The question is not whether you can visit Walter De Maria’s Leaving Las Vegas; the question is, does it still exist?

Already in 1972 when discussing the land art project with Paul Cummings, Walter de Maria seemed to emphasize the difficulty of actually experiencing Las Vegas Piece as part of the actual experience of Las Vegas Piece. He’d graded a mile-long square onto a barren desert valley north of the city, and you’d have little chance of even finding it, much less seeing it, much less seeing it all:

it takes you about 2 or 3 hours to drive out to the valley and there is nothing in this valley except a cattle corral somewhere in the back of the valley. Then it takes you 20 minutes to walk off the road to get to the sculpture, so some people have missed it, have lost it. Then, when you hit this sculpture which is a mile long line cut with a bulldozer, at that point you have a choice of walking either east or west. If you walk east you hit a dead end; if you walk west you hit another road, at another point, you hit another line and you actually have a choice.

And on and on for several hours, until your choices and backtracking end in some combination of experiencing the entire sculpture on the ground; declaring victory or defeat partway through; and dying of exposure in the desert because you can’t find your car.

In a 2003 NYT interview, Virginia Dwan and Michael Kimmelman got a little myst-y eyed about being alone. They made Las Vegas Piece sound like an emotion machine that manipulates art world people into contemplating their solitude by losing themselves in the desert landscape. [It was also, De Maria acknowledged, a way to grab a viewer’s attention for hours, a whole day, not just the minutes or seconds it took to circle a sculpture in a gallery.]

In both those ways, Las Vegas Piece is still functioning perfectly, whether it actually exists or not. In 2008, the Center for Land Use Interpretation had listed Las Vegas Piece as “apparently, no longer visible.” And their map was uselessly vague.

But today, CLUI’s entry for the work has more information, if not more answers:

The piece is visible on online satellite maps, and there apparently are some discernable fragments of the lines on the ground.

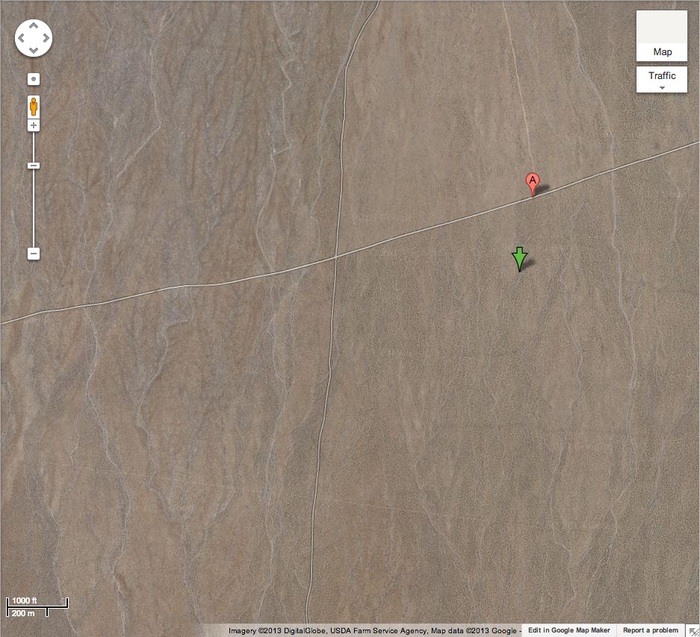

Yes, well. here is their latlong marker for Las Vegas Piece on Google Maps, [above] and I’ll be the first to admit I don’t see a thing. So I plugged the coordinates into the USGS’ database of historical satellite photographs and still came up empty. Maybe a better mapsearcher than I will find it.

And in early 2012, in the run-up to “Ends of The Earth,” her landmark land art show at MoCA, UCLA art historian Miwon Kwon engaged CLUI to lead her and her grad students on a road trip to visit Las Vegas Piece. UCLA Today reports that Kwon’s SUV had a blowout on the way:

Instead of giving up, they stuck it out. Eventually the first car did return, the expedition guide helped replace the tire, and Kwon was able to give her students an experience that, she hoped, would transform the way they thought about art and art history.

What was that experience, exactly? Was it just like the MOCA show itself, that of not seeing a De Maria? We who weren’t there will never know.

But check out CLUI’s own account from their Winter 2013 report, and I think we can read between the lines:

Some would argue that it isn’t there at all, that the piece is gone. Certainly, as originally intended by De Maria, the piece no longer exists, just as “none” of Heizer’s dry lake pieces exist, even if traces can be found. Of course these are ruins of land art, not land art. But for a group of art historians, the interest in going there was not to experience the piece, but to experience the place where the piece was. To understand it better forensically, and archeologically. And to ground truth the land art that usually exists to us only in photographs-to verify its historic existence heuristically.

Only the faintest sense of the lines of Las Vegas Piece is discernable, and barely so enough to leave some unconvinced that they saw it at all-its existence is a matter of interpretation. It’s on the limits of perception, conjured up in the mind’s eye and space by lining up mountain ranges in the background of photographs in art history books with those in the distance of the actual site. In a paralaxed overlay, when the alignment lines up, the viewer descends into the photo at the same time the piece in the photo emerges into the viewer’s live view. You are there, even if it is not.

Yes, well. To the extent archeological interpretation and three SUVs full of grad students excitedly pacing off every bald spot in the desert has supplanted the evocation of existential solitude and man’s lonely movement through time, then yes, Las Vegas Piece no longer exists. This is an important takeaway for land art pilgrims whether they’re in Kwon’s seminar or not.

But it still makes me wonder what De Maria was actually intending for his work. He rejected the gallery rendition, the groundlevel photodocumentation, and the all-seeing satellite/aerial photograph. But how did the people who went to see it actually find it? Did he tell them? Did he give them elaborate directions? Did he draw them a map? Did he plot it on a map? Did he give people bad directions just for fun? Does it matter if he actually ever bulldozed it in the first place? Why would we be inclined to want to walk exactly along De Maria’s paths, but not, say, Richard Long’s?

And if we’re going to be in an archaeological mode, why not just use lidar to pinpoint the exact location? But the more interesting question, I think, is what’s stopping someone from just driving a bulldozer out across the desert one morning and redrawing it? Just do it, stick it out there somewhere in the general area, and let someone MFA stumble across it after the next Google Earth update?