get it.

I mean, I guess Levine’s gotta make something. And she’s gotta show something. And this is what it is. But then we are looking at this thing because it’s a Levine, because of the brand, and the practice, and the history, not for the “generic object” itself. Let’s be real here. Paula showed this work because she believes in Levine and supports her in her practice, wherever it leads, and she trusts her.

just a few of the Levines at the Walker

And the Walker Art Center accepts Paula’s gift of a Black Mirror straight out of the show and into their collection because all of the above, plus they have made an institutional decision to collect Levine’s work in depth, including buying a bunch of work in 2002. So it’s a sign of a good relationship, if not a thank you, or a free gift with purchase.

Black Mirror makes the most sense to me in this context, of an artist’s work, over time, and the relationships and dialogues that form, and move from show to show and work to work.

And someone squeaked out a sale of a Black Mirror last year at Phillips for $60,000, a final bid of $48,000 against a too-hopeful estimate of $70-90,000, because, well, that’s a bit of a mystery to me. Phillips’ catalogue text is the only other text I’ve found online besides the “Mourning Mirrors” press release, which it quotes, and then muddles and contradicts completely:

The reflective surface exudes the elegiac severity of a funerary or memorial sculpture. The rich brown frame surrounding the sleek and cold glass lends the work the status of a generic object and maintains a relationship to both painting and the readymade.

…

Black Mirror: 4, 2004, appears disarmingly simple, yet there is something naughty lurking behind its smooth and lustrous surface. A mirror is intended to reflect the world around it; however, upon peering into Black Mirror: 4, 2004, a sense of mischief and secrecy pervades. The world appears not in its picture-perfect state, but doused in black ink, void of color, clarity, and precision. But instead of leaving its audience with a sense of impending doom, it is out of this precise bleakness that a gleeful mischief prevails.

Yes, gleeful mischief. Because what Debbie Downer’s gonna pay $90,000 for cold, funerary, generic, mournful, bleakness? This looks more like the auction house’s reflection than Levine’s.

Anyway, the point is, I love duality, and I kiss ambiguity’s feet. And I am always glad to be confounded and challenged to wrestle with contradictory notions in my head. But for some reason I’m really having trouble with Levine’s Black Mirror purporting to be a generic object when it’s really/also a branded good.