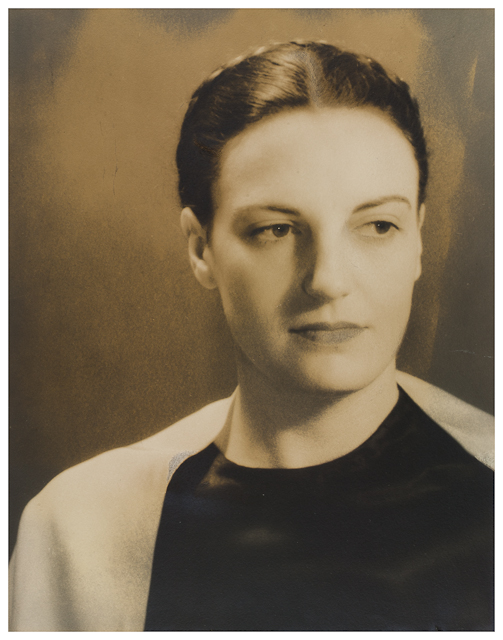

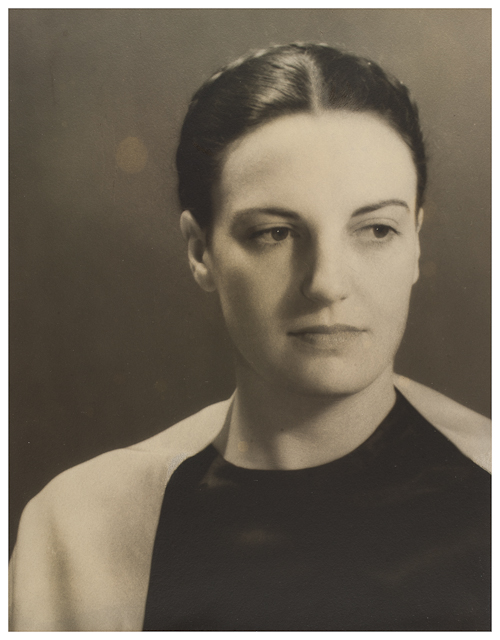

So like twelve years ago, I stumbled across this photo in some dealer’s bin. It’s a portrait of a young woman with hair pulled back, a braid just peeking out across the back of her head, and she’s wearing a very plain, even severe outfit. There’s a great rhythm of contrasts between the sitter’s hair and forehead, her cheeks, and her dress and shawl.

On the back was written “photograph by Berenice Abbott, N.Y.,” in one hand [but not the signature Abbott’s known for], and in another,

Mrs Joseph Barber

2 col cut

Sun Soc

EBL

Which meant this was Mrs Barber’s engagement photo? Pretty modern. And it was a print submitted to a newspaper with a wedding announcement, where it ended up in a morgue for decades.

So I bought the print, and figured I could sleuth it out and authenticate it. Abbott would have been a bold choice for a wedding portrait in 1935-6. Most Abbott portraits we’ve seen are of sitters we know: in Paris she famously photographed James Joyce and Eugene Atget, for example.

Mrs. Barber was not, for example, included in the portrait portfolios Abbott published at various times; she’s not one of the 42 portraits on the website of Commerce Graphics, the outfit which acquired Abbott’s archive. Of course, they didn’t have a website when I got the photo. Google Images had barely launched, and still kind of sucked, in fact. So the only way to research was through books, where Mrs. Barber didn’t appear, or through newspaper archives, where, eventually, she did.

Joseph Barber Jr., of Andover, Harvard, and Columbia Journalism School, was an editor at The Atlantic Monthly when he married Eileen Paradis, a graduate of Mt Holyoke College and the University of Grenoble, on 15 February 1936. He would later become the magazine’s managing editor and hold editing and reporting positions at the Washington Post. A collection of Barber’s reports for The Atlantic was published in 1941 as a book, Hawaii: Restless Rampart. In it, he maps out the monopolistic plantation feudalism of the island territory’s politics, as well as the massive US military buildup of the book’s title. He quoted an army official as saying, “We intend to make the price of taking Pearl Harbor so prohibitively high that no enemy would want to pay it.”

Anyway, Eileen Paradis. The only mention I could find of Paradis at the time was her wedding announcement in a Boston paper [on microfiche!], where she was reported to have worn “an oyster white chiffon gown made on Grecian lines,” with a matching veil held by a gold wreath, and a gold belt. Which sounds like it’d match the hair. But the photo in the Globe that day was for Miss Mary Redmond Davidson, who had announced her engagement to Mr. Samuel Loring Ayres, Jr.

And that’s where it stood. A dead end, confirming Paradis/Barber’s marriage, but no proof of whether the photo was actually her, and, of course, whether Abbott had taken it. I didn’t have a hallway packed salon-style with vintage photographs, and I’m not really into hanging lone pictures of other peoples’ relatives, so I put it away.

And I just found it this morning while looking for some documentation of another work. On a whim, I typed “Eileen Paradis” back into Google, and whaddyaknow. Amid all the citations from the alumni newsletters and the Harvard Club directories is a collection of silver and art donated to the Mt. Holyoke College Museum of Art by The Estate of Eileen Paradis Barber (Class of 1929) in 1997.

The Barbers turned out to collect a fair amount of modern art in their day. There were watercolors by Arthur Dove, works by Max Ernst, Isamu Noguchi, Reginald Marsh, Romare Bearden, and John Marin, along with a sheaf of Japanese woodblocks and a couple of impressionist drawings. There were also five photographs, all by Berenice Abbott: three classic images from her Changing New York project–and two prints of Paradis’ portrait.

Berenice Abbott, Eileen Barber, prob. 1936, MH 1997.14.4

One print is much lighter, and the background especially looks to have been dodged or retouched. The other is closer to mine, though the image is a little longer. From the jpg, at least, the image looks like the best of the three, which may be why Barber kept it.

Berenice Abbott, Eileen Barber, prob. 1936, MH 1997.14.4a

Mine also has a handling crease on the far left edge and the top left corner, and a little orange spot in the image that looks like a chemical burn, which may be why she sent it to the paper.

So mystery solved. I’m kind of marveling at how something once impossible became instantly knowable. It still feels like magic sometimes around here. I’m also kind of daunted, because I found out this photograph, this piece of paper I’d bought on a hunch, turns out to be what I thought it was. Abbott’s famous images are everywhere, and published in editions of hundreds. But this is one of only three known to exist. and what series of happy accidents kept it intact this long?

update: After I published this a scholar familiar with Abbott’s work confirmed that Barber’s portrait does indeed reside in the artist’s archive, among many other interesting portraits of less public figures.

And it was suggested that the Barbers got to know Abbott via the writer Elizabeth McCausland. McCausland wrote about art for many publications of the day, and on many of the artists in the Barbers’ collection. And of course, McCausland was also Abbott’s partner and frequent collaborator, writing the texts and captions for her photobooks and exhibitions.

So rather than just an avant-garde wedding portrait commission, the photo is likely a document of a friendship and a community of artists and writers.